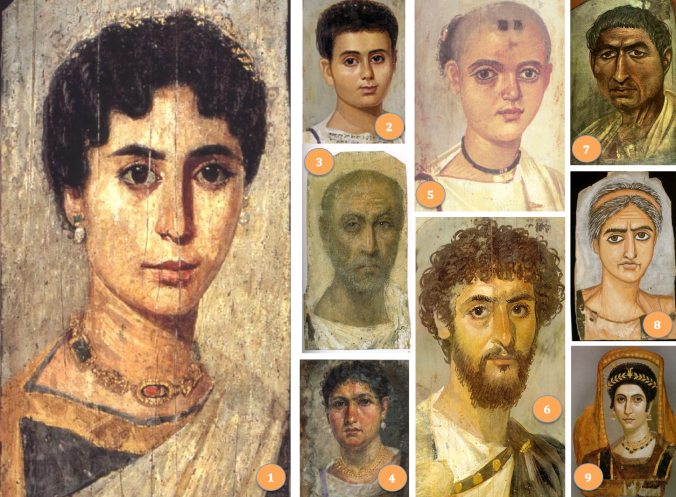

Some Fayum portraits, dating collectively to the period AD 70-250. The numbers refer to discussions in the text.

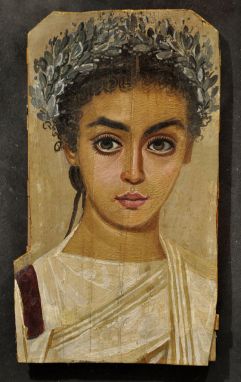

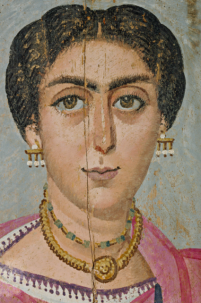

She is very beautiful. Her face is flawless: long and olive skinned, the nose long too, but neat and narrow, the brows crafted, the chin just firm enough to suggest a certain liveliness of character. She has dark hair, and one gets the distinct impression that it has potential for unruliness, but it has been called to order and fashionably styled, cut short over the ears in order to display expensive jewellery. A half-smile plays about her lips, and it does not seem too much to read a hint of amusement into her large brown eyes. It is easy to imagine meeting her at some elegant affair, for she seems alive – yet she is dead, and has been dead for rather more than 1,800 years [1].

There is something profoundly disconcerting about gazing into the face of someone who lived so long ago, and have them look straight back at you – long and level, quizzical – in a way that simulates direct connection. The unease we feel is only magnified when the circumstances are unusual, as they are in the case of our elegant brunette, for we are simply not used to seeing such realistic portrayals of human faces from such a distant period. Old Masters may have captured character this well during the 1600s, but our portrait dates to Roman-era Egypt in around 190 AD, and is separated from modern schools of portraiture by well over a thousand year’s worth of stylised iconography and crude medieval sketches. Add to this the sheer directness of the painting (which is quite devoid of background, indeed absent anything that might compete for our attention with those compelling eyes), and the grip that the image has on us is easier to understand.

The picture comes from the Fayum oasis, a wealthy district on the left bank of the Nile about 65 miles south of Cairo. It was dug up from a graveyard there more than a century ago, and is one of about a thousand such images, dating from around the time of Christ until 300 AD or later, that have survived long years underground and now lie scattered among the collections of the world’s great museums. Collectively, they are usually known as “Fayum paintings,” or sometimes “Fayum mummy portraits,” for most of them were recovered wrapped up in the burial linens of ancient mummies, placed in the spot where the face would once have been. They are the oldest painted portraits to have survived from anywhere in the world.

The paintings are the products of a multicultural society, one in which Romans mixed with native Egyptians and with Greeks descended from the Macedonian armies of Alexander the Great to create a polyglot community. The vast majority come from two sites south of the oasis, er-Rubayat (the necropolis of ancient Philadelphia) and Hawara (associated in Roman times with Arsinoe); they combine the religious imagery of Rome and Egypt, and production of them seems to have ceased shortly before the final Christianisation of the Roman Empire. Each painting shows the head and shoulders of a man, woman or child and is painted on a sliver of wood measuring around 12 inches by 6 [30 by 15cm]. The portraits are, therefore, very nearly life-sized.

Fayum paintings have been celebrated for more than a century for the vividness and immediacy of the connection that they seem to establish between modern viewers and long-dead Egyptians. “They tempt us to imagine,” the archaeologist John Prag remarks, “that we can literally and figuratively come face to face with the past.” For John Berger, “the Fayum portraits touch us as if they had been painted last month.” And, reviewing an exhibition of portraits held at the Metropolitan Museum in New York at the turn of the century, Holland Cotter of the New York Times detected a whole gamut of human emotions in them – “despair, bafflement, anger” – and likened visiting the show to “attending a party among friends.”

