A selection of answers to questions posed by readers of AskHistorians. Refreshed most weeks, with the latest postings at the top.

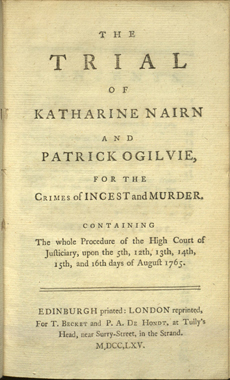

Or go here for more answers from Mike.

Short index to questions (the lower the number, the further down the column the answer will be found)

[52] Who is the performer shown on a leash in this image of the “Congress of Freaks” at the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus?

[51] Henry Ford died of a stroke after seeing footage of Nazi concentration camps. I’ve read that Eisenhower and Nixon alike detested him and other Nazis and sent him the footage before it went public and he watched it alone in his private theatre. Can anyone prove this really happened?

[50] How could Russian coins from 1811 have ended up in Eastern Canada in 1934?

[49] What is the highest rank a commoner could rise to in medieval England?

[48] “In 1927 Chiang Kai-Shek boiled hundreds of Communists alive,” claimed George Orwell. Is this actually true? If not, where could he have heard such a report from?

[47] Did Anne of Cleves really hang the famous Holbein portrait in her castle to troll King Henry?

[46] Did the Empire of Japan seriously try to make conman Ignaz Trebitsch Lincoln the 14th Dalai Lama?

[45] According to Sir James Frazer, in his famous book The Golden Bough, Iron Age kings were regularly sacrificed after completing a fixed term as monarchs, in order to safeguard the fertility of the soil. Was Frazer right about this? What do we know about the kings who were supposedly sacrificed, and the people who killed them?

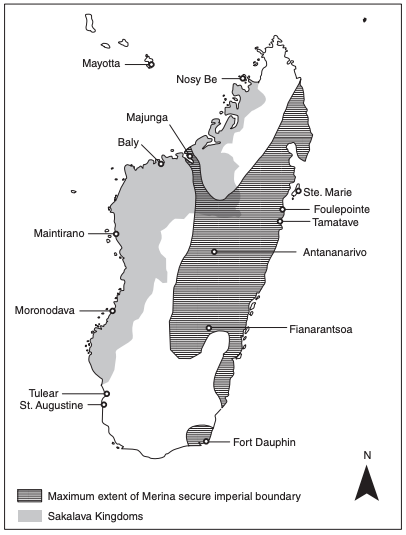

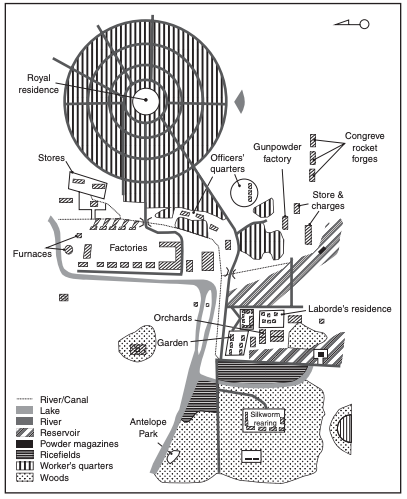

[44] Supposedly Madagascar was pretty close to industrialization prior to European colonialism. Is this true?

[43] Is the story of the Man in the Iron Mask real? If he was, how did he get so well known, even in his contemporary time? And why was his identity concealed?

[42] I live in London in 1670, I have up to date fire insurance and a fire mark for my insurer, a fire has just broken out. How do I tell my insurer I need their fire brigade? What happens if there are multiple fires and all the services are being used?

[41] I’ve seen it claimed, without any sources, that Lord Byron lost his virginity at age nine with his family nurse. What evidence is there that this actually happened and what are the details?

[40] What should we think of the early medieval stories of sky-ships, crewed by sky- sailors, appearing in the air over monasteries and towns?

[39] Does anyone know, for real, which the oldest pub in England actually is?

[38] During the 9th century, a Tang Dynasty author wrote a story about a Black Person (“Negrito”) active during the 8th century in the Tang Dynasty. How many Black People were in Tang China, how did they get there, and what were their lives like?

[37] Were there links between William the Conqueror’s banning of the slave trade in England, and England’s later invasion of Ireland?

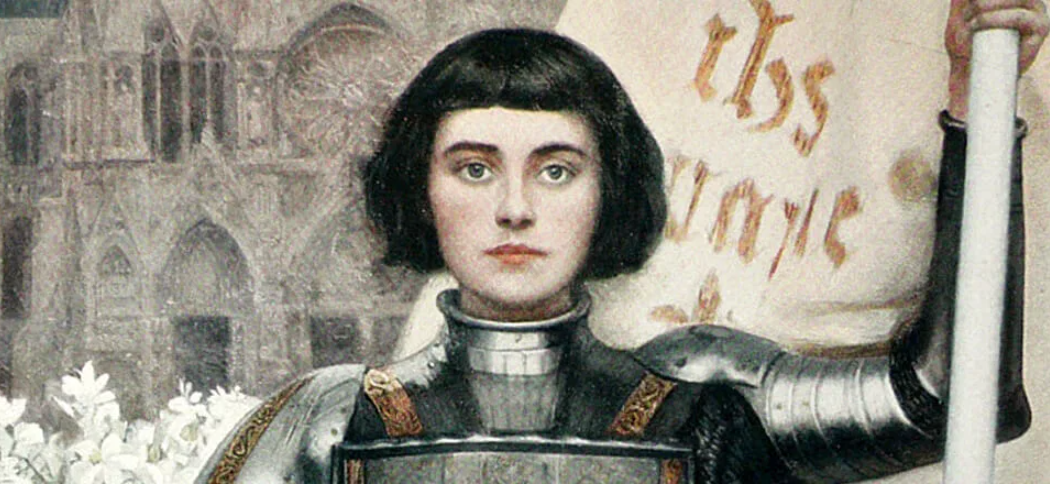

[36] Do we know what Joan of Arc looked like?

[35] Warning: NSFW. Did Wu Zetian really demand that foreign diplomats perform cunnilingus on her in in open court as a show of obedience–or is this a myth?

[34] Why did Fine Gael run a candidate in Inverness, Scotland, in the February 1974 and 1979 UK General elections? They’re an Irish party, so I have no idea why they would run there. It was the same candidate (U. Bell) both times. Any ideas?

[33] Is it true that a portrait of Cleopatra, painted in about 30 BCE by someone who had met her, was unearthed in Italy in 1818? What happened to the image?

[32] Did anyone really say “Her Majesty takes a bath once a month whether she need it or no” about Elizabeth I? Where did this come from? Why is it always referenced in quasi-academic literature without sources?

[31] What do we know about the history of the True Cross after the 1st Century?

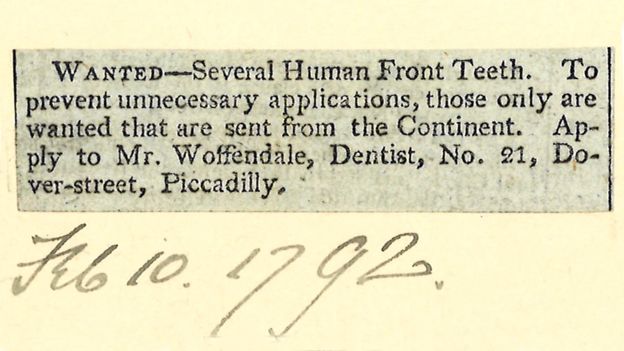

[30] Every once in a while, a website will claim that teeth extracted from dead soldiers at Waterloo supplied dentures across Europe for years. Is this a myth?

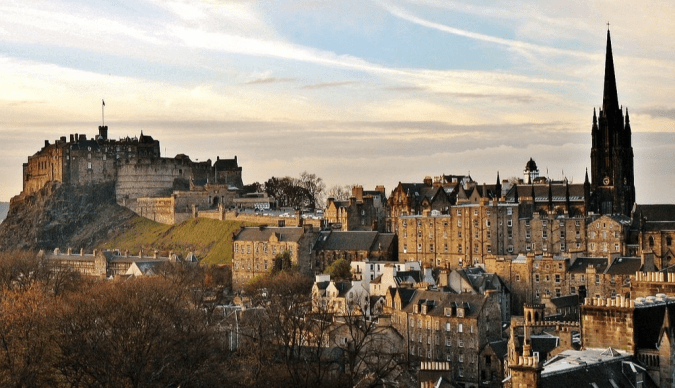

[29] In 1765, a chimney sweep was exiled from Edinburgh for five years for assisting in a public hanging. Why?

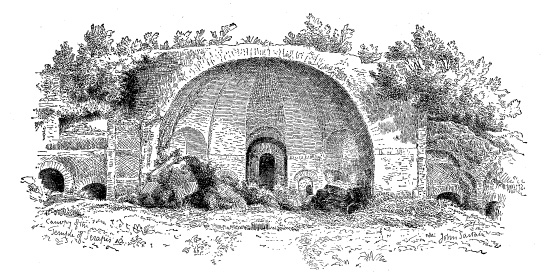

[28] The medieval legend of the Dry Tree.

[27] Did the NYTimes run the headline “The Apostle of Hate is Dead” in response to Malcolm X’s assassination?

[26] There where many types of guilds in the middle ages. Did any of them focus ONLY on illegal activities (smuggler guilds, thieves guild etc) ? Or does this only happen in fantasy novels?

[25] How did the ancient White Horse, a huge hill-figure carved into a chalky down in the south of England in about 1,000 BCE, survive all the political, social and military changes that took place in the area for thousands of years without growing over?

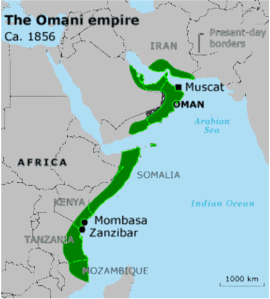

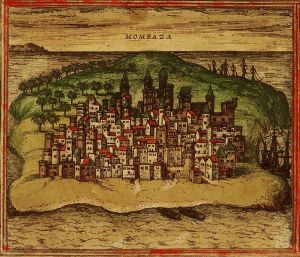

[24] Is it possible that an Islamic city-state, rather like Venice, might have flourished on the desert coast of Somalia in the medieval period, sent envoys all the way to Beijing, and evolved a stable form of republican government that lasted well into the nineteenth century?

[23] How did the general public in England regard Halley’s Comet in 1066? Was universally seen as an ill portent?

