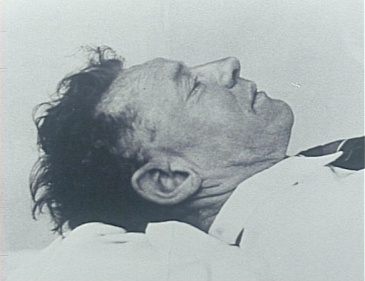

Mortuary photo of the unknown man found dead on Somerton Beach, south of Adelaide, Australia, in December 1948. Sixty-three years later, the man’s identity remains a mystery, and it’s still not clear how – or even if – he was murdered.

Most murders aren’t that difficult to solve. The husband did it. The wife did it. The boyfriend did it, or the ex-boyfriend did. The crimes fit a pattern, the motives are generally clear.

Most murders aren’t that difficult to solve. The husband did it. The wife did it. The boyfriend did it, or the ex-boyfriend did. The crimes fit a pattern, the motives are generally clear.

Of course, there are always a handful of cases that don’t fit the template, where the killer is a stranger or the reason for the killing is bizarre. It’s fair to say, however, that nowadays the authorities usually have something to go on. Thanks in part to advances such as DNA technology, the police are seldom baffled anymore.

They certainly were baffled, though, in Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, in December 1948. And the only thing that seems to have changed since then is that a story that began simply—with the discovery of a body on the beach on the first day of that southern summer—has become ever more mysterious. In fact, this case (which remains, theoretically at least, an active investigation) is so opaque that we still do not know the victim’s identity, have no real idea what killed him, and cannot even be certain whether his death was murder or suicide.

What we can say is that the clues in the Somerton Beach mystery (or the enigma of the “Unknown Man,” as it is known Down Under) add up to one of the world’s most perplexing cold cases. It may be the most mysterious of them all.

Let’s start by sketching out the little that is known for certain. At 7 o’clock on the warm evening of Tuesday, November 30, 1948, jeweler John Bain Lyons and his wife went for a stroll on Somerton Beach, a seaside resort a few miles south of Adelaide. As they walked toward Glenelg, they noticed a smartly dressed man lying on the sand, his head propped against a sea wall. He was lolling about 20 yards from them, legs outstretched, feet crossed. As the couple watched, the man extended his right arm upward, then let it fall back to the ground. Lyons thought he might be making a drunken attempt to smoke a cigarette.

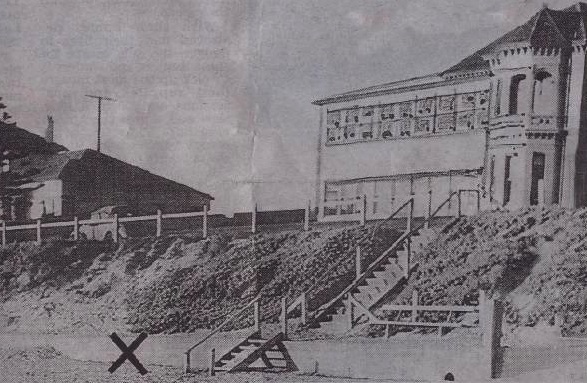

“X” marks the spot – Somerton Beach, showing the place where the mystery man’s body was discovered on 1 December 1948.

Half an hour later, another couple noticed the same man lying in the same position. Looking on him from above, the woman could see that he was immaculately dressed in a suit, with smart new shoes polished to a mirror shine—odd clothing for the beach. He was motionless, his left arm splayed out on the sand. The couple decided that he was simply asleep, his face surrounded by mosquitoes. “He must be dead to the world not to notice them,” the boyfriend joked.

It was not until next morning that it became obvious that the man was not so much dead to the world as actually dead. John Lyons returned from a morning swim to find some people clustered at the seawall where he had seen his “drunk” the previous evening. Walking over, he saw a figure slumped in much the same position, head resting on the seawall, feet crossed. Now, though, the body was cold. There were no marks of any sort of violence. A half-smoked cigarette was lying on the man’s collar, as though it had fallen from his mouth.