“The faces certainly seem familiar,” Cotter wrote.

“The prettiest girl from high school is here, and that smug 10-to-6’er she married. So is a distant, distant cousin, and a barely remembered college chum, and even an old flame you’d prefer to forget.

“And there are strangers who aren’t really strangers. Didn’t you see that elderly gent in the subway and brush past that unisex youth in the street? And who is that woman across the room with the emerald necklace and stricken face? An Anne or an Alice, she looks overwhelmed. By what? You should go over and talk to her, but she’s off in a world of her own.”

The Fayum oasis, showing the areas where the mummy portraits were found. From Roberts. Click to view in higher resolution.

It is worth pausing here to consider in a little more detail exactly why the Fayum paintings have the effect on us they do. It is certainly true, as Cotter says, that they appear to capture personality as well as mere appearance. Stripped of their funereal context, moreover, they are naturalistic, indeed in important respects modernist in style, and this (as Christina Riggs astutely points out) helps them to appeal to today’s Western sensibilities. They lack the pomposity that one sometimes finds in formal portraiture, and their large, dark eyes recall popular kitsch styles. They have an indefinably familiar look.

But there is more to the mummy portraits than that. They are, for one thing, soulful, in a literal as well as a colloquial sense, for these are images that were specifically designed to accompany their owners into the afterlife. And, most importantly of all, they look right at us while we’re viewing them. With the exception of a handful of rough near-caricatures [8] – which seem more likely to be cheaply-commissioned images of faithful servants than the products of particularly unskilled artists – every known mummy portrait, whether pictured head-on or in three-quarters perspective, gives the impression of inviting conversation.

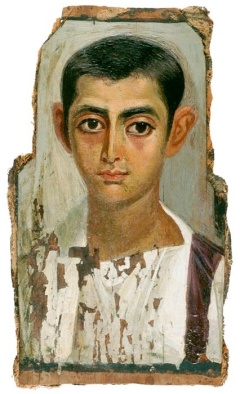

It is very easy to read stories into many of the paintings. Among the most moving of the mummy portraits is one showing the face of a boy who died young, aged perhaps around 10, sometime late in the second century. His head has been almost completely shaved, leaving only two small, square tufts atop his forehead, and he wears a black necklace from which hangs the sort of container in which amulets protecting from the evil eye were placed [5]. Salima Ikram suggests that this unique hairstyle is evidence that the boy had been desperately ill for quite some time – long enough for his frantic parents to have his hair ritually shorn at a local shrine in an attempt to please some deity. “If the child was cured,” Ikram sums up the local customs of the time, “the tufts would be shaved off at the shrine amidst a celebration, and the hair buried… loose, or enclosed in a clay ball.”

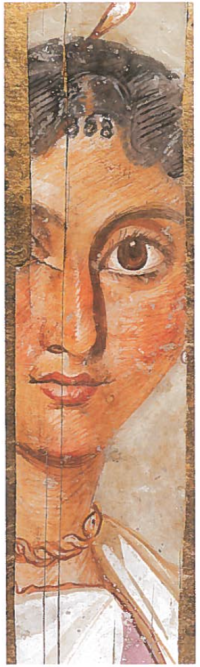

Another evocative Fayum image, much more stylised this time, is this fragment of a larger painting which has snapped in two and now gives the impression that the sitter is peeking out at us from behind a screen.

Seen from this perspective, it is easy to guess that the strange potpourri of symbols that are so prominent in the young boy’s portrait were the result of a desperate case, long protracted, in which a much-loved child slowly declined and became mortally ill before his parents’ eyes. It is surely likely, Ikram notes, that in such circumstances a family would use “all varieties of medical and religious cures available to them, regardless of whether they were Greek, Roman or Egyptian.” The tragedy, of course, is that these efforts at a cure all failed, for this was a boy who died.

The Fayum mummy paintings have been known for quite some time. They were never really hidden, merely buried – along with the men, women and children they depicted – in rough coffins in ordinary cemeteries. Some must have been dug up well over a thousand years ago, but the earliest discovery of Fayum portraits that we have record of dates only to 1616, when the Italian traveller Pietro della Valle (1586-1642) visited Egypt on his way to India. Della Valle passed through Saqqara – a vast necropolis, filled with the crumbling remains of ancient pyramids, which had once been the main burial ground for the people of Memphis – and there was offered two mummies, each adorned with a lifelike painting of the man inside the ancient linen wrappings.