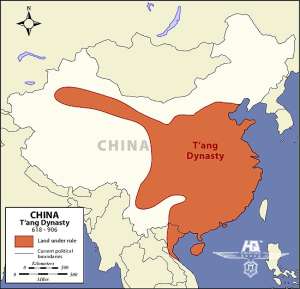

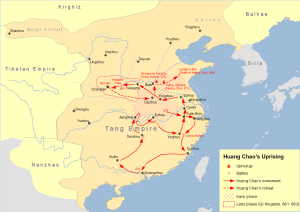

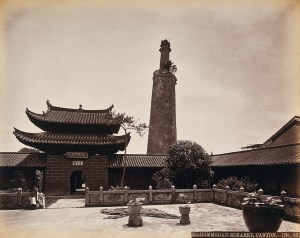

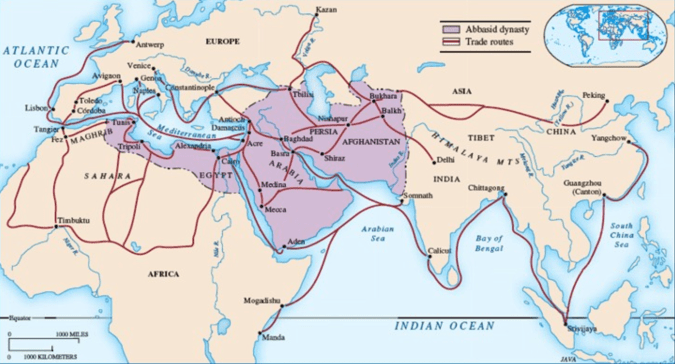

[22] How did the sack of Guangzhou (Canton) in 879, at the end of the Tang dynasty, affect transoceanic trade between the Tang empire and Abbasid caliphate?

[21] I was reading about the history of the stapler and found that the first stapler was made for King Louis XV. “The ornate staples it used were forged from gold, encrusted with precious stones, and bore his Royal Court’s insignia.” Is this true? Does the stapler still exist?

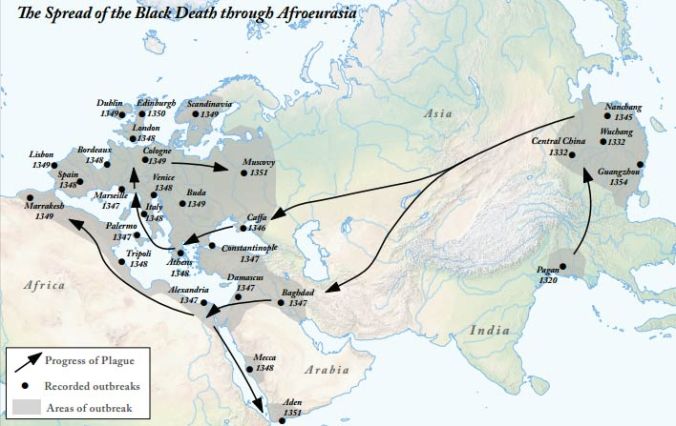

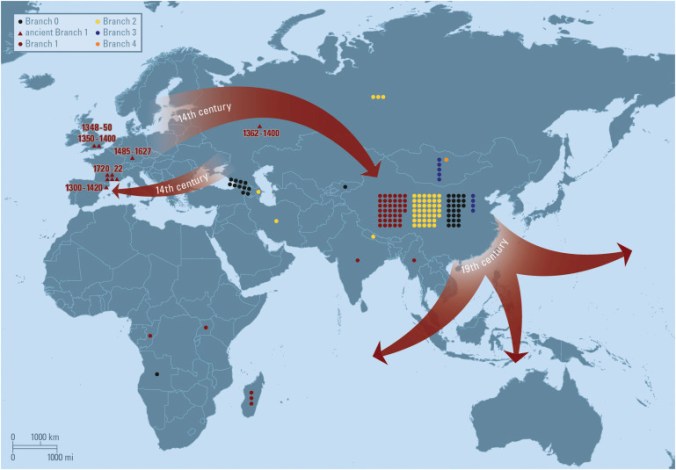

[20] Why can’t I find very much information about the 14th Century Black Death in Asia?

[19] In Les Misérables, Victor Hugo claims that children were kidnapped during the reign of Louis XV, and rumours were whispered of the King’s ‘purple baths’. What is Hugo referring to here, and would the rumours have been common knowledge to a reader at the time?

[18] Do we know of any cases in the Catholic Church when the Advocatus Diaboli (or Devil’s Advocate) successfully argued against someone becoming a saint?

[17] Did Britain fund and direct the 1801 assassination of Tsar Paul?

[16] Did Coca-Cola produce a clear version of Coke for General Zhukov that could be disguised as vodka? If so, for how long was this going on?

[15] Why did Poland have lower rates of Black Death than other European countries during the 1300s?

[14] What is the truth about “getting shanghaied”? Was there such a thing as a bar in 19th-century San Francisco with a chair that dumped drugged people down a trapdoor to kidnap them and force them into the sailing life?

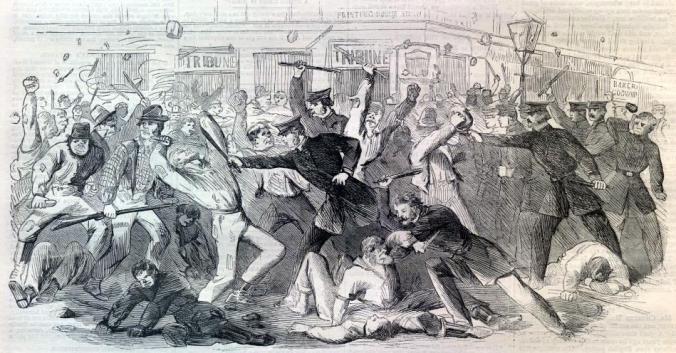

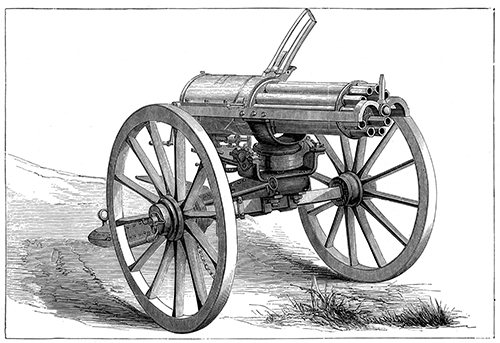

[13] During the New York Draft Riots (1863), supposedly the New York Times defended their office from the mob with 2 Gatling guns. Where did they obtain these guns and ammunition and how did they turn away the mob?

[12] Is it true that Henry VIII feared being attacked so much he had himself bricked into his bedroom every night?

[11] On the giants of Patagonia.

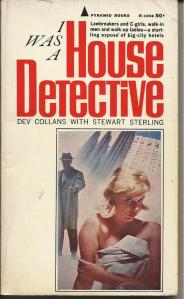

[10] Whatever happened to the hotel detective?

[9] At any point between the end of WWI and the end of WWII was there ever a rise of supernatural beliefs in Japan?

[8] Why did Hatshepsut’s successors attempt to proscribe her memory?

[7] What was the murder rate during the medieval period?

[6] I am a hot-blooded young British woman in the Victorian era, hitting the streets of Manchester for a night out with my fellow ladies and I’ve got a shilling burning a hole in my purse. What kind of vice and wanton pleasures are available to me?

[5] Did British criminals in the 1700s and 1800s really worship a deity called the Tawny Prince? If so, what were the origins of this deity?

[4] How bad would it have smelled in a medieval city?

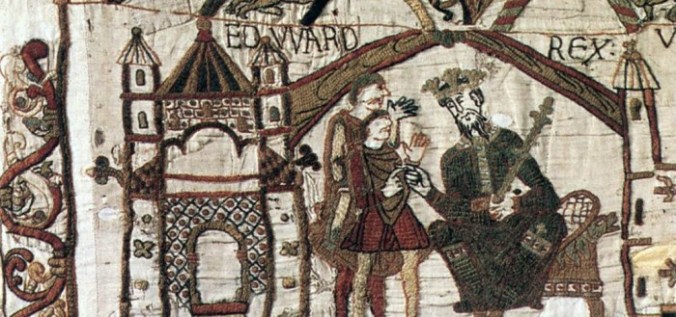

[3] What exactly were the relics on which Harold Godwinson swore his oath to William of Normandy?

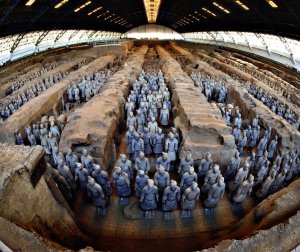

[2] What prompted the first emperor of Qin to have hundreds of scholars buried alive and their works burned?

1] Were the pyramids still kept in repair at the time of Cleopatra?

[52]

Q: Who is the performer shown on a leash in the front centre of this image of the “Congress of Freaks” at the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus?

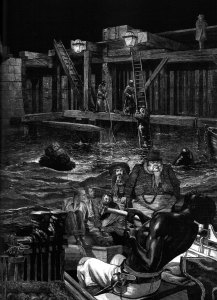

The image you have linked to was taken in 1927 by the New York photographer Edward J. Kelty, and it depicts the acts who appeared in sideshows along the midway of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus that season. Because Clyde Ingalls, the sideshow manager, advertised a list of his performers for this year, which appears in the footnotes of the Barth and Siegel book referenced in the sources below, it’s possible to identify the performer you are interested in as Ho Jo, the Bear Boy. The young man standing over him is a noted Mexican “fat boy” known as Tom Ton. The “leash” you notice is not in fact a restraint – it is actually Tom Ton’s belt, as can be seen by comparing your image with Kelty’s photo of the preceding year’s company.

David Hitchcock, a British academic studying history from below, argues that one purpose of studying history is to “redress that most final, and brutal, of life’s inequalities: whether or not you are forgotten.” I firmly believe this to be true, so let’s see what we can do to rescue the Bear Boy from the abyss of faded memories. We’ll start by looking at what little is known of Ho Jo and his career, and then broaden the enquiry to include Kelty’s role as a circus photographer. Finally – but necessarily, I think – we’ll finish up with a brief look at modern academic takes on the “freak show” as a cultural phenomenon.

Ho Jo’s real name was Jeff Davis. It suggests that he was probably born to a family of formerly enslaved people somewhere in the American South – there is some reason to suspect he may have been a native of South Carolina (see below). While his date of birth and place of origin are not known, and I’ve searched unsuccessfully for a death certificate that might reveal them, the first notices of his showman’s career begin to appear in 1920. This makes it most likely that he was born sometime shortly after 1900.

Davis appears to have experienced a form of dwarfism, though it’s not possible to offer a proper diagnosis on the basis of a couple of photographs. He was Black, and wore a furred body suit as part of his act and to compliment his “bear boy” persona. The Tampa Tribune of 29 January 1928, which gives the only account of Ho Jo’s actual performances that I’ve been able to trace, says that he was billed as “The Bear Boy from Haiti” (a fairly typical piece of carnival exoticism, but also one that – given the US occupation of Haiti from 1915 – purportedly explained his presence in the US) and “the only four-footed human being on earth”. His act was to shin up trees and poles, “using all fours just like the real article.”