The body reached the Royal Adelaide Hospital three hours later. There Dr. John Barkley Bennett put the time of death at no earlier than 2 a.m., noted the likely cause of death as heart failure, and added that he suspected poisoning. The contents of the man’s pockets were spread out on a table: tickets from Adelaide to the beach, a pack of chewing gum, some matches, two combs and a pack of Army Club cigarettes containing seven cigarettes of another, more expensive brand called Kensitas. There was no wallet and no cash, and no ID. None of the man’s clothes bore any name tags—indeed, in all but one case the maker’s label had been carefully snipped away. One trouser pocket had been neatly repaired with an unusual variety of orange thread.

The unknown man found on Somerton Beach. Investigators have commented that the man’s features, photographed sometime after death, give a misleading impression of his appearance in real life.

By the time a full autopsy was carried out a day later, the police had already exhausted their best leads as to the dead man’s identity, and the results of the postmortem did little to enlighten them. It revealed that the corpse’s pupils were “smaller” than normal and “unusual,” that a dribble of spittle had run down the side of the man’s mouth as he lay, and that “he was probably unable to swallow it.” His spleen, meanwhile, “was strikingly large and firm, about three times normal size,” and the liver was distended with congested blood.

In the man’s stomach, pathologist John Dwyer found the remains of his last meal—a pasty—and a further quantity of blood. That too suggested poisoning, though there was nothing to show that the poison had been in the food. Now the dead man’s peculiar behavior on the beach—slumping in a suit, raising and dropping his right arm—seemed less like drunkenness than it did a lethal dose of something taking slow effect. But repeated tests on both blood and organs by an expert chemist failed to reveal the faintest trace of a poison. “I was astounded that he found nothing,” Dwyer admitted at the inquest. In fact, no cause of death was found.

The body displayed other peculiarities. The dead man’s calf muscles were high and very well developed; although in his late 40s, he had the legs of an athlete. His toes, meanwhile, were oddly wedge-shaped. One expert who gave evidence at the inquest noted:

I have not seen the tendency of calf muscle so pronounced as in this case…. His feet were rather striking, suggesting—this is my own assumption—that he had been in the habit of wearing high-heeled and pointed shoes.

Perhaps, another expert witness hazarded, the dead man had been a ballet dancer?

All this left the Adelaide coroner, Thomas Cleland, with a real puzzle on his hands. The only practical solution, he was informed by an eminent professor, Sir Cedric Stanton Hicks, was that a very rare poison had been used—one that “decomposed very early after death,” leaving no trace. The only poisons capable of this were so dangerous and deadly that Hicks would not say their names aloud in open court. Instead, he passed Cleland a scrap of paper on which he had written the names of two possible candidates: digitalis and strophanthin. Hicks suspected the latter. Strophanthin is a rare glycoside derived from the seeds of some African plants. Historically, it was used by a little-known Somali tribe to poison arrows.

More baffled than ever now, the police continued their investigation. A full set of fingerprints was taken and circulated throughout Australia—and then throughout the English-speaking world. No one could identify them. People from all over Adelaide were escorted to the mortuary in the hope they could give the corpse a name. Some thought they knew the man from photos published in the newspapers, others were the distraught relatives of missing persons. Not one recognized the body.

By January 11, the South Australia police had investigated and dismissed pretty much every lead they had. The investigation was now widened in an attempt to locate any abandoned personal possessions, perhaps left luggage, that might suggest that the dead man had come from out of state. This meant checking every hotel, dry cleaner, lost property office and railway station for miles around. But it did produce results. On the 12th, detectives sent to the main railway station in Adelaide were shown a brown suitcase that had been deposited in the cloakroom there on November 30.