Whether della Valle’s mummies had been brought up from Fayum or were uncovered in Saqqara (and thus represent an otherwise unknown cache of paintings) is now impossible to say – but, almost miraculously, these early traveller’s souvenirs survived their owner’s years of wandering through Palestine and southern India, and returned with him to Italy in 1626. Della Valle later published a description of them, complete with engravings of the portraits, but his work was treated as a curiosity. Reading between the lines of his account, it seems likely that the paintings arrived in Italy in pretty poor condition – dirty, crusted with sand, and largely lacking the lustre of the restored paintings that are so striking today. Probably that explains the indifferent quality of the engravings, and the almost complete lack of interest displayed in Italy in the portraits themselves.

Whatever the reason for this neglect, it was not until early in the 19th century that any significant quantity of mummy portraits were gathered together. The collector in this case was Henry Salt, a noted explorer who was then the British consul in Egypt. Salt assembled a group of portraits – from sources that remain obscure – that eventually found their way into the Louvre in Paris, and he was followed a few decades later by a Vienna merchant and collector by the name of Theodor Graf. Graf was fortunate enough to visit Egypt in 1887, just after an ancient graveyard had been uncovered and enthusiastically plundered in Fayum. A large number of the bodies recovered from this cemetery turned out to have been buried complete with mummy portraits, and Graf was able to assemble several dozen examples – stripped, sadly, of both their context and their provenance – by trawling through Cairo’s shady art markets.

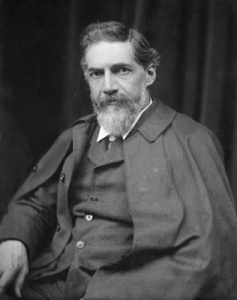

William Flinders Petrie, one of the fathers of modern archaeology, made two visits to Fayum. His careful excavation records supply most of the information we have about how the mummy portraits were discovered.

This time the portraits were in good condition, and they aroused intense interest everywhere. It was not long before their true source was revealed; the pioneer British archaeologist William Flinders Petrie, who came to the the oasis early in 1888 in search of something else entirely – traces of a lost labyrinth, supposedly associated with the pyramid of Amenemhet III (c.1800 BC), and described by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus as containing no fewer than 3,000 rooms – uncovered several groups of graves containing Fayum paintings. Unlike Graf, he kept good notes, and did what he could to conserve the paintings that his men recovered, even when they were in atrocious condition. Many of his finds have since been restored using modern techniques.

Judging from Petrie’s excavation records – the only ones of any value from this period – most of the portraits were excavated from shallow brick pits in abandoned cemeteries. In a few cases mummies were found encased in basic wood coffins, but for the most part they were discovered “huddled away… irregularly in any sort of hole… lumped together.” It has been suggested that the mummies, and the portraits, were probably placed in a family mausoleum at first, and visited regularly for religious ceremonies, being finally buried only several generations later, when all the immediate family were dead. That might explain why most of these expensive mummies have been roughly treated; in some cases a cloth had been laid loosely over the portrait, but many were directly exposed to the scouring of the Egyptian sands, and it seems almost a miracle that the fragile images they bore survived nearly two millennia in their graves.

Certainly the portraits are delicate. Those found in Philadelphia were typically executed in tempera – that is, using egg whites to produce a finish resembling watercolour. Those that come from Arsinoe are more sophisticated, being painted in encaustic – a technique that involves mixing pigments with soft wax, applying it to slivers of sycamore tree or lime, and sealing the image with heat to produce results that resemble oil paintings.

One of the few Fayum portraits to bear a name is this fragment identifying it – in Greek – as “Sarapi.” She would have been a devotee of Sarapis, a Graceco-Egyptian god whose cult had been heavily promoted during the Ptolemaic period (323-30 BC).

Understanding how the Fayum images were made, however, tells us little about exactly when they were painted – or, much more controversially, why. It is to those questions that we now turn, with the observation that the answers tell us almost as much about ourselves as they do about the Egypt of the first and second centuries AD.

Resolving the problem of when the mummy portraits were produced requires a good deal of research and not a little faith. We know so little of the histories of Philadelphia or Arsinoe that it is rare for Fayum paintings to be datable by their physical context alone, although one group found further south, at Antinoopolis, can be assumed to date to no earlier than 130, since the Emperor Hadrian founded the city in that year. Other than that, though, little is certain, and much of the dating that has been done involves reconciling the testimony of contradictory internal indicators, principally the evidence of fashion, styles of jewellery and of palaeography – the study of handwriting. It has been argued, for example, that portraits showing bearded men can also be dated to no earlier than Hadrian’s day, since it was he who reintroduced the style for beards after centuries of clean shaving in Rome. But contemporary statuary tells us that Greeks never entirely abandoned the fashion for facial hair, and in a multicultural society like early Christian era Fayum, that fact alone is sufficient to muddy waters.