Within his own world, Ho Jo kept some pretty elite company. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus was the largest, best-funded and most prestigious of all the travelling shows in the US at this point, with a staff somewhere north of 300 people and its own 60-car railway train, almost a mile long – so perhaps it’s no surprise that Kelty’s 1927 photo also depicts a number of the best-known “freak show” performers of the 1920s, some of them still recognisable today. They include Olga the Bearded Lady (top row, far left), two giants – Jim Tarver (top row, third left) and Jack Earle (top row, second from the right) – Major Mite, billed as the smallest man in the world (top row, just to the right of centre), and Eko and Iko, the two albino Black men with dreads, wearing sashes, on the right hand side of the front row, who were usually billed as “Ambassadors from Mars”. Possibly the most recognisable figure in the image for many people today is Minnie Woolsey, who was billed as Koo-Koo the Bird Girl (top row, wearing a plumed cap and glasses and standing next to Major Mite), though she certainly wasn’t considered an especially major draw at the time this picture was taken. Her modern fame rests on her memorable appearance in the cult 1932 horror movie Freaks, by Dracula director Tod Browning, in which she is seen dancing on the table in the wedding reception sequence.

Despite his membership of the “Congress of Freaks”, Ho Jo, like Koo-Koo, never ascended to top billing in the circus sideshow world. He was at best a second rank performer, and he only seems to have appeared as part of the Ringling Congress in 1926 and 1927; he did not even spend the whole of the 1927 season with the show, also appearing at the “Dreamland Circus Sideshow and Chinatown” at Coney Island in May of that same year.

Davis died in Columbus, Ohio, in the spring of 1931. It’s unclear from the brief death notice that appeared in Billboard – the trade magazine nowadays noted for covering the music industry, but then the main communications medium for show people – what he was doing in Columbus. Possibly he lived there, but it seems more probable, given the date (too early for circus season in Ohio) and the need to earn a living, that he was appearing at a local dime museum, a building converted to display “living wonders” including “freaks” and speciality acts such as sword swallowers and fire eaters. A handful of exhibitions of this sort were permanent attractions, but most toured from city to city like the circus, stopping in one place for a few weeks or a month before moving on. Ho Jo had toured in the south with the Cash Miller museum in the winter of 1929-30, exhibiting in Atlanta late in November and moving on to Chattanooga three weeks later in the company of Hamda Bey, billed as a “Hindu fakir”, whose act likely involved sword swallowing and perhaps a bed of nails; Mme. Ensly, “the homeliest woman in the world”; Twisto, an “india rubber man” – meaning contortionist; Edna-George, a claimed hermaphrodite; and “the Original Sailor Joe”, a heavily tattooed man. Probably he was with a similar show in ’31 when he fell ill and was taken to the University Hospital in Columbus. He died there on 28 March of tubercular peritonitis – TB that has spread from the lungs to infect the abdominal cavity. He was probably aged about 30 or 35 at the time of his death, and must have been ill for some time.

What, though, of Davis’s life? Performers in the “freak shows” of this period fell into one of three broad categories, each of which offered a different level of status within the community. At the summit of this hierarchy were the “born freaks”, people who were different from those around them from birth. The most remarkable members of this category – people such as Frank Lentini, the man with three legs – secured top billing and were the best paid; some, as we shall see, were capable of “carrying” an entire show of otherwise indifferent performers. Ho Jo fell into this category, as did bearded women, Koo-Koo the Bird Girl (who had Virchow Seckel dwarfism), fat men and women (irrespective of the causes of their obesity), and some “hermaphrodites”. Next came the “made freaks”, who had turned themselves into sideshow attractions. This category included tattooed people and also various performers whose act rested on some form of fakery or “gaff”. Perhaps the most remarkable example I’m aware of was Mortado, the Living Fountain, a German man who had had holes bored through his hands and feet. According to Daniel Mannix, he kept these wounds open by driving wooden plugs into them in between performances; on stage, metal pipes linked to the water supply would be run into them and turned on to produce the “living fountain” effect. The final category of “freak show” performers, and the least prestigious because they were most easily replaced, were novelty acts such as fire-eaters and strong men. Inside the side show tent, all performers would be introduced to crowds by “talkers”, who spun exotic and utterly fictitious stories to explain how they had been discovered and came to be onstage. Jeff Davis’s billing as a native of Haiti is an example of this. Mortado’s wounds were explained with a story that he had survived crucifixion in some African or Latin American jungle by members of an indigenous tribe. Similarly, the “Original Sailor Joe” who exhibited with Ho Jo would not simply have displayed his body art – he would have been talked up with some story explaining how he came to be so extensively tattooed – probably one involving shipwreck and “savages”.

The scant material that survives for Ho Jo’s life allows us to slot him into the sideshow hierarchy, and so understand a little about his likely standing in the show community, but, other than that, it tells us only a little about him. The chances are that he had little formal schooling. Depending on his home circumstances, he may possibly have decided on a career in showbusiness for himself, but it is perhaps most likely that he was “scouted” by someone with associations with the circus world who saw his potential, as were Eko and Iko were (see below). In the latter case it’s fairly possible that he spent time in a state asylum or institution of some sort as a result of his disability, which means he need not necessarily have started work in his teens. The Billboardevidence shows us that he must, nonetheless, have been in show business no later than 1918 or 1919, and he seems to have maintained a long business relationship with Jay Warner of the Diamond Amusement Co., who operated out of premises in the small town of Union, South Carolina, from at least 1916 before eventually shifting the base of his operations to Bay St Louis, Missouri, and getting into the manufacture of Ferris wheels and merry-go-rounds. In those days, Warner ran a 10-in-1 show (the circus equivalent of a dime museum, being ten assorted acts in a single tent, accessible on payment of a single entrance fee). By 1921, Ho Jo was being billed as “half-man, half-monkey”; five years later, he was with the Ringling-Barnum operation – billed as “the Greatest Show on Earth”, and by far the largest and most prestigious travelling circus in the world at that time. To work as part of its “Congress of Freaks” and on the main drag in Coney Island when that resort was still close to its peak, Ho Jo must have offered more than just a little person for crowds to gawp at. His act must have been worth watching, too.

If not quite at the top of his profession, Ho Jo was clearly in demand during his career – over the course of the 1920s, Billboard featured at least half a dozen want ads placed by showmen explicitly seeking his services and urging him to contact them to take up bookings. On the other hand, he seems to have been quite alone at the time of his death, and out of contact with whatever family he may have had. The death notice that appeared in Billboard – placed there by a local correspondent named Mark Verdon (about whom I have been able to discover nothing other than his then address and an association of some sort with Hilderband’s United Shows, a West Coast circus, which does suggest he was a fellow showman) says that “the address of any surviving relative was not known”. Verdon appealed for “acquaintances of ‘Ho Jo’” to send contributions towards the cost of his interment to an undertaker in the city. A total of $75 was needed by 6 April to allow a decent burial to go ahead; Billboard only published the appeal in an issue dated 11 April which actually appeared four days earlier – and hence cannot have reached readers before the 6th. It seems most likely that Davis was interred in a pauper’s grave.

The photographer who immortalised Ho Jo as a member of the “Congress of Freaks” thus occupies an important place in his history. Edward J. Kelty was a one-time newspaper reporter from San Francisco who relocated to New York after serving as a Navy cook during the First World War and opened a photographic studio in midtown Manhattan. For roughly eight months of the year, Kelty’s stock-in trade was photographing weddings, banquets and conventions in the city. For the remaining four, when the summer shows were touring, he travelled up and down the east coast, taking photographs of most of the major names of the period, including the Sells- Floto, Hagenbeck-Wallace and Cole Brothers circuses as well as Ringling Bros.

Kelty invested time and trouble in his travels because of the business opportunities. His main work as a group photographer meant that he was one of the very few people operating at this time to own the large-format cameras needed to take “banquet shots”. One of these, weighing about 25lbs (11kg), produced 11×14 inch images (28x36cm) that were several times the size of the standard exposures of the time, and it was this camera that Kelty used for his annual photos of the “Congress of Freaks”.

He followed highly-structured workdays, erecting his camera at dawn and getting to work straight after breakfast, starting with the general staff and turning to the performers last of all to allow time for them to don costumes and make-up. By noon he would have exposed about 30 photographs, taking three or four alternate shots of each large group. Afternoons were spent processing exposures, after which he would solicit orders and make the necessary prints that same evening, so that his customers received their orders before the circus moved on to its next pitch in some other town.

Kelty was not an employee of the circuses he photographed. Instead, he sought their permission to be on the lot, and help in corralling numerous performers into the same place at the same time for his images. In return, he made copies of the results available for publicity purposes. He also made part of his living by selling prints to the people captured in his pictures, paying a half-share of these proceeds to the circus. On his return to New York, he produced and marketed catalogues of his images, and sold prints to circus fans as well.

We know only a little more of Kelty than we do of Jeff Davis, but it seems he must have had an affinity for the people whom he photographed in order to capture them so well. Barth calls him the “Cecil B. DeMille of still photography”. He declined with the fortunes of the circus, too. The travelling show gave way to movies as the central form of entertainment popular with most Americans, and the Great Depression had a devastating effect – fewer potential customers could afford the prices. As a result, the ranks of the largest “railway shows” fell from 13 in 1929 to just three by 1933. Smaller shows were impacted in at least equal proportion, sometimes closing down overnight and leaving both performers and their animals stranded without pay in some small town. Sells-Floto, one of the largest and most successful of circuses in the 1920s, was folded into the Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey operation in 1929, eventually becoming just a brand name for its logistics operation.

“At some point between 1938 and the early 1940s,” Barth notes, “Kelty was forced to sell a significant number of his negatives to Knickerbocker Photos, a company that distributed photographic images to magazines, periodicals, and textbook publishers.” He subsequently moved to Chicago, where he worked as a vendor at Wrigley Field. According to a story told to Barth by several different collectors of his photographs, he sometimes met Chicago bar bills by handing over some of his remaining negatives. He died in 1967.

Throughout this short essay, I’ve placed the term “freaks” and the phrase “freak show” in inverted commas, in recognition of the fact that it is a negative term, and that employment of “freaks” by sideshows and dime museums is nowadays only a little less controversial than the use of animals by circuses. Interest in these entertainments, once ghettoised to a relatively small group comprising former performers, carneys, and enthusiasts, has increased somewhat with the growth of the field of disability studies, but there is nonetheless absolutely no consensus in the historiography as to how best to view either the shows, or the people who performed in them.