The staff could remember nothing about the owner, and the case’s contents were not much more revealing. The case did contain a reel of orange thread identical to that used to repair the dead man’s trousers, but painstaking care had been applied to remove practically every trace of the owner’s identity. The case bore no stickers or markings, and a label had been torn off from one side. The tags were missing from all but three items of the clothing inside; these bore the name “Kean” or “T. Keane,” but it proved impossible to trace anyone of that name, and the police concluded–an Adelaide newspaper reported–that someone “had purposely left them on, knowing that the dead man’s name was not ‘Kean’ or ‘Keane.’ ”

The remainder of the contents were equally inscrutable. There was a stencil kit of the sort “used by the Third Officer on merchant ships responsible for the stenciling of cargo”; a table knife with the haft cut down; and a coat stitched using a feather stitch unknown in Australia. A tailor identified the stitchwork as American in origin, suggesting that the coat, and perhaps its wearer, had traveled during the war years. But searches of shipping and immigration records from across the country again produced no likely leads.

The police had brought in another expert, John Cleland, emeritus professor of pathology at the University of Adelaide, to re-examine the corpse and the dead man’s possessions. In April, four months after the discovery of the body, Cleland’s search produced a final piece of evidence—one that would prove to be the most baffling of all. Cleland discovered a small pocket sewn into the waistband of the dead man’s trousers. Previous examiners had missed it, and several accounts of the case have referred to it as a “secret pocket,” but it seems to have been intended to hold a fob watch. Inside, tightly rolled, was a minute scrap of paper, which, opened up, proved to contain two words, typeset in an elaborate printed script. The phrase read “Tamám Shud.”

The scrap of paper discovered in a concealed pocket in the dead man’s trousers. ‘Tamám shud’ is a Persian phrase; it means ‘It is ended.’ The words had been torn from a rare New Zealand edition of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Frank Kennedy, the police reporter for the Adelaide Advertiser, recognized the words as Persian, and telephoned the police to suggest they obtain a copy of a book of poetry—the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. This work, written in the twelfth century, had become popular in Australia during the war years in a much-loved translation by Edward FitzGerald. It existed in numerous editions, but the usual intricate police enquiries to libraries, publishers and bookshops failed to find one that matched the fancy type. At least it was possible, however, to say that the words “Tamám shud” (or “Taman shud,” as several newspapers misprinted it—a mistake perpetuated ever since) did come from Khayyam’s romantic reflections on life and mortality. They were, in fact, the last words in most English translations— not surprisingly, because the phrase means “It is ended.”

Taken at face value, this new clue suggested that the death might be a case of suicide; in fact, the South Australia police never did turn their “missing person” enquiries into a full-blown murder investigation. But the discovery took them no closer to identifying the dead man, and in the meantime his body had begun to decompose. Arrangements were made for a burial, but—conscious that they were disposing of one of the few pieces of evidence they had—the police first had the corpse embalmed, and a cast taken of the head and upper torso. After that, the body was buried, sealed under concrete in a plot of dry ground specifically chosen in case it became necessary to exhume it. As late as 1978, flowers would be found at odd intervals on the grave, but no one could ascertain who had left them there, or why.

In July, fully eight months after the investigation had begun, the search for the right Rubaiyat produced results. On the 23rd, a Glenelg man walked into the Detective Office in Adelaide with a copy of the book and a strange story. Early the previous December, just after the discovery of the unknown body, he had gone for a drive with his brother-in-law in a car he kept parked a few hundred yards from Somerton Beach. The brother-in-law had found a copy of the Rubaiyat lying on the floor by the rear seats. Each man had silently assumed it belonged to the other, and the book had sat in the glove compartment ever since. Alerted by a newspaper article about the search, the two men had gone back to take a closer look. They found that part of the final page had been torn out, together with Khayyam’s final words. They went to the police.

The dead man’s copy of the Rubaiyat, from a contemporary press photo. No other copy of the book matching this one has ever been located.

Detective Sergeant Lionel Leane took a close look at the book. Almost at once he found a telephone number penciled on the rear cover; using a magnifying glass, he dimly made out the faint impression of some other letters, written in capitals underneath. Here, at last, was a solid clue to go on.