Much attention, similarly, has been devoted to the fashion choices of the subjects of the mummy portraits, and especially their hairstyles. Many of the older women in the portraits, for instance, wear their hair high, piled up and secured with a large pin, a fashion very characteristic of the Flavian age (69-96 AD). And many of the youths are clad simply in white, a style closely associated with the temples of the day [2]. Enough is known from other sources of the march of fashion in the ancient world for this sort of dating to yield plausible answers to a number of mysteries.

Still, it is well worth noting that such results can still be unreliable. We don’t know, for example, whether styles changed more slowly, or were clung onto for longer, in a backwater like Fayum than in Rome. And when an alternative dating method can be brought to bear, the results are more confusing than comforting. Riggs cites a case in which a female portrait was confidently dated, from its hairstyle, to the reign of the emperor Septimus Severus (193-211), only for palaeography to date the same portrait to about a hundred years earlier, and a study of the subject’s jewellery to suggest that it was painted almost two full centuries before Severus’s reign.

That’s enough to suggest to me that any attempts to date specific Fayum portraits should be viewed with caution. One or two scholars have placed their first occurrence at about 150 BC; others have suggested that the last may have been produced as late as some time in the 400s. Sticking with the general consensus, it is difficult to do more than conclude that most were probably painted in the period 50 to 250 AD – but even that implies that some at least were probably contemporary with the writing of the gospels and the deposit of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

This mummy portrait – like many others – shows signs of having been cut down from its original size in order to fit its casing. One group of archaeologists has used this evidence to argue that the paintings were made from life, and only later adapted to funerary purposes.

If we ask why the Fayum paintings were produced, though, we begin to encounter problems – puzzles that go to the heart of what the images were meant for and what they really show. These questions have sparked several important disputes, for there is almost no scholarly consensus as to whether the portraits were primarily intended to be shown in the home, or were funerary objects designed to be displayed only in a mausoleum. Without knowing the answer to that problem, it is hard to know whether these images were painted when their subjects were alive or dead – even whether they are really pictures of individuals at all.

To begin with what we do know, or can reasonably deduce, it seems almost certain that mummy portraits – or at least the burials of mummy portraits – were a product of beliefs about the afterlife. Every Egyptian was thought to have a ka and ba, which survived death and continued to thrive so long as they could reunite periodically with their bodily remains; it was for this reason that so much time, money and effort was poured into the creation of elaborate mummies. The ka (or, very broadly, life force) resided either in a mummy or in some image of a dead person – for the really rich, typically a statue. The ba, meanwhile (depicted in tomb paintings as a bird, and roughly equivalent to ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’), could leave the body to find food and drink, but had to return to its tomb each night with the nourishment needed by the ka.

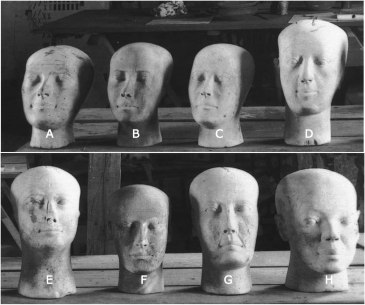

Since it was vital the ka and ba could be reunited in their mummy, it was also important to Egyptians that mummies could be readily identified. Written names would often be attached to them, and a handful of tombs dating to the Old Kingdom (c.2700-2200 BC) contain objects known as false or “reserve” heads – three dimensional head-and-neck models of apparently real people, which seem to have been designed to stand on the floor of the burial chamber. It seems plausible that both false heads and Fayum paintings were meant to aid in the identification of the deceased, and help the ka and ba to quickly relocate their mummies. They might also have been intended to provide a proxy that would allow to ka to survive if its mummy was destroyed.

A group of false heads from Old Kingdom tombs, excavated in 1913. They seem to have served much the same purpose as the Fayum paintings, produced 2,500 years later.

It is also possible to make a second statement: that the Fayum paintings are not images of everyday Egyptians, as they are often thought to be. The people that they depict could afford fine clothes and jewellery; one Fayum woman, David L. Thompson notes, wears a golden wreath and three expensive necklaces set with gems – “an orgy of gold and emeralds.” [9] When they died, their lives were celebrated with elaborate funerals and concluded in the time-consuming, costly process of mummification. These were not luxuries available to every man, woman and child in Roman Egypt. The paintings depict members of an elite.