One school, which features the likes of Daniel Mannix – an Admiral’s son turned carney turned pulp writer – makes the case that “freaks” were generally better off as members of travelling shows than they would have been in any other likely circumstances. There is some justification in such claims; the vast majority of “freaks” came from relatively or absolutely impoverished backgrounds, and those born during the heyday of the carnivals, between about 1860 and 1930, lived at a time when there were very few social safety nets in place for anyone considered badly disabled or unable to work. Absent a family willing and able to take care of them, many such individuals wound up in local or state institutions for the disabled, where the conditions and food were awful and their treatment often grim. Generally barely educated, and in many cases mentally disabled, they were often unable to speak out on their own behalf, and might easily suffer from neglect, not to mention sexual or physical abuse. For Mannix, the contrast between such fates and life with the carnival was a stark one. In the shows, “freaks” not only lived among others like them; they could potentially earn a decent living and had status that was often actually relative to the extent of their disabilities. As Mannix notes,

Such expert showmen as Charles S. Stratton (“General Tom Thumb”)… travelled extensively and acquired a comfortable fortune, as did Chang and Eng, the original Siamese twins, Percilla and Emmett (the monkey-girl and alligator-skinned man) and Al Tomaini (a giant) and his wife Jeanie (a half woman), who ran their own side show and retired to Florida on the proceeds… It would seem to me that all these freaks were happier and more useful than they would have been locked up in institutions.

He then continues:

During the three years I worked as a sword-swallower and fire eater in a carnival sideshow, I lived and performed with freaks. A good freak would top every outfit on the Midway, even the nude posing girls, and it’s mighty hard to beat sex as an attraction…

I once worked with a freak who was billed as the “Pig-Faced Boy”. He was one of the best natured persons I’ve ever known. A hunchbacked dwarf, the boy’s face came almost to a point, and vaguely suggested an animal’s snout. His parents stubbornly refused to acknowledge the boy’s deformity and kept insisting that he’d grow out of it.

To Pig-Face, the carnival seemed like paradise. For the first time in his life, his strangeness had become an asset. He knew that the success of the 10-in-1 (carny term for the sideshow) depended largely on him, and he felt a glow of self-respect. He was surrounded by people who admired and even envied him. He told us with amused pride that some ordinary dwarfs with another carny were trying to imitate his appearance by using greasepaint and New Skin. “They still look like ordinary people,” he told me proudly. “Not me – I really look like a pig!”

The contrary position points out that experiences of this sort were not the norm, and that only performers of unusual intelligence and considerable self-confidence could hope to experience really good conditions and build appreciable wealth. Other “freaks”, perhaps most obviously the so-called “pinheads”, whose microcephaly severely impacted their mental capacities, were largely at the mercy of the people who ran the sideshows; some of them were treated well, others more poorly, but it’s hard to resist the conclusion that these performers were often regarded more as possessions than family members (being sometimes literally bought and sold), and experienced conditions that were not all that far removed from slavery.As Robert Bogdan points out in his academic study of “freak shows”, the motives and private characters of the men who ran the travelling shows might vary, but they were apparently never entirely honest nor straightforward; the very nature of their job militated against that. Clyde Ingalls, the sideshow manager for whom Ho Jo worked at the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus in the 1920s, had a reputation for treating most of the people who worked for him quite well – but he also authorised his ticket-sellers to systematically short-change the “rubes” who were his paying customers, and demanded a share of the proceeds of this grift. Bogdan similarly points to the “revolt of the freaks”, which supposedly took place in 1903 when a group of performers from Barnum & Bailey’s “Prodigy Department” wrote a letter to the New York World, lodging a

respectful though emphatic protest against the action of some person in placing in our hall a sign bearing the, to us, objectionable, word “Freaks,” and committing another person to call aloud, “this way to the Freaks.”

This turned out to be a product of the circus’s PR department, deliberately initiated and orchestrated for the purposes of generating publicity.

The new research done by Beth Macy – author of the biography of George and Willie Muse, the albino brothers exhibited as Eko and Iko, the Ambassadors from Mars, who must have known Jeff Davis – uncovers the same sorts of ambiguities. In one sense, the brothers endured a truly horrific personal history. They were born into considerable poverty; their family were sharecroppers in Truevine, Virginia, where the boys went to work in the tobacco fields from the age of six. There they were tracked down by a circus scout, who noticed their potential as freaks, lured them with an offer of sweets, and then kidnapped them and took them off to perform (unpaid) in the sideshow – from which they were discouraged from leaving by being told that their parents were dead. It was not until nearly 30 years later that their mother, Harriett Muse, discovered that her sons were still alive, and visited the circus to confront the sideshow proprietor and recover her sons.

The complications of the Muse brothers’ story do not end there, as Macy is honest enough to admit. They returned home, only for their father, Cabell – a gambler and local bully – to start charging locals cash to see them. After his death they returned to the circus – paid this time, though they were repeatedly fleeced by the people for whom they worked; there, they might earn a living for themselves, but, as Sukhdev Sandhu puts it, “they could be everything but themselves. They were everywhere but home.” And though Willie Muse lived to be 108, and was noted for his optimistic outlook and even temperament, he always did have a bad word to say for the man who had abducted him – repeatedly terming him a “c%cksucker”.

The only sensible conclusion seems to be that we need to take the stories of these performers case by case. For every Charles Stratton – white, highly intelligent, an active partner in his own exhibition – there were likely many Muse brothers. We do not know enough about the life or the times of Jeff Davis to know for certain which category he fitted into. His background, and his disability, certainly had the potential to place him the same category as the Ambassadors from Mars. Ho Jo’s lonely death, his lack of family, and a likely pauper’s burial, suggest the same. On the other hand, the highly fragmentary evidence of Billboardrather paints him as a showman of some repute, and an active member of a travelling fraternity who possessed the regard of the people with whom he worked.

Whatever the truth, we at least know a little more about him now – as a performer, but also as a human being who does not deserve to be forgotten. I hope that it’s been interesting to read a little bit about his life and times.

Primary sources

Billboard, 10 January 1920, 14 May 1921, 3 June 1922, 2 February 1924; 10 April 1926; 23 April 1927; 14 May 1927; 6 August 1927; 28 January 1928; 24 March 1928; 16 June 1928; 11 August 1928; 3 November 1928; 23 November 1929; 14 December 1929; 11 January 1930; 18 January 1930; 11 April 1931 p.70 [death]; 5 February 1949

Clarion Democrat, 15 Sep 1927

Miles City Star, 23 July 1938

Tampa Tribune, 29 January 1928 [details of performance]

Secondary sources

Miles Barth, Alan Siegel and Edward Hoagland, Step Right This Way: the Photographs of Edward J. Kelty(2002); Robert Bogdan, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (1988); Michael Chambers, Staging Stigma: A Critical Examination of the Freak Show (2008); Daniel P. Mannix, Freaks: We Who Are Not As Others (1976); Sukhdev Sandhu, “Truevine by Beth Macy review – a remarkable story of freakshow racism”, Guardian, 17 March 2017; John Jacob Woolf, “Fabricating Freakery: the Display of Exceptional Bodies in 19th Century London”, Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis, 2016

[51]

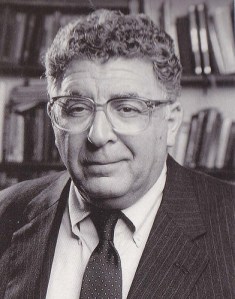

Henry Ford with a Ford

Q: Henry Ford died of a stroke after seeing footage of Nazi concentration camps. I’ve read that Eisenhower and Nixon alike detested him and other Nazis and sent him the footage before it went public and he watched it alone in his private theatre. Can anyone prove this really happened?

A:The story sounds far too neat to be true, and the dates do not remotely fit – but the claim that Henry Ford died as a direct result of his first exposure to the realities of a Nazi rule that he had once expressed real admiration for is at least a contemporary one, and it comes from a supposed eyewitness.

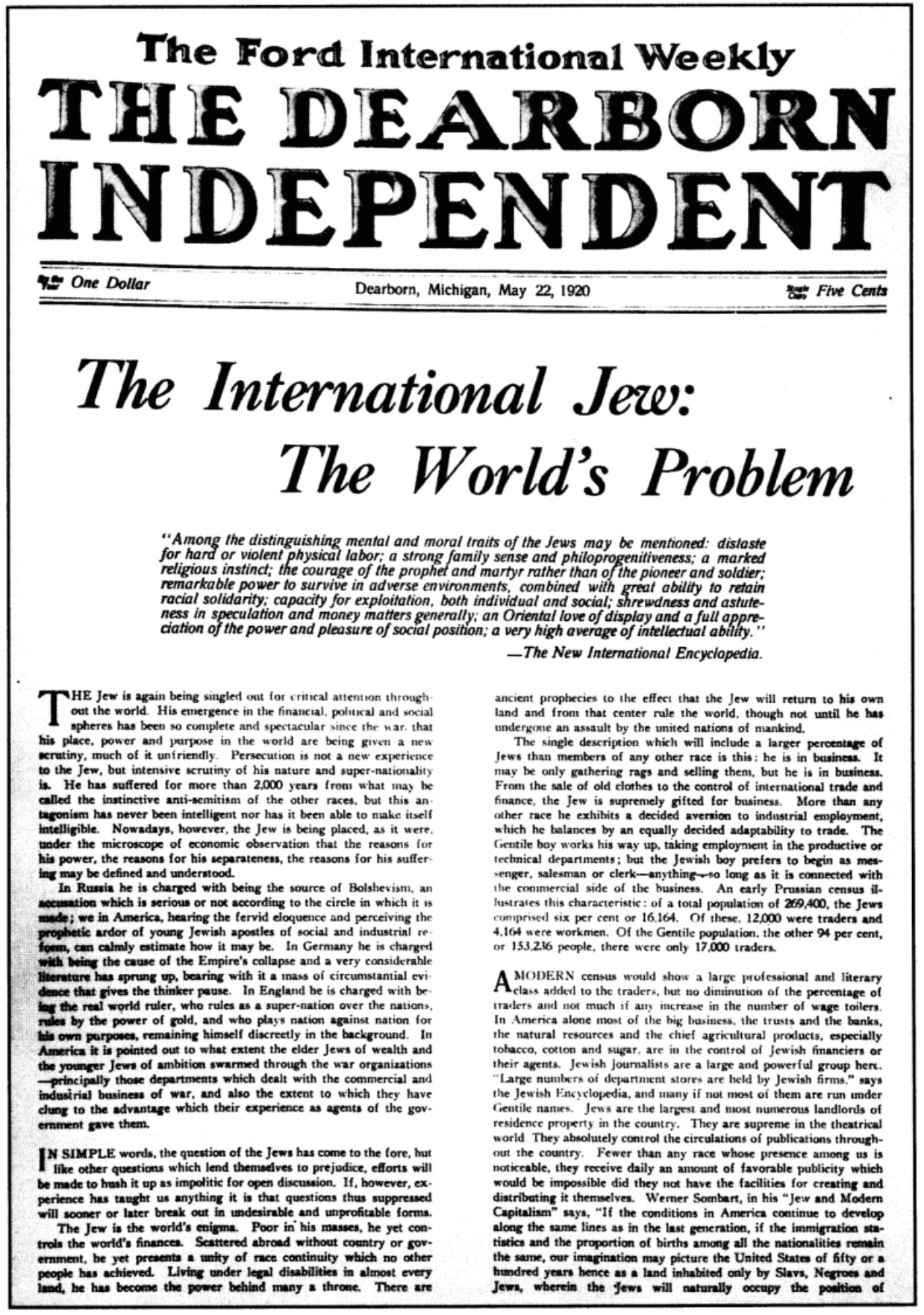

We should probably begin by recalling that, while Henry Ford is best-remembered by the general public for the central part he played in devising the assembly-line production system, and hence in creating a mass market for cars during the first half of the 20th century, historians have also long been interested in both his battles against unions and his intense antisemitism. Ford used some of the millions he made from industry to bankroll publication and distribution of tens of thousands of copies of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a Tsarist-era fraud designed to provide proof that a Jewish conspiracy secretly ruled the world. He also purchased his hometown newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, turning it into a mouthpiece for his views, and the Independent subsequently published a 91-part series of antisemitic essays, ghosted for Ford, which he later turned into a four-volume book titled The International Jew. Ford distributed the book via Ford dealerships, circulating about half a million copies in total.