The phone number was unlisted, but it proved to belong to a young nurse who lived near Somerton Beach. Like the two Glenelg men, she has never been publicly identified—the South Australia police of 1949 were disappointingly willing to protect witnesses embarrassed to be linked to the case—and she is now known only by her nickname, Jestyn. Reluctantly, it seemed (perhaps because she was living with the man who would become her husband), the nurse admitted that she had indeed presented a copy of the Rubaiyat to a man she had known during the war. She gave the detectives his name: Alfred Boxall.

At last the police felt confident that they had solved the mystery. Boxall, surely, was the Unknown Man. Within days they traced his home to Maroubra, New South Wales.

The problem was that Boxall turned out to be still alive, and he still had the copy of the Rubaiyat Jestyn had given him. It bore the nurse’s inscription, but was completely intact. The scrap of paper hidden in the dead man’s pocket must have come from somewhere else.

It might have helped if the South Australia police had felt able to question Jestyn closely, but it is clear that they did not. The gentle probing that the nurse received did yield some intriguing bits of information; interviewed again, she recalled that some time the previous year—she could not be certain of the date—she had come home to be told by neighbors than an unknown man had called and asked for her. And, confronted with the cast of the dead man’s face, Jestyn seemed “completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance she was about to faint,” Leane said. She seemed to recognize the man, yet firmly denied that he was anyone she knew.

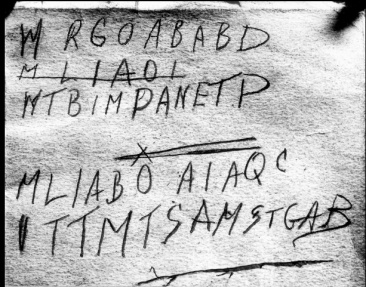

That left the faint impression that Sergeant Leane had noticed in the Glenelg Rubaiyat. Examined under ultraviolet light, five lines of jumbled letters could be seen, the second of which had been crossed out – and then apparently repeated two lines down. The first three lines were separated from the last two by a pair of straight lines with an ‘x’ written over them. It seemed that they were some sort of code.

Breaking a code from only a small fragment of text is exceedingly difficult, but the police did their best. They sent the message to Naval Intelligence, home to the finest cipher experts in Australia, and allowed the message to be published in the press. This produced a frenzy of amateur codebreaking, almost all of it worthless, and a message from the Navy concluding that the code appeared unbreakable:

From the manner in which the lines have been represented as being set out in the original, it is evident that the end of each line indicates a break in sense.

There is an insufficient number of letters for definite conclusions to be based on analysis, but the indications together with the acceptance of the above breaks in sense indicate, in so far as can be seen, that the letters do not constitute any kind of simple cipher or code.

The frequency of the occurrence of letters, whilst inconclusive, corresponds more favourably with the table of frequencies of initial letters of words in English than with any other table; accordingly a reasonable explanation would be that the lines are the initial letters of words of a verse of poetry or such like.

And there, to all intents and purposes, the mystery rested. The Australian police never cracked the code or identified the unknown man. Jestyn died a few years ago without revealing why she had seemed likely to faint when confronted with a likeness of the dead man’s face. And when the South Australia coroner published the final results of his investigation in 1958, his report concluded with the admission:

I am unable to say who the deceased was… I am unable to say how he died or what was the cause of death.

‘Jestyn,’ the nurse at the heart of the mystery, with her son – whom she would enrol in dance classes and who would go on to become a professional ballet dancer.

In recent years, though, the Tamám Shud case has begun to attract new attention. Amateur sleuths have probed at the loose ends left by the police, solving one or two minor mysteries but often creating new ones in their stead. And two especially persistent investigators—retired Australian policeman Gerry Feltus, author of the only book yet published on the case, and Professor Derek Abbott of the University of Adelaide—have made particularly useful progress. Both freely admit they have not solved mystery—but let’s close by looking briefly at the remaining puzzles and leading theories.