As to the question of whether or not the subjects of the paintings sat for their own portraits – that is much more difficult to answer. At first glance it does not appear unlikely, given the high quality of much of the work and the sheer vivacity of the portrayals. A few subjects, such as the shaven-headed boy, were plainly ill when they were painted, but for the most part the men and women in these pictures look healthy – indeed, in the prime of life.

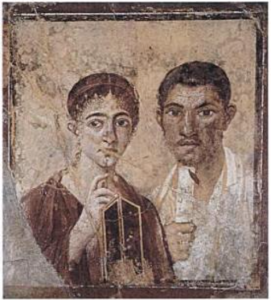

A wall painting from the house of Terrentius Neo, entombed during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. Its focus on head-and-shoulders portraiture and its use of perspective are both reminiscent of the Fayum paintings.

We know, too, that portrait paintings could be found in many Roman households in this era. Pliny the Elder wrote that “realistic portraiture… has for many generations been the highest ambition of art,” and family pictures dating to the same period as the Fayum images have been uncovered during excavations at Pompeii. Such portraits were probably affordable even to moderately wealthy Romans; a scrap of papyrus – found in Egypt but written at Misenum, in the Bay of Naples, some time in the second century – bears a note written by a sailor by the name of Apion, informing his father that he is sending a small picture of himself back home.

A second argument in favour of the idea that the paintings were drawn from life lies in the shape and form of the examples that survive. Images that were, it seems, originally painted as straightforward rectangles have been hacked and cut to fit them to a mummy’s shape [8, 9]. If they were not originally intended as household portraits, the logic runs, why not paint them the right shape and size in the first place?

Yet there are also scraps of evidence hinting that the paintings show their subjects as they looked, not in the prime of life, but at the moment of their death. Facial reconstructions attempted a few years ago on the skulls of two mummies associated with specific Fayum paintings produced images that very closely match the faces of the dead. That suggests that these portraits were sketched around the time of death, not drawn to take their place on some family mantlepiece years earlier.

![One of a pair of Fayum paintings which remain attached to their original mummies. The other [right] shows a woman who died young, sometime in her early 20s.](https://mikedashhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/fayum-reconstruction-11.png?w=676&h=414)

One of a pair of Fayum paintings which remain attached to their original mummies. A reconstruction of the mummy’s face (right) suggests the essential accuracy of the portrait – and implies that it was painted at around the time of the man’s death.

Many Fayum paintings – like this portrait of a girl dated to roughly 120-150 AD – feature subjects with abnormally large eyes. Are these paintings examples of Roman-era kitsch, the products of artists of limited talent – or a deliberate feature with religious overtones?

Let us assume, then, for a moment that the Fayum paintings are not what they appear to be – that they are not portraits drawn from life. The implications of this thought experiment are startling. Would it matter quite so much if images intended for interment were not entirely realistic? And, if the paintings can be seen as part of the rituals of death, might that explain why they contain such strong symbolic elements?

Consider, for example, the almost cartoonish prominence of the eyes found in these paintings. There are many mummy portraits in which an otherwise natural-looking face has been distorted out of recognition by the need to accommodate such eyes. If only one of two examples of this trait existed, it might be possible to explain them as the work of poor artists unskilled in perspective. The truth, however, is that this feature can be found in almost every mummy portrait. Might this suggest the largeness of the subjects’ eyes reflects the ideas of the time? Ancient Egyptians believed that eyes were windows on the soul, so it is no surprise (so Thompson says) that we find them “emphasised, and even exaggerated, since… the mummy was thought to be [the soul’s] permanent abode.”

It is for these reasons that Christina Riggs insists that we delude ourselves in reading character or beauty into mummy portraits. “Feeling empathy for long-dead individuals says more about ourselves than it does about the ancient society or individual in question,” she writes. And John Prag takes things one distressing step further by suggesting that the Fayum images were most likely the products of “something approaching a production line, in which each painter quite naturally built up his own formulae and his own tricks.” Those ‘tricks,’ he concludes, included creating a recognisable group of basic facial shapes that could be modified quite easily. Such models could be easily deployed when a new commission was received, then modified to create distinctive individual “looks” by the addition of beards or hairstyles.

One of a pair of paintings dating to around 190 AD which John Prag believes suggest that the faces in the mummy portraits are variations on a set of basic types and shapes…

It seems a dispiriting idea. If Prag is right, then the distinctive traits that make the mummy portraits memorable are in the end “simply the quirks of a workshop or painter,” and the antique Egyptians who gaze out as us from Fayum portraits are not real people at all. They are merely avatars – representations of something real that are not real in themselves.

It’s possible that this is true, and Prag is undeniably correct to draw attention to the similarities between the faces in some of the mummy portraits. But there is an alternative explanation, which has been advanced by other archaeologists, and that is that some paintings show close relatives. Perhaps the two women whom Prag sees as the product of a harried, unimaginative artist’s brush are really mother and daughter.