This activity, coupled with Ford’s celebrity and the respect in which he was held for his success in business, played a significant part in legitimising antisemitism in the US between the wars. It did not go un-noticed by the Nazis, either. A correspondent from the New York Times who interviewed Hitler late in 1931 reported that he had a large portrait of Ford hanging over his desk, and historian Hasia Diner has noted that “Hitler could look at Ford as somebody who was – let’s call him an age-mate… [He] was very much inspired by Ford’s writing.” The Nazis awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle in 1938 (he was the only American to receive this honour), and in 1945, while awaiting trial at Nuremberg, Robert Ley – the Nazi bureaucrat in charge of the Labour Front organisation, who was heavily implicated in the use of slave labour in German factories – wrote to Ford, making much of their shared antisemitism and requesting a job. During the 1930s, the Ford Motor Co. became a haven for Nazi sympathisers, and Jonathan Logsdon has also pointed out that, even before the Nazis came to power, Ford was already notorious for his ruthless and anti-union business practices:

Ford’s chief investigator, Harry Bennett… emerged as a major influence on company policy. Bennett created a Gestapo-like agency of thugs and spies to crack down on potential threats to Ford, such as union men. “To those who have never lived under a dictatorship,” reflected one employee, “it is difficult to convey the sense of fear which is part of the Ford system.”

Ford, in short, was at the very least a strident antisemite and poster-boy for views the Nazis would agree with who had also earned the bitter enmity of organised labour, especially in the manufacturing heartland around Detroit. And all this helps to illuminate the background to the story you have heard.

The actual source for the story of Ford’s fatal encounter with filmed evidence for Nazi atrocities is Josephine Gomon (1892-1975), a feminist and social activist who was a prominent figure in Detroit politics from the 1920s into the 1970s. Gomon, who was active in pushing for access to birth control, for civil rights and civil liberties, was politically liberal and had few views in common with Ford. However, she did know him well. During the Depression years of the 1930s, while working as executive secretary for Frank Murphy, then the mayor of Detroit, she was sent to negotiate a loan from the Ford Motor Co. to tide the city’s overstretched finances over a financial crisis. Ford was sufficiently impressed by Gomon’s negotiating skills (an obit notes that she “convinced him that he’d hate the idea of New York bankers having a stake in Detroit more than he disliked Murphy”) that he hired her during the war to take a role recruiting women to work in a Ford-controlled aircraft factory. She was patriotic enough to agree, but “added the ingredient of equal treatment for them, while campaigning for better conditions for all workers” and also became firm friends with Walter Reuther, the radical and highly effective leader of the United Auto Workers union. All this made Gomon extremely unsympathetic to Ford’s politics, and to a large extent to Ford the man.

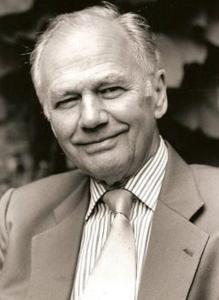

Josephine Goman, Detroit activist and Ford’s head of women personnel at the Willow Run plant, is the source of the story investigated here

In the 1970s, in semi-retirement, Gomon composed two manuscripts which she seems to have intended for publication. One focused on Frank Murphy, the other on Henry Ford. Although they never were published, both scripts still exist among the Gomon papers in the special collections of the University of Michigan Library, and the story of Ford’s viewing of documentary footage of the Nazi concentration camps comes from drafts of the latter work, which had the working title “The Poor Mr Ford”. A brief excerpt from this reminiscence, probably written down almost 30 years after the fact, accompanied by a longer precis of the relevant passage, can be found in Max Wallace’s critical history of Ford and Charles Lindbergh’s roles as Nazi sympathisers and cheerleaders, The American Axis [pp.358-9]. Wallace was the first historian to quote directly from Gomon’s MS (Carol Gelderman had referenced it in a footnote two decades earlier), and I would guess that it is ultimately via Wallace that you have encountered the story:

Each person has their own unique reaction to the stories coming out of Germany immediately after the war ended, but none perhaps as ironic – some would say fitting – as Henry Ford’s. In the spring of 1946, the American government released a public information film called “Death Stations” documenting the liberation of Nazi concentration camps by US troops a year earlier. In May, Henry Ford and a number of his colleagues attended a private showing of the film at the auditorium of the Ford Rouge River plant, a few days before the documentary was to be released to the general public. Most of the assembled Ford executives sat rapt as the first gruesome images of the Majdanek concentration camp flickered on the screen. They reeled in horror at the graphic footage, which included stark images of a crematorium, Gestapo torture chambers, and a warehouse filled with victims’ belongings. When the lights went on an hour later, the company executives rose, shaken, only to find Henry Ford slumped over in his seat, barely conscious. Sitting there witnessing the full scale of Nazi atrocities for the first time, the old man had suffered a massive stroke, from which he would never fully recover. The story sounds apocryphal, and it is never mentioned in any company history or Ford biography, but the account comes from a credible eyewitness source. It is described in the unpublished memoirs of one of the Ford Motor Company’s highest ranking executives – Josephine Gomon, director of female personnel at the Willow Run bomber plant – who was present at the screening. Ford’s lesson, she wrote, seemed appropriate:

“The man who had pumped millions of dollars of anti-Semitic propaganda into Europe during the twenties saw the ravages of a plague he had helped to spread. The virus had come full circle.”

So that’s the story. But, as I noted above, Gomon did not write it down at the time, and at the very least had some personal and political motives for suggesting that Ford had suffered such a collapse in such circumstances. Whether or not she misremembered, elided, or simply invented her story, it does not match up our understanding of how knowledge of the Holocaust reached the United States, nor with the known facts of Ford’s final decline and death.

To deal with knowledge of the Holocaust first: “Death Stations”, as several sources refer to it – though probably the US Army propaganda short Death Mills is meant – does exist, and it was first released in the spring of 1946; one focus was indeed on the Majdanek extermination camp, at Lublin in Poland, and the film did contain sequences showing the crematorium and investigators casting a warehouse piled high with victims’ belongings. However, this was far from the first evidence most Americans had seen of the death camps. Baron points out that “the widespread dissemination of footage and photographs of the liberation of the concentration camps in newspapers, newsreels and magazines” began as early as 1944. A Universal newsreel, “Nazi Murder Mills” was widely shown in US cinemas in May 1945, the narrator noting that “for the first time, Americans can believe what they thought was impossible propaganda. Here is documentary evidence of sheer mass murder – murder that will blacken the name of Germany for the rest of recorded history.”

As a result, Baron notes, “revelations about the carnage in Europe… seeped into the consciousness of most Americans,” and the impacts are clearly visible in public opinion polls conducted in 1945, in which 84% of respondents said they were convinced that “Germans have killed many people in concentration camps or let them starve to death.” Even though the Holocaust was certainly not central to the way in which Americans thought about and remembered the Second World War during the 1940s, and even if Ford was among the minority who did not see this evidence when it was first published, or he chose to ignore it, it seems unlikely that he could have been so entirely ignorant of the Holocaust as late as 1946 as Gomon’s account implies.

(It’s worth noting in passing here that neither Eisenhower nor Nixon figure at all in any of the accounts of Ford’s final illness or death that I have gone over, and Nixon was in 1945-46 a relatively junior officer in the US Navy, working on aviation contracts in Baltimore, and then only just beginning his own political career. However, Eisenhower absolutely did play a central role in arranging for filmed evidence from concentration camps to be widely disseminated – as Shandler puts it, he was “at the forefront of establishing the act of witnessing the conditions of recently liberated camps as a morally transformative experience.” This may be one reason why his name has become attached to the version of the story that you’ve heard.)

The first of the nearly two-year-long series of antisemitic editorials published by Ford in the hometown newspaper that he owned

The question of whether Ford ever reassessed his antisemitism, and the extent to which he can in any sense be considered to have been a Nazi sympathiser, is a fairly complex topic to engage with. His views were, I think, deep-grained, but antisemitism was only one of a very large number of prejudices that he held, if by far the most damaging among them. David L. Lewis of the University of Michigan has noted that Ford “championed birds, peace, Prohibition… waterpower, village industries, old-fashioned dancing, reincarnation, exercise, carrots, wheat, soybeans, plastics, hard work, and hiring of the handicapped,” but “attacked Jews, jazz, historians, ‘parasitic’ stockholders, alcohol, rich foods, meat, overeating… lipstick, rolled stockings, horses, cows, pigs, and chickens” as well as unions). His antisemitism was also something difficult to deal with within triumphalist tone of much of the biographical material written about him and his industrial success. Generally speaking, Ford biographers have tended to underplay the issue, while specialists in Jewish history and antisemitism have tended to focus on the 1920s and Ford’s publications in the Dearborn Independent, and not on his perspectives on the Nazi state of the 1930s or during World War II.

Further complexity is added by the fact that Ford was a businessman, and was undoubtedly aware that his views were not shared by large numbers among his customer base – indeed, some of his customers boycotted Ford products because of the Independent‘s series. In addition, and while there’s little doubt that the articles reflected Ford’s positions, it’s actually too simple to say that he “wrote” them himself – he was too busy for that, and authorship of the series has usually been ascribed to his influential personal secretary, Ernest Liebold – another antisemite, but one who, I think it’s probably safe to say, held his position at least in part because his views on Jewish people coincided with Ford’s.