First, the man’s identity remains unknown. It is generally presumed that he was known to Jestyn, and may well have been the man who called at her apartment, but even if he was not, the nurse’s shocked response when confronted with the body cast was telling. Might the solution be found in her activities during World War II? Was she in the habit of presenting men friends with copies of the Rubaiyat, and, if so, might the dead man have been a former boyfriend, or more, whom she did not wish to confess to knowing? Abbott’s researches certainly suggest as much, for he has traced Jestyn’s identity and discovered that she had a son. Minute analysis of the surviving photos of the Unknown Man and Jestyn’s child reveals intriguing similarities. Might the dead man have been the father of the son? If so, could he have killed himself when told he could not see them?

Gerry Feltus, a retired Adelaide homicide detective, has spent years investigating the mystery of the Somerton man.

Those who argue against this theory point to the cause of the man’s death. How credible is it, they say, that someone would commit suicide by dosing himself with a poison of real rarity? Digitalis, and even strophanthin, can be had from pharmacies, but never off the shelf—both poisons are muscle relaxants used to treat heart disease. The apparently exotic nature of the death suggests, to these theorists, that the Unknown Man was possibly a spy. Alfred Boxall had worked in intelligence during the war, and the Unknown Man died, after all, at the onset of the Cold War, and at a time when the British rocket testing facility at Woomera, a few hundred miles from Adelaide, was one of the most secret bases in the world. It has even been suggested that poison was administered to him via his tobacco. Might this explain the mystery of why his Army Club pack contained seven Kensitas cigarettes?

Far-fetched as this seems, there are two more genuinely odd things about the mystery of Tamám Shud that point away from anything so mundane as suicide.

The first is the apparent impossibility of locating an exact duplicate of the Rubaiyat handed in to the police in July 1949. Exhaustive enquiries by Gerry Feltus at last tracked down a near-identical version, with the same cover, published by a New Zealand bookstore chain named Whitcombe & Tombs. But it was published in a squarer format.

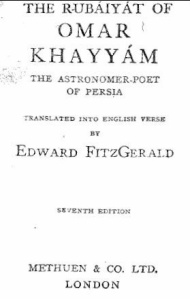

Add to that one of Derek Abbott’s leads, and the puzzle gets yet more peculiar. Abbott has discovered that at least one other man died in Australia after the war with a copy of Khayyam’s poems close by him. This man’s name was George Marshall, he was a Jewish immigrant from Singapore, and his copy of the Rubaiyat was published in London by Methuen— a seventh edition.

The Rubaiyat discovered by the body of George Marshall – an edition that should not, apparently, exist.

So far, so not especially peculiar. But inquiries to the publisher, and to libraries around the world, suggest that there were never more than five editions of Methuen’s Rubaiyat—which means that Marshall’s seventh edition was as nonexistent as the Unknown Man’s Whitcombe & Tombs appears to be. Might the books not have been books at all, but disguised spy gear of some sort—say one-time code pads?

Which brings us to the final mystery. Going through the police file on the case, Gerry Feltus stumbled across a neglected piece of evidence: a statement, given in 1959, by a man who had been on Somerton Beach. There, on the evening that the Unknown Man expired, and walking toward the spot where his body was found, the witness (a police report stated) “saw a man carrying another on his shoulder, near the water’s edge. He could not describe the man.”

At the time, this did not seem that mysterious; the witness assumed he’d seen somebody carrying a drunken friend. Looked at in the cold light of day, though, it raises questions. After all, none of the people who saw a man lying on the seafront earlier had noticed his face. Might he not have been the Unknown Man at all? Might the body found next morning have been the one seen on the stranger’s shoulder? And, if so, might this conceivably suggest this really was a case involving spies—and murder?

Sources

‘Body found on Somerton Beach.’ The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA), 2 December 1948; ‘Somerton beach body mystery.’ The Advertiser, 4 December 1948; ‘Unknown buried.’ Brisbane Courier-Mail, 15 June 1949; GM Feltus. The Unknown Man: A Suspicious Death at Somerton Beach. Privately published: Greenacres, South Australia, 2010; Dorothy Pyatt. “The Somerton Beach body mystery.” South Australia Police Historical Society Hue & Cry, October 2007; Derek Abbott et al. World search for a rare copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Accessed 4 July 2011; Graeme Wood. “The lost man.” The California Sunday Magazine, 5 June, 2015, accessed 6 June 2015.