It bears considerable similarities to a second painting, also dated to c.190 AD. The earrings are different and the mouth is wider – but do the similarities in hair, eyebrows and facial structure suggest a family relationship, or the output of an ancient production line?

And perhaps the curious resemblance between the brunette on whose beauty we reflected at the beginning of this post and a young, bearded man who has the same sort of eyebrows and the same sort of nose, and whose portrait was dug up from the same graveyard in Philadelphia, exists merely because they once were brother and sister. [1&6]

My thanks to Joanne Backhouse of the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, for drawing my attention to the phenomenon of false heads.

Sources

Holland Cotter. “Expressions so ancient, yet familiar.” New York Times, 18 February 2000; C.C. Edgar. “On the dating of the Fayum portraits.” In The Journal of Hellenic Studies 25 (1905); Suzanna M.Grant. “Two ‘Fayum’ portaits.” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 72 (1978); Salima Ikram. “Barbering the beardless: a possible explanation for the tufted hairstyle depicted in the ‘Fayum’ portrait of a young boy.” In The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 89 (2003); Dominic Montserrat. “The representation of young males in ‘Fayum portraits’.” In The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79 (1993); A.J.N.W. Prag. “Proportion and personality in the Fayum Portraits.” British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 3 (2002); Christina Riggs. “Facing the dead: recent research on the funerary art of Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt.” In American Journal of Archaeology 106 (2002); Paul Roberts. Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. London: the British Museum Press, 2008; David L. Thompson. “Four ‘Fayum Portraits’ in the Getty Museum.” In The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 2 (1975); David L. Thompson. Mummy Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1982; Susan Walker (ed.) Ancient Faces. Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. New York: Routledge, 2000; John Wortley. “The origins of Christian veneration of body parts.” In Revue de l’Histoire des Religions 233 (2006).

Reblogged this on galesmind and commented:

Fascinating article and the faces haunt you.

This was a really interesting article. Thanks for sharing it with me.

j

Pingback: The Fayum mummy portraits

Interesting, thanks!

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

I love love love reading your stuff. Great piece as always. Sharing!

Thank you for your kind words. It’s great to be back at work, and I have a couple of pieces on mysteries coming up next month that I hope will interest you.

Reblogged this on Tome and Tomb.

It does look like work from the 1800’s! This was the neoclassical mission, to reignite the Greco-Roman aesthetic. The problem is, many Greek and Roman-era works were destroyed by the iconoclasts (much like ISIL today). The better the work was, the faster it was destroyed. So we don’t really know what the best looked like. But, based on these portraits, we can imagine it was fantastic.

The level of detail and scale is absolutely amazing. The face is so lifelike looking and reminds me of the level of accuracy found during the later middle ages portraits.

I always thought ancient artists were more than capable of making realistic art, but they rarely did because stylized art was so in-demand.

That’s what gets me. The realism on display here is stunning. Fast forward several hundred years and it almost seems to be gone, not to return for quite a while.

The most fun part of all of this, for me, is that these portraits have done exactly what they set out to do. Some part of these folks now live on eternally as we share these images. If they only knew…

Exactly. Even though their names may have been forgotten (I’m not sure if there was a name on the sarcophagus) people will know what they look like even thousands of years after their deaths. In a way they have been granted the immortality that they wanted after death.

One of the examples at the Metropolitan Museum of Art shows incredible detail, including a scar from an eye surgery. It’s so interesting to see ancient Egyptians portrayed realistically without much stylization or idealization.

Pingback: Ancient places, modern faces; the Fayum panel portraits | James Mulraine

I am of the opinion (haven’t seen this expressed elsewhere) that those wealthy enough to have burials like this may often have had their portraits painted BEFORE they died, when young, to depict them at their “best”. I’ve never seen a Fayum portrait of an elderly person, but surely SOME of these people must have made it to old age. We see a similar thing today in newspapers, where people die in their 80’s or 90’s, but the photos of them published were taken 30 to 50 years prior.

Pingback: Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: City of the Sharp-Nosed… | PAIDES

[…] There is a fanastic essay on these portraits on a site called “Blast from the Past” by Mike Dash. Really well written and researched essays on all kinds of interesting and obscure historical topics. Be warned, you will lose days reading them all […]

[…] Thank you just my kind of thing! […]

A great read. Thanks!

[…] To find out more about the Fayum Mummy Portraits, this is a fabulous #longread from Historian Mike Dash about their significance and meaning […]

I was recently introduced to Fayum portraits, and my interest (and a google search) brought me here. Thank you! What a fascinating and well researched essay. I look forward to reading more of your entries on other historical topics.