Anyway, what can be said about Ford’s evolving views on antisemitism and Nazism amounts to this: Ford publicly repudiated antisemitism in the 1920s. He temporarily halted publication of the Dearborn Independent articles as early as 1922, and formally apologised for the series as early as 1927. After 1927, he does not seem to have made further antisemitic comments in public forums. But this doesn’t mean that he had changed his mind – his apology actually emerged as part of a negotiated settlement for a libel case brought against Ford by Aaron Sapiro, a Jewish lawyer he had accused in the Independent of exploiting farmers’ cooperatives. As such, it cannot be assumed to be sincere.

Similarly, and for potentially the same reasons, Ford seems to have taken some care not to publicly identify with or praise the Nazis even before they came to power, much less caused the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939. He was approached as early as 1923 to provide funding for Hitler, and met with a Nazi emissary named Kurt Ludecke, who was sent from Germany while Hitler was imprisoned after the Beer Hall Putsch. Carol Gelderman recounts that Ludecke made what he hoped would be a well-received pitch to Ford. He

told Ford that Hitler’s ultimate rise to power was inevitable. As soon as he had power, he would inaugurate a social program for which the Dearborn Independent‘s articles provided much suggestive material. All that was needed to get an immediate application within Germany of the views that Ford and Hitler held in common was money. “The Nazis were the only important active group in the world with a positive program by establishing a new non-Judaized order,” he continued, but they were helpless without money. Ludecke sensed Ford’s unresponsiveness. “If I had been trying to sell Mr Ford a wooden nutmeg, he couldn’t have shown less interest in the proposition. With the consummate Yankee skill, he lifted the discussion back to the idealistic plane to avoid the financial question “.

No payments were forthcoming. Ford’s same tendency to put his and his company’s needs and profit ahead of Germany’s later caused him to refuse another approach, this time to produce Volkswagen’s for Hitler in Germany, and, when he accepted the Grand Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, he stated that he saw it as a gift from the German people and did not accept it because of any sympathy with Nazism. Ford did, however, agree to build a company-owned assembly plant in Berlin where trucks and V8 engines were assembled. Four or five other factories followed. Gelderman suggests that this move, too, should be seen as part of a business strategy and not an active Ford investment in Nazism or the Nazi programme:

By this time, American executives hardly knew what was going on because of Nazi interference. By 1940 the plant was turning put turbines without [Ford’s] knowledge. In Cologne a heavy infantry vehicle was being produced without Dearborn’s consent. By spring of 1941, Hitler occupied the continent from Russia to the Pyrenees. All Ford facilities on the continent, except the Danish plant, served Hitler. After Pearl Harbor, all these Ford plants became enemy property.

Ford openly criticised Hitler’s renunciation of the free market, but his views on Nazi antisemitism are harder to gauge. In the late 1930s he did take some public steps to underscore his supposed renunciation of antisemitism. He ordered that 12% of Ford advertising funds be channelled to Jewish newspapers, and attended a number of testimonial dinners for prominent Jewish figures, and urged that America should welcome Jewish refugees from Nazi persecution. In 1937, he issued a statement to the Detroit Jewish Chronicle “disavowing any connection whatsoever with the publication in Germany of the book known as The International Jew.” On the other hand, says Gelderman, “he did little to stop the proliferation of The International Jew within or without Germany” and “apparently made no connection between [the suppression of the free-market] and the suppression of the Jews that his own antisemitism had done so much to foster.”

Finally, in this regard, Ford was – so far as I can tell with only a little time to devote to the research – silent on antisemitism, the Holocaust and Nazism after 1939, though more can probably be said on this matter. During the war, he strongly backed the American war effort. The Willow Run factory, where Gomon worked, employed 60,000 workers to build B-24s, aircraft and tank engines, trucks, jeeps and other hardware. By 1945-46, when it’s reasonable to suppose that Ford must have become aware of the Holocaust, his physical and mental state was almost certainly too compromised for him to have commented meaningfully on the issue, even if he had been minded to.

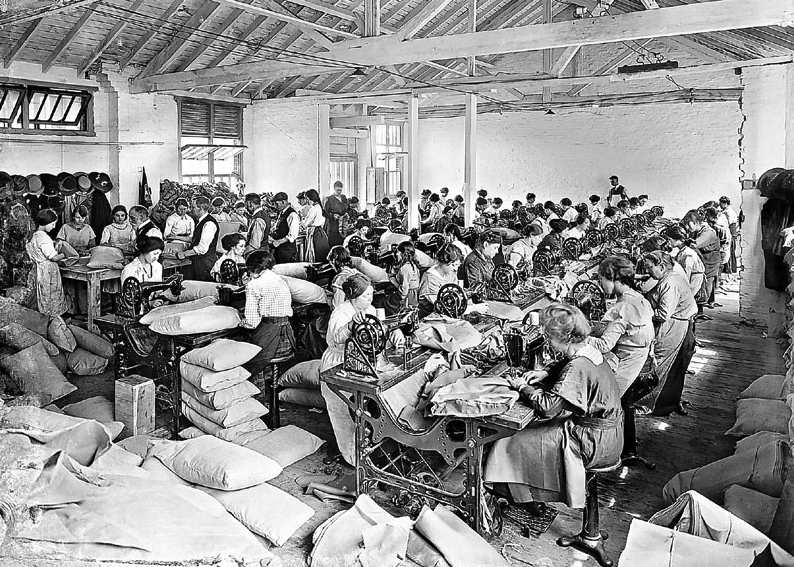

The vast Ford production facility at Willow Run, MI, where Josephine Gorman headed up female personnel during World War II

Next, we need to consider what is known of the circumstances of Ford’s decline and death. He suffered not one, but several, strokes – the first in 1938. His recovery from this event was rapid and, apparently, complete, but he experienced a second in 1941 that was far more debilitating – physically, Ford seemed largely undiminished well into his eighties, but from 1942-3 he does seem to have suffered from mental effects associated with the experience of strokes, and biographers note that from that time he was intermittently irritable, suspicious, disordered and confused. Neither of these two incidents was publicised, however, and Ford’s third stroke – by far the most serious in the sequence – was also hushed up. This final cerebrovascular event occurred early in 1945, and it took place at Richmond Hill, an estate Ford owned in Ways Station, south-east Georgia, which is about 870 miles south-east of the Ford plant where, in the story you have heard, Ford experienced his stroke. When Ford was well enough, he returned north to Fair Lane, his home in Dearborn, Michigan, but – the narrator of the PBS documentary of Ford’s life observes – thereafter he “remain[ed] mentally and physically languid, often failing to recognize old friends and associates, and [was] carefully kept out of the public eye.”

In short, then, the stroke that felled Ford, and probably contributed to his eventual death on 8 April 1947, occurred more than a year before the release of the documentary Death Mills/“Death Stations” which is supposed to have occasioned it. We know of no fourth stroke, and – while the secrecy that surrounded Ford’s first three near-brushes with death suggests that it is far from impossible that he did have another after his return to Michigan, that it is possible this coincided with a showing of Death Mills to Ford Company employees, and that Josephine Gomon could have witnessed this – the consensus among historians and Ford biographers is that it was the Richmond Hill event that impacted him most. We can even go further than that, since Carol Gelderman, a Ford biographer, noted [endnote to pp.374-75 of her book] that she had

asked Henry Ford II whether his grandfather had a stroke at this time. He did not know, but authorized Stanley Nelson, executive director of Henry Ford Hospital, “to release to [the author] any information in the records of the hospital about any stroke or strokes that my grandfather may have had in 1945 or in any other year.” (Letter of January 30, 1979.) According to these records, Ford had no stroke in 1945.

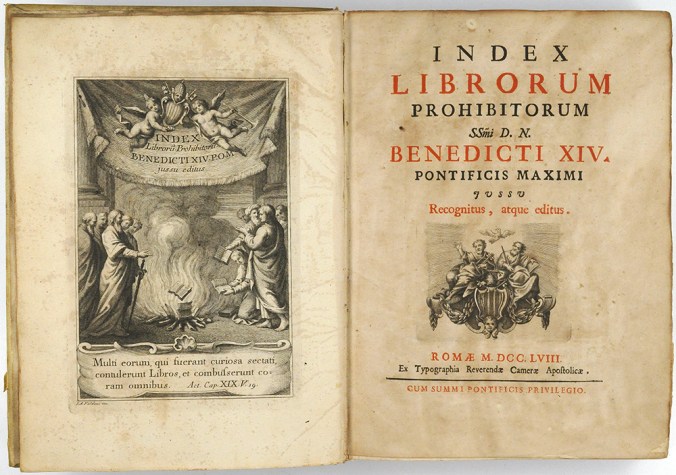

Still from Billy Wilder’s Death Mills (1946), showing personal possessions taken from victims of the Majdanek extermination camp. This was the film that Ford was supposedly watching when he suffered his fatal stroke

To sum up: even if Ford did suffer a collapse of some sort during a viewing of Death Mills, what Gomon witnessed was apparently not a stroke, much less a fatal seizure of any sort. It is difficult to be certain how shocked he would have been by the evidence that the film contained, or even that he had not previously seen film or still images from the concentration camps, plenty of which were in widespread circulation more than year earlier. And there was a further one-year gap between the rough date Gomon that says she watched Death Mills with Ford in the spring of 1946 and Ford’s eventual death, from a cerebral haemorrhage, in April 1947 – so it seems completely impossible to link any viewing of that film by Ford (for which Gomon in any case remains our solitary source) directly to his death. That death – pretty clearly – can be attributed to a combination of old age (Ford died aged 83) and his significant and debilitating long-term health problems, without any need to appeal to the shock effect of a belated recognition of the consequences of his long-term association with Nazism. If Ford did watch the film, moreover, he certainly did not do so alone, and there’s no evidence that he was sent a copy of the footage by either Eisenhower or Nixon.

With all this said, I do think it is broadly feasible that might be at least a grain of truth in Goman’s account. Gelderman notes that “there is no reason to doubt Mrs Gomon’s veracity; the author checked her trustworthiness with an impeccable sources.” So perhaps Ford didattend a screening of the film, and perhaps he was affected by the viewing sufficiently for that to be obvious to Gomon. I think it is highly unlikely, given that we do know of Ford’s three other events, that a really serious incident would have gone unnoticed and unrecorded by the people around him, or by Ford biographers, however. It seems to me more likely that three separate events – Ford’s 1945 stroke, a 1946 viewing of Death Mills attended by Gomon and other Ford executives, and Ford’s eventual death in 1947 – got telescoped in Gomon’s 1970s memoir, and then further compressed in the version of the story that you heard, becoming connected as one contiguous (and morally satisfying) series of events. But the details in the account you’ve heard are a pretty poor match for the history, I’m afraid.