That’s absolutely fascinating. Thanks so much for posting it here, Mike.

[…] Truly wonderful piece on a mysterious corpse in 1948 Australia. Poison, spies, codes, Omar Khayyam […]

I first read about this a year or so ago, but this article was much more in-depth. Thanks for sharing, reading it gave me the shivers.

Very interesting case! I wonder if this whole thing was an Isreali thing – sounds very similar to the complexity and bizarness that the Isrealis like to do when they were rounding up and killing ex Nazis.

If I know anything about obsessed historical researchers, I suspect that they will trace this comment to me and interview me about my whereabouts on the night of Nov., 30, 1948. I was born in the 80s, that’s my alibi.

A likely story frugaldutchman.

You are probably not even frugal… or dutch… or a man.

I smell a box office hit!

Not for hollywood. If the stars don’t like each other then get married, they won’t make it.

[…] Possibly the most bizarre unsolved mystery I’ve ever heard about: The Body on Somerton Beach […]

Fascinating. Would make a great movie…especially if there was a proper ending.

I figure from the labels being taken out of his jacket and the oddity of the book he was probably a spy of some type but still….

I’m pretty sure that’s Harvey Keitel.

“He was lolling about 20 yards from them…”

In this age of teh intertubes, surely the author could have picked a word that didn’t evoke something completely uncharacteristic…

Somebody in Russia knows (or knew).

If he was a Russian agent, why would he write a coded message in English? Also, he smoked English sigs. and had American clothes. Look at his toes and calf muscles, they do tell you something! I crunched the book on the chance that it was a “one-time-pad” and decoding the cipher showed he definitely was a spy but for whom is the big mystery?

Spies work in different languages. They usually are fluent in several depending on their role.

Just because he worked for Russia wouldn’t mean he didn’t communicate in English.

In fact his job would demand it if he were operating in an English speaking country. He could hardly be expected to walk around speaking Russian while on job in Australia.

English cigs, American clothes would be part of his cover. He would have those things so he fit in, you know didn’t look Russian

Still fascinating. Did they ever exhume the guy? What about DNA testing, comparing his to the “son” who is presumably still alive?

Oh, I see on Wikipedia that the son died too, a couple of years ago. Still…

I am fascinated by the idea of spy code books disguised as real books of unlikely editions. That is incredibly cool. Why the Rubaiyat? It poses all sorts of question: a book common enough to not be suspicious, but not too common or someone might notice the differences. I wonder what the perfect book would be for that purpose these days?

I wonder what the perfect book would be for that purpose these days?

The Bible. Nobody actually reads it.

Great post!

Abbott has discovered that at least one other man died in Australia after the war with a copy of Khayyam’s poems close by him. This man’s name was George Marshall, he was a Jewish immigrant, and his copy of the Rubaiyat was published in London by Methuen— a seventh edition.

Man, this is so frustrating. A Jewish immigrant from where? I see this quite a bit: “a Jewish immigrant,” and I’ll never understand it. It’s as though the described people are immigrants from the Land of Jew. Oh, hey, journalist: it seems like you are trying to convey at least some rudimentary information, yet you overlook the most fundamental basic context? Where is your brain? gah.

Anyway, this particular dead guy looks like my maternal grandfather – enough to have been him* (or, say, his brother-who-looks-very-very-much-like-him), and my grandfather was the child of German immigrants to the U.S.

It certainly seems extremely likely that the war and spycraft had something to do with this: exotic poisons, cyphers, snipped labels, apparent multiple copies of a particular book that doesn’t exist, WWII nurse who apparently had a habit of passing out such books. A real-life potboiler!

* If someone had told me it was an old photo of my grandfather sick or passed out, I wouldn’t have argued – but my grandfather died in the ’80s

Fascinating case.

I’m disappointed that the release of the Mitrokhin Archive didn’t wrap this up for us. Assuming Vasili Mitrokhin is legit, this surely should have merited a mention if there was any involvement on the part of the Soviets.