Pingback: Fayum mummy portraits: the earliest painted portraits – That's How The Light Gets In

[…] Have you ever wondered what some of those mummified ancient Egyptians looked like in real-life? Mike Dash has a fantastic piece about just that. And it’s filled with really spectacular pictures. Check it out! […]

Real people from Ancient Egypt – a fascinating article.

These portraits always remind me that the ancient Egyptians were real people. Sometimes, even Egyptologists need reminding…

Kara, thank you for the link to a fabulous, interesting, informative article. I’ve been fascinated by mummy portraits since I first saw them at the ‘original’ Getty villa years ago.

#6. Fayum hipster before it was, um, popular.

These are very late egyptian portraits.. of the age after the Roman conquest. They are too similar to Roman portraits, even in their hairstyle, jewels and clothes.

Too similar for…?

For being “original” egyptian portraits, belonging to the age of true Pharaohs, when Egypt was a vast kingdom and a free land and had art, picture and sculputre of its own. Foreign influences are far too plain to see here.

reading the article is a good thing

Lets remember these people are mainly Greeks and Romans; the ruling class of the time … look at those noses!

They look like greeks to me

They look just like Egyptians today. Looking at them I feel I have met some of these people.

Nothing like real Egyptians(kemites) they look Greek or Roman

They sure didn’t smile much for their portraits did they. They look mostly Caucasian. ?

You people saying these are not really Egyptians just because they are from the Roman period are misinformed. These fayum portraits have Roman style realism instead of stylized Egyptian art but that doesn’t mean they are not Egyptian. Tests have shown that the mummies who these portraits are of have more biologically in common with ancient Egyptians from dynasties previous than they have any other ethnicity. A mesh of cultures is what these paintings represent; Egyptian’s still using mummification but with a touch of greco-roman style. The majority of the fayum portraits ARE indigenous Egyptians, it’s believed only 30% of Fayium was Greek! Egyptians took on alot of the roman culture and that’s what were seeing here in the portraits for the most part.

“Under Greco-Roman rule, Egypt hosted several Greek settlements, mostly concentrated in Alexandria, but also in a few other cities, where Greek settlers lived alongside some seven to ten million native Egyptians. Native Egyptians also came to settle in Faiyum from all over the country, notably the Nile Delta, Upper Egypt, Oxyrhynchus and Memphis, to undertake the labor involved in the land reclamation process, as attested by personal names, local cults and recovered papyri.

While some try to claim that the Fayum portraits represent Greek settlers in Egypt, that is incorrect. The Faiyum portraits instead reflect the complex synthesis of the predominant Egyptian culture and that of the elite Greek MINORITY in the city.

The dental morphology of the Roman-period Faiyum mummies was compared with that of earlier Egyptian populations, and was found to be “much more closely akin” to that of ancient Egyptians than to Greeks or other European populations.

It is estimated that 30 percent of the population of Faiyum was Greek during the Ptolemaic period, with the rest being native Egyptians. By the Roman period, much of the “Greek” population of Faiyum was made-up of either Hellenized Egyptians (Egyptians who took on Greek/Roman culture) or people of mixed Egyptian-Greek origins. The Fayum portraits are a wonderful glimpse into the faces of Egypt’s past.”

They would have had the skin tones of modern Mediterranean peoples.

It isn’t misinformed. The Greeks were not minorities in the area. Yes, the ruling elite was Greek, but there was also a large Greek community in the area by the time of Roman rule. There had already been centuries of emigration from the Mediterranean by this time. The area was Hellenistic when this artistic funerary tradition was dominant. There was a strong Greco-Roman presence in the Fayum and all the surrounding areas of Egypt for centuries before and after the Romans took control. Alexander the Great chose the site for the building of his capital city Alexandria, and the Greek Ptolemaic empire which succeeded him adapted Egyptian customs to create a unique Greco-Egyptian civilization which encompassed Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and Jews. Of course some of the DNA will belong to Egyptians, they were a huge part of the life in the area at this time. The portraits are one of many manifestations of the hybridization of cultures that had been an active policy of both the native Egyptian priesthood and the Greco-Roman rulers since the days of Alexander.

I think saying misinformed isn’t wrong when some early commenters were suggesting the fayum portraits are total foreigners to Egypt and that the true Egyptians were a totally different race of people, which is false. And 30% referred to the settlers in the location of Fayium, not the whole of Egypt.