Sources

PBS interview (2012) with Hasia Diner, Professor of American Jewish History & author of The Jew in the United States, 1654-2000 (2004); “Henry Ford and Anti-Semitism: A Complex Story“, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation; “Ford dies in lamplit bedroom, cut off by floods,” Washington Star, 8 April 1947; “Josephine Gomon, libertarian, dies in Detroit,” Daytona Beach Morning Journal, 15 November 1975; Robert Aitken and Marilyn Aitken, “Pride and prejudice: the dark side of Henry Ford,” Security 32 (2005); Neil Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews: the Mass Production of Hate (New York, 2002); Lawrence Baron, “The first wave of American ‘Holocaust’ films, 1945-1949,’ American Historical Review 2010; Carol Gelderman, Henry Ford: the Wayward Capitalist (New York, 1981); Jeffrey Herf, Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (Cambridge, 1984); David Lanier Lewis The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company(Detroit: 1976); Stefan Link, “Rethinking the Ford-Nazi connection,” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 49 (2011); Jonathan R. Logsdon, “Power, ignorance and anti-semitism: Henry Ford and his war on Jews,” Hanover Historical Review 1999; Jeffrey Shandler, While America Watches: Televising the Holocaust (New York, 1999); Daniel Schulman, “America’s most dangerous anti-Jewish propagandist,” The Atlantic, 7 November 2023; Max Wallace, The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich(New York, 2003); Barbie Zelizer, Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory Through the Camera’s Eye (Chicago, 1998)

[50]

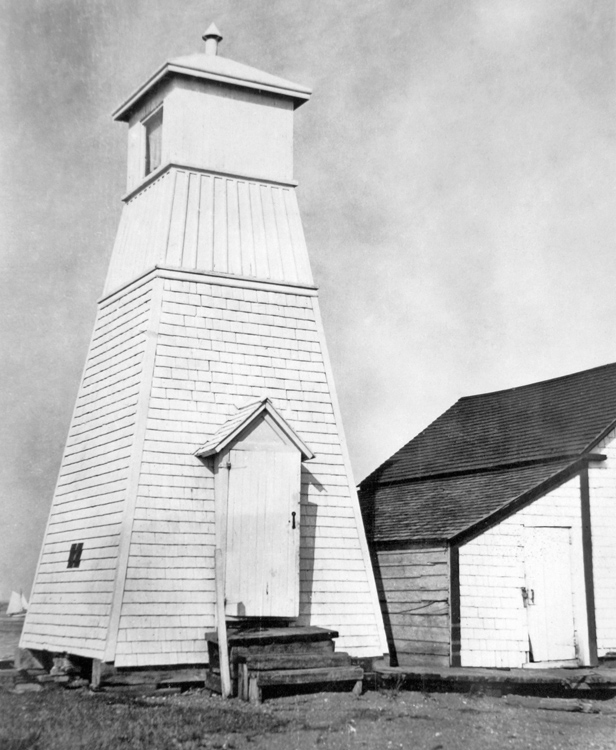

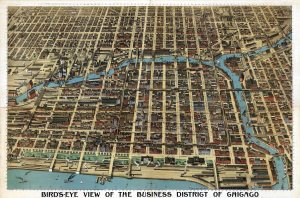

The beach at Carron Point, New Brunswick

Q: How could Russian coins from 1811 have ended up in Eastern Canada in 1934?

I came across a curious article from 1934 saying that a treasure was found in buried on or near a beach around a lighthouse near Bathurst on the Northern New Brunswick coast in Eastern Canada. It was a kettle full of mysterious coins. The lighthouse keeper who found it hoped it was a pirate treasure, but it turned out to be 111 two kopek coins from the Russian Empire. As far as the article mentions they were all from 1811. This, apparently was worse than worthless at the time, except for the value of the copper.

I don’t know much more than that, and there doesn’t appear to be any follow up. Entirely hypothetically speaking though, how might that pot of copper have ended up there? Who could have brought such a thing over? How would a Russian even have managed to end up in Bathurst, New Brunswick, Canada on or around 1811?

A: Coins are durable objects, and, as a result, they have cropped up in some pretty surprising places over the years. Favourite oddities include Roman currency found in Iceland and – a particular surprise, this one – a coin dating to the reign of the Emperor Hadrian that was excavated from under several feet of soil about a hundred miles up the river Congo in central Africa in about 1890. There is also an ongoing investigation into the mystery of how a small group of coins minted in the coastal African state of Kilwa (in modern Tanzania) in about 1200 found their way to the Wessel Islands, 5,000 miles to the east, off the north coast of Australia, where they were uncovered during the Second World War.

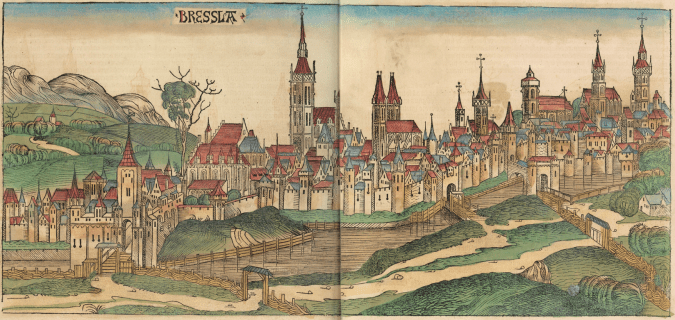

Coins minted in the Sultanate of Kilwa in about 1300, and found in the Wessel Islands, Arnhem Land in 1944.

There is a tendency, when dealing with stories of this sort, for the imagination to conjure up a one-step, and generally romantic, solution to such mysteries – coming up with adventurous scenarios that might have taken a Roman legionary of the second century way south of the Sahara, or envisioning a Kilwan trading ship disabled by the monsoon winds and drifting thousands of miles off course to strand her crew amidst the unintelligibly alien culture of the indigenous Yolngu peoples of Australia. The reality, insofar as we can work it out, tends to be both more complex and also a lot more prosaic. The Congo coin had a high silver content, enough to make it a valuable item of exchange hundreds of years after it was struck in Rome and the empire that had made it had declined and fallen. Rather than being dropped by a solitary, way-out-of-place Roman soldier, it’s far more likely that it made its way south via a lengthy series of transactions. Possibly these started on the north shores of the Mediterranean, but continued in the Roman provinces of North Africa, from where the coin eventually made its way into the hands of desert nomads – who crossed the Sahara and then traded it to someone in the Sahel, from whence it eventually continued its journey south. Or, perhaps more likely, the coin stayed in the Mediterranean for centuries, eventually to find its way on board a Portuguese ship headed for the Kingdom of Kongo sometime after contact was established between the two states in the 1480s. Either way, it’s probable that no one person took the coin from its point of origin to its point of discovery, and the same most likely applies to the Wessel Islands coins too – which were found mixed with Dutch currency dating to the 17th century, and so, we can deduce, probably didn’t actually come direct from the Swahili Coast in the 13th century.

A Russian 2-kopek coin minted in 1812, during the reign of Alexander I

Without having seen the article you read (which I’d love to have a reference to…), it’s hard to know what to make of the find that you are interested in, but a few thoughts do occur. First, the coins were found inside a kettle. That strongly suggests they were not trade objects but rather a hoard, deliberately buried by someone who wanted them to stay together in one place, and hoped to come back eventually to recover them. The fact that the coins were all minted around the same date points in the same direction. But the value of the coins was very low, even in 1811, and Alexander I kopeks were minted from soft copper. That meant they contained no precious metals that would have made them intrinsically valuable to anyone outside Russia in the early 19th century, whether as trade objects or as a source of useful materials in areas where there are no naturally occurring lodes of workable metal (I commented in an earlier response on the ways in which iron carried across the Pacific on disabled Japanese merchant ships may have eventually found its way into use by indigenous communities in the Pacific north-west). So, actually, it’s unlikely the coins you are interested in made their way to eastern Canada via the sort of lengthy series of unremarkable financial transactions I was describing above – any such trades would have tended to break up the collection of currency found in the hoard, and the out-of-place discoveries I have mentioned involved single coins, or at most a small handful of them, not more than a hundred apparently struck in the same time or place. But this realisation, by itself, doesn’t take us a whole lot closer a solution to your mystery.

I can make a couple of observations that might move us a bit further forward, nonetheless. Firstly, as is well known, Russians certainly were present in what’s now Canada in about the period we are interested in – Alaska was an imperial colony until its purchase by the US in 1867. That fact, however, is almost certainly less significant than it might at first appear – New Brunswick is an entire continent, and some 3,000 miles, away from any Russian settlement of the period, and getting from one side of the Americas to the other as early as the first decades of the 19th century would have been an incredibly difficult, lengthy and arduous affair, one that would have almost certainly required careful planning and involved a distinct objective. It’s very difficult to imagine what the latter might have been, nor why anyone would think it a good idea to take a big bag of kopeks with them on what would have been an unimaginably arduous trek. Overall, I think it extraordinarily unlikely that any individual or group of Russians would have made their way from Alaska to the Canadian Maritimes overland in the first half of the 19th century.

More probably, the coins arrived in Canada from the opposite direction – coming from the east. The existence of a hoard of identical coins suggests to me that they were once the property of a single person who placed some value on them and had some potential future use for them, which in turn suggests the person who buried the hoard was probably a Russian. By far the most obvious reason for such outsiders to come to New Brunswick in the 19th century would have been involvement in the fisheries there. Ships and merchants from what is now New Brunswick were heavily involved in the highly lucrative cod industry, for instance (there was also a prominent local logging industry which might also have proved attractive to immigrants). We do know that at least one Russian reached the eastern Canadian coast as a result of his involvement in the fishing trade – William Hyman, who was born into a Russian Jewish community in Lódz, in what is now Poland, in 1807, fetched up in Gaspé, Quebec, in about 1843, and built up a successful stake in the dried cod business there. By the time of his death in 1882, Hyman was one of the most successful businessmen in town, accounting for about 10% of the port’s exports, and he was able to bequeath to his heirs

a dock, storehouses and a warehouse at Gaspé, a hotel and several properties and mortgages in the Forillon peninsula region, and six fishing establishments… He had also accumulated many securities in banks at Quebec City and Montreal, and owned a Montreal residence where he had spent the winters since 1874.