For those of who don’t have FaceBook accounts, what are the “intriguing similarities” with Jestyn’s child?

Haven’t we all seen enough movies to see that this clearly was some kind of spy thing?

What a surprise it is unsolved…

The timeline leading up to the Somerton Man incident is fascinating:

1945 June 3rd, “George” Joseph Saul Haim Marshall (aged 34) was found dead of poisoning in Mosman, Sydney. It was believed to be a suicide. A copy of Omar Khayyam was found open next to his body. Mosman is between St. Leonard’s where Jestyn lived and Clifton Gardens where she later met Boxall. The estimated date of death was May 21st, 1945.

1945 August, Jestyn gives Alf Boxall an inscribed copy of the Rubaiyat over drinks at the Clifton Gardens Hotel, Sydney.

1945 September, Alf Boxall sent to military service (Cairns, Port Moresby, Bougainville)

1945 November 11th, Jestyn completes nurse training course at the Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW

1946 October 18th, Alf Boxall returns to Australia from military service.

1946 December 31st, Alf Boxall is detached to the Services Training Centre in NSW.

1947 February, Alf Boxall is discharged from military service.

1947 April, Under Operation Venona, American cryptanalysts, at the US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service, crack messages transmitted from the Russian Embassy in Canberra to Moscow. They detected leaked intelligence information, and this results in a ban of US classified information in Australia during 1948.

1947 July, Jestyn’s son is born.

1948 May, Sir Percy Sillitoe, Director General of MI5 flys to Australia and prime minister Ben Chifley is informed of the security breach.

1948 August 16th, US Assistant Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White, died suddenly of a reported digitalis overdose. He had been identified as a spy under Operation Venona.

1948 November 30th, the Somerton Man presumably arrives in Adelaide by train sometime between 8:30am and 10:54am.

It’s such an interesting but ultimately frustrating case with the lack of investigation into Jestyn, when everything appears to center around her.

For those of who don’t have FaceBook accounts, what are the “intriguing similarities” with Jestyn’s child?

It’s really worth reading the Wikipedia page as the account is quite good (and much fuller than just a couple of years ago). Jestyn’s child appears to share not one but two rare physical abnormalities with Somerton Man: a malformation of the ear and the lack of certain teeth.

paging Tim Powers!

I find it very puzzling that Jestyn’s name has never been released. Given that her apparent surname is out there, and that at least some investigators have photos of her son, it should be trivial for someone to be able to track her down given all the info (approx address, phone number, date of marriage, etc.) that is out there.

There is something really weird with what I just read. (Yeah, you’re probably saying: “No shit, Sherlock!”)

Let’s take a look at the chain of events:

A guy has his car parked by the beach.

Mystery man dies on the beach.

Guy takes his car from the beach for a drive. Book is found in the back of the car.

“Tamam Shud” is found in the fob pocket of the Mystery man’s pants.

Guy notices the book in the back of the car. It has the words “Tamam Shud” missing from the end.

Cop finds number and code (or maybe Arabic writing or something) in the book.

Woman whose phone number it is says she gave book to a guy who is still alive and has the book intact.

Woman claims to not know the dead Mystery man but she almost faints at seeing a cast of his face.

BUT

The book that was found in the car did have the nurse’s number on it. So there’s the weird thing about it. I don’t know. Seems relevant somehow.

This was a great read. True mystery seems rare these days.

@ anastasiav, Jestyn’s real name is possible to find out (although not easy) and most of the more obsessive dedicated sleuthers on the case know it. Not making it public is a courtesy to her surviving relatives, who are apparently going through some very rough times and don’t need a camera crew turning up on their doorstep.

@ Gator, the author of the book on the case has some info on his website stating that the Attorney General has refused an application from another party to exhume the unknown man. I suspect at this stage it would only be granted to the potential relatives or other people who can prove a need to know.