Anyway, Anthony (nice name!🦁) You pretty much said much of what I said in a way more informative, better way. I did say that these portraits show the mixture of cultures. Many Egyptians were hellenised (indigenous people taking on GrecoRoman culture and customs), some interbred, and not forgetting, many of the Greeks/Romans took on Egyptian religion too, with a GrecoRoman twist. These mummies are a great example of the merging of cultures, mummification; an Egyptian religious tradition still took place, but with Greco Roman realism style portraits.

Only 900 mummy portraits have been found and if the mummies of these portraits that were tested have more biologically in common with Egyptians of the past then they do with Greeks, Romans or any other country nearby Egypt, that goes against the notion you see in the comments; that the fayum mummies are simply foreigners.

The portrait mummies showing more relation to Egyptian mummies from earlier dynasties, than they show relation to Greeks and Romans is significant information when it comes to these portraits and how Egyptian they are overall.

This is great!!!!

Is it just me, or is anyone else reminded of the “big eyes” paintings of Margaret Keane?? 😂

Reblogged this on Hillary Peatfield and commented:

Looking into these eyes is traveling through time.

Eerily beautiful.

These portraits are extraordinary.

Cool that most of them (?) are done in wax which makes them look fresh and alive.

I have seen some of these at the University of Michigan Archaeology museum. I have always wished the Portraits could talk to hear their story.

They look like the portraits from Pompeii. Beautiful. Hauntingly familiar.

Looks like a lot interracial relationships during this time in Egypt. I wonder if anyone has done a study on race mixing in Late Antique Egypt.

Not only real but fashionable. Some of the hairdos are spectacular

[…] I am such a nerd, geek, whatever ya choose to call it! I am so fascinated by Egyptian History, archeology is so […]

Once while visiting a museum in Canada, I saw one of these portraits. The woman looked strikingly familiar. Then one of my children stated, “Mommy, that lady looks just like you.”

It was a moment I will never forget.

Art has always been stylized from one generation to the next. Many people of Italian-Greek and Egyptian ancestry have similar feature. As do I and the woman in the portrait who I resemble.

May there memories be eternal! May their souls be blessed!

Almost like they are standing right next to you.

Christina Riggs was nice enough to respond to an email I sent when I was working on a college paper back c. 2001. “First of all” she wrote, “there’s no such thing as ‘just a student’.”

Love her work

Long article, but very interesting. These folks could have been contemporaries of the early church. Their parents could have sat at the feet of Jesus, or followed the apostles…..

[…] Trending story found an hour ago on mikedashhistory.com […]

Amazingly detailed. Some of them look as if they could have been photographs.

Looking at these beautiful portraits is as close as we’ll ever come to truly gazing into the eyes of the past.

Regardless of the ethnicity of the people portrayed here, I find these portraits moving, they were the photographs of the era.

Just looking at these brought me sharply back to a visit to the British Museum when I was young and impressionable and remember now how clearly seeing such portraits on the dead spooked and moved me deeply.

[…] Have you ever wondered what some of those mummified ancient Egyptians looked like in real-life? Mike Dash has a fantastic piece about just that. And it’s filled with really spectacular pictures […]

Such interesting portraits. Could people have had their mortuary portraits painted in life and put away for future use? Or were there a range of stereotypical portraits approximating all the known facial variations? Rather like modern street artists assemble an approximation to live subjects from a standard range of stereotypical features (hence the speed with which they work).

The Amarna Period (18th Dynasty) marked a significant change in Art where the subjects were made to look more human-like vs. the Greek stone sculptures & statues. The Fayum paintings gave life to the individual by adding color and capturing their essence. These portraits were likely done while the person was still alive. This would have been post Hyksos (14th, 15th, 16th Dynasties) with the Shepherd Kings & Greek Hellenists in Egypt… Now we have cameras to take photos. Back in the early 1980’s there were little pamphlets that would circulate the mail encouraging people to go to art school.

Really interesting.

(and now I really must try to sleep)

Number 8 is grumpy!

One of my favorite topics in AH 101 lectures.

The amazingly real likenesses of the Fayum mummy portraits

Very cool article.

This amazing and very interesting!

The same faces continue to manifest down through the centuries.

Haven’t you noticed?

Pingback: ‘Glowing with the flame of eternal life’: A connection across the centuries – Antioch, 1098

Pingback: The Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt | Exploration Vacation

Pingback: Self-Fayum mummy portrait. Encaustic technique – Margaret's blog

Pingback: East Bay Open Studio Weekend One -

Pingback: Mummy Mia: the Fayum Mummy Portraits

Pingback: The Fayum Mummy Portraits - raspoutine.org

Wow thank you so much, I looked everywhere for this website.

It’s dangerous to go alone! Take this.🗡

Pingback: The Fayum Mummy Portraits - domyassignments123

Pingback: The Fayum Mummy Portraits Sample Assignment - Assignment Help Site