Of course, a man like Hyman would have been far too wealthy, and no doubt far too integrated into Canadian society, to have wanted to bury a hoard of old low-value imperial coins on a remote beach. But his very existence does at least establish that some Russians did make their way to there Maritimes in the relevant period. How plausible, then, is it to suggest that the coins you are interested in were once the property of some Russian fisherman? I have had a look for evidence of Russian fleets taking part in the great cod trade, and not turned up anything to suggest that this happened – sailing from the eastern Baltic, through the North Sea and then all the way to the Grand Banks would have been a costly and challenging voyage that would have taken a lot longer than the journey from a western European port like Bristol, and it would most likely have been easier for any Russians in the market for Canadian cod to have bought lightly salted and dried end product on the open market in Europe than to have fished for them themselves in the distant North Atlantic. Moreover, while the religiously observant Russians did eat large quantities of fish (Sarhrage & Lundbeck point out that the proscriptions of the Orthodox church prohibit the consumption of meat on 132 days of the year), these were plentifully available from nearer waters – the main sources were the Caspian, the White Sea, and from European freshwaters. In addition, the main Russian fish import in the 19th century was not cod, but the very differently-flavoured, and much more popular, salted herring, which made up almost 80% of imports when reliable figures become available from the start of the 20th century. Those fish, moreover, were sourced from Hanseatic ports in the Baltic, and in general local conditions would mitigate against any attempt to build a commercially-viable long-distance fishing trade based out of Russian Baltic ports – Tallin, for example, is typically iced-up for anything up to 175 days each year.

Now, none of this absolutely rules out individual Russian sailors working their way west and taking part in the Canadian fisheries as part of the crew of a foreign ship, and it’s certainly possible that this did occur from time to time. But why would such a man want to burden himself with a large quantity of low-value coins that would have been useless in Canada as items of exchange? A 2-kopek coin of the period you’re interested in weighed 13g, or about half an ounce – a hoard of more than a hundred of the things would have weighed in at about 1.4 kilos, or more than 3lbs, which seems an awful lot to carry on board ship and then take off that ship in Canada for no readily apparent reason. Finally, if – as their burial and their placement together in a kettle certainly suggests – the Bathurst find was a hoard, why would any visiting sailor planning eventually to return to the only country where those kopeks could actually be spent choose to abandon them at the spot where they were found?

Carron Point lighthouse in 1933

There are a couple of interesting points to make in this respect. First, the lighthouse at Bathurst is located at Carron Point. This is a promontory at the mouth of Bathurst harbour, but (thanks to the large size of the harbour) it is located almost two miles outside the town. That’s a long way for a sailor in port to lug a heavy sack of coins – why make that journey? Second, while it’s not clear from your post whether or not the spot was chosen because of the proximity of the lighthouse, it makes a certain amount of sense to assume it was – you note the coins were found pretty close by, and, potentially, the location of the lighthouse itself would have provided a straightforward means of relocating an otherwise hard-to-find burial spot. If that’s the case, then we also know something about the date of the deposit, since the first lighthouse on the site was not constructed until 1871.

All of these clues suggest to me another possible origin for the coins. William Hyman had left Russia to escape the limited opportunities and often active persecution endured by Jewish people in the empire, and the first significant wave of Russian emigration to Canada actually roughly coincided with the construction of the Bathurst lighthouse, beginning from the 1870s; today more than 620,000 Canadians (including a few thousand in New Brunswick) have Russian heritage. While the first significant group of emigrants were actually around 7,000 ethnically German anabaptists who settled in Manitoba, from the 1880s much larger numbers of Jewish refugees fled the pogroms that fairly regularly occurred during this period. Most of these people settled in eastern urban areas such as Toronto and Montreal. Might a poor emigrant, whose wealth largely comprised low-value coins that they’d planned to convert into the local currency, but never had the opportunity to, have been the source of the find?

Well, it’s possible, and I’d say actually that it’s fairly plausible that at least one Russian family from this diaspora might have made its way to a relatively flourishing port like Bathurst in this period (even today, it’s still the fourth largest town in New Brunswick – in the 19th century it would have been more prominent than that). But once again I’d have to say that the specific nature of the find makes the idea unlikely – it’s almost vanishingly improbable that a single Russian family’s source of wealth would comprise 3lbs of coins of identical date, rather than a far less heterogenous collection of higher-value currency. I’d say that the coins in the hoard that turned up in Bathurst must have remained together for a reason.

And this is where both my imagination and my research skills begin to fail me, I’m afraid. The homogeneity of the find seems to suggest someone with a direct connection to a Russian mint, or a Russian bank, but the gap between the date these coins were struck and the earliest plausible date for their deposit at Carron Point remains a real puzzle – there’s no obvious reason why such a large number of low-value coins would have stayed together for so long. Perhaps the hoard was itself the product of a find of some sort, of a bag of coins that had never been opened since it was minted, and was found at the back of a dusty shelf, or locked up in a cupboard somewhere? Might it have reached Canada as part of some commercial transaction carried out some time in the 19th century?

But then again, why bury such a low-value collection of coins in the first place? Why would anyone make the journey all the way to Carron Point to leave them? I’d guess the coins were more likely taken to the beach by boat than lugged up to the lighthouse from Bathurst on foot, but, beyond that, I’m stumped for a specific motive. The hoard might even have been placed there as a joke, or “uncovered” as part of a publicity-seeking hoax, to see what wonderment it might generate. I don’t know the exact date of your newspaper clip, but there were a couple of major finds of hoards in 1934 that might have provided inspiration for such an exploit, such as the discovery in August of that year of gold coins worth more than $11,000 buried in a cellar in Baltimore.

Well: if the last of these possibilities is correct, then we can say one thing: the depositor would probably have been gratified by your curiosity, and my willingness to spend a couple of pretty interesting, if ultimately unsuccessful, hours attempting to investigate on your behalf.

Sources

The Canadian Encyclopedia

Dictionary of Canadian Biography

John Murray Gibson, Northern Mosaic: the Making of a Northern Nation (1939)

Dietrich Sahrhage & Johannes Lundbeck, A History of Fishing (1992)

[49]

The cathedral at Canterbury

Q: What is the highest rank a commoner could rise to in medieval England?

A: Archbishop of Canterbury.

The church was long noted as the means by which those from less than exalted backgrounds could best make both a good living, and, potentially, their mark, both theologically and politically. A high proportion of successful prelates were the younger sons of prominent families – men who were unlikely to inherit significant amounts of land. Careers in the church offered such men livelihoods, and family connections the leverage to achieve higher office within the ecclesiastical community. These sorts of career decisions also applied to family members who faced more significant barriers to advancement than mere order of birth; thus at least two of the Canterbury archbishops of the medieval period – Ralph Nevill and John Stafford – were the illegitimate sons of noted families.

A second, and much smaller, group of eminent clerics made their way up the ecclesiastical ladder from lower positions than that as a result of talent or patronage. Cathedral cities and monasteries typically provided opportunities for schooling for children from much more modest social backgrounds, and there was always demand from the royal government for educated men who could read and write. While those able to take advantage of such openings were rarely if ever from the very bottom rungs of society, sons of artisans and merchants could and did get themselves “talent-spotted” by superiors who valued their scholastic or administrative skills.

Very occasionally, a child from such a background might make it all the way. The best-known example from the medieval period was that of Thomas Becket, whose disagreements with Henry II, and eventual death within the precincts of Canterbury cathedral at the hands of a group of the king’s knights, made him perhaps of the most famous of all English archbishops; he was the son of a successful London merchant. And Edmund of Abingdon, who became archbishop a few decades after Becket, was probably the son of a wool merchant.

Edmund’s career offers a good example of the means of ascent that could be employed by men from more humble backgrounds in this period. His family background was sufficiently affluent to allow him to attend the University of Paris, after which he moved to the university at Oxford and became well known as an expert on Aristotle and a teacher of grammar. All university teachers this period were also ordained priests, and further alternating periods spent as a scholar at Paris and Oxford were interrupted by time spent in possession of various church benefices and preaching the crusade. Eventually one of Edmund’s old university pupils, Walter de Gray, became Archbishop of York, and was able to use his influence to advance the career of his old master. Edmund ultimately became compromise candidate for the archiepiscopal throne at Canterbury in 1233.

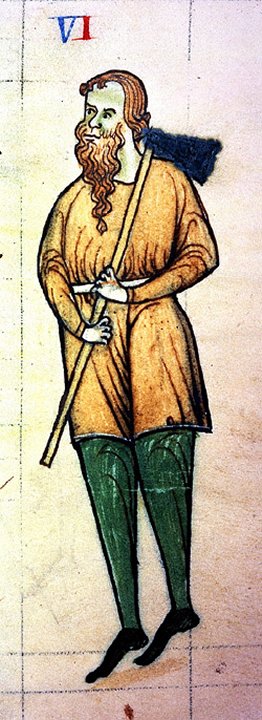

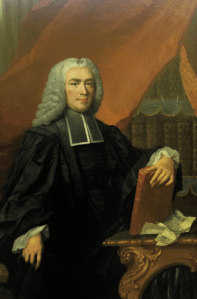

Walter Reynolds – from small-town bakery to Archbishop of Canterbury

Such a career was rare, but certainly far from unknown in the medieval period. While we often have only the barest details about the parentage and early careers of many eminent churchmen (and are not completely sure, for example, that Edmund’s father really was a minor merchant), the archbishop who rose from the must humble background of all in the medieval period was almost certainly Walter Reynolds, who held the see at Canterbury from 1314-27. He is generally accepted to have been the son of a baker in Windsor, Berkshire, which meant that he began his church career in a town with very strong links to the English monarchy. This seems to have been critical; Walter became a clerk in the court of Edward I and there he met the king’s son, the future Edward II. He quickly became a close friend of both the future monarch (who in 1309 described him as one who, “active in our service from our earliest youth, has came to enjoy our confidence ahead of others”) and of Edward’s lover, Piers Gaveston. As a result, he moved to take an administrative position as keeper of the young prince’s wardrobe.

Reynolds’s successful career, then, was entirely the result of royal favour and patronage. He was provided with the livings of a series of parishes (which he probably rarely if ever visited), which provided him with a good income, and in 1308 became Bishop of Winchester. He was named Chancellor of England in 1310, and Archbishop of Canterbury in 1314. He was sufficiently politically astute to switch sides with remarkable adroitness after Edward was overthrown by his wife and her lover, Sir Roger Mortimer, in 1327, preaching the text ‘Vox populi vox Dei’ (in which he justified the revolution and seems to have approved renunciation of homage to Edward II) only one day after the deposition of his old friend and patron.

Reynolds has an equivocal reputation. For Robert of Reading, he was

a man decidedly unclerkly, and so ill-educated that he was entirely unable to set out the form of his own name … Having ceremoniously received the insignia of an archbishop, he used them as an ox does its horns, in robbing churches and oppressing the religious, indulging in immoderate filthiness of lust.

Edward II – still the only English monarch to be the subject of his own “anal rape narrative”

For John of Trockelowe, on the other hand, the archbishop was a far more benign influence, the “man by whom those tribulations [of the church in England in this period] could best be assuaged.” Modern historians have viewed him increasingly favourably. In the overall judgement of his biographer, J. Robert Wright,