The story of the Somerton Man is what inspired me to leave a piece of paper with a bunch of Zodiac-style characters on it in my wallet. That way if I happen to die on the side of a road somewhere, people will think, “poor sumbitch, got drunk and wandered into the street,” but they’ll discover the paper and say, “ZOMG, he’s a spy, IT MUST BE MURDER CALL ANDERSON COOPER” and a fuss will be made about me for decades.

You, sir, are a genius.

This blog and beachcombing have added a bit of classy mystery and intrigue to my otherwise (these days at least( depressing rss reader.

I am fascinated by the idea of spy code books disguised as real books of unlikely editions. That is incredibly cool. Why the Rubaiyat? It poses all sorts of question: a book common enough to not be suspicious, but not too common or someone might notice the differences. I wonder what the perfect book would be for that purpose these days?

I’m fascinated by this too, and I enjoyed pondering the “perfect book” question while I did dishes. The most interesting thing I could come up with was a Mad Libs book with the code disguised as the words on the filled-in blanks, written in bubbly tween-girl-at-a-slumber-party handwriting.

I’d start off by assuming the cops back in 1948 weren’t idiots, and had basically the same sort of skills and instincts as cops today. If that’s so, the lead which screamed at them for followup, is that “Jestyn,” in claiming not to know the victim, was obviously lying. That sort of a lead is red meat to today’s cops. A live witness that you know is concealing information? They’d go at that woman hard, over and over. So, I think, would the cops of 1948. If they didn’t, I wonder why, and the first answer that springs to my mind is that they were damn well told not to. Too bad that the people in a position to speak to that possibility are also long since dead.

If they didn’t, I wonder why, and the first answer that springs to my mind is that they were damn well told not to.

Indeed, but as this hasn’t come to light in any of the regular document declassification hand outs after both 30 and 50 years have expired, it might be buried so deep we will never know.

Good read.

holy shit that’s insane…anyone have any theories?

The poison, the lack of clothing labels, and the book are all bloody fascinating.

Not many people poison themselves with really rare poisons; why would? Rare poisons are used by assassins and murderers, to make their identification harder. It suggests that if the man was murdered, the killer wanted to make identifying his cause of death difficult, which it is.

The lack of clothing labels is bizarre. It does make it harder to identify you, which is something a spy or criminal would want to do.

The book is very strange though. We don’t know the provenance of the book the police recieved from the Glenelg man. It is very strange that it should lead to the nurse, who directed them to Boxall, but who is alive. That the book was found, reportedly, in their car with the page removed is also strange. But I worry about that book; how do we know the men didn’t make it all up, scrawl the code themselves, as well as Jestyn’s number? That would be why the lead to her and Boxall went nowhere.

The other man though, who died with the Methuen edition that doesn’t exist. That is really interesting. A copy of an edition that doesn’t exist is a great cipher; proof to another spy you are who claim to be, because you have something subtley unique.

But then again, it could just be a suicide. “It is ended” is a rather final statement about your life to carry in your pocket.

well, most people seem to point to the words “it is ended” as a suicide note, but on the other hand, could it not be a message left by an employed to an employer that the work is done, the task has ended, or the ‘hired job to bring death to another’ being completed?

I think he def was some sort of spy. I don’t want to say anything terrible about a guy who’s identity is unknown and is dead, but I almost feel like he raped the nurse…it’s also interesting how a nurse knew him. Maybe he was injured and stayed in her hospital for some time? I also feel the need to incorporate the fact he wore heels..maybe he did some spy type work as a woman, which might also explain some of the shock of the nurse. What doesn’t make much sense is why she wouldn’t say anything…I think he was murdered and perhaps the statement in his pocket was a message the murderer put there for someone else to find out. this whole story is so interesting. I really want someone to figure it out. Too bad they didn’t run a DNA test on the man and then the son of the nurse.

I think it’s more likely she had worked with the man while in drag and didn’t realize he was a man only to suffer the shock of the bust and realizing that she had been tricked this whole time.

She may have learned or known he was up to something nefarious and thus had to keep her silence but realized at that point the secret she knew was in fact a cover up…

you see, I wondered that but the thing is she recognized him instantly…if he had worked with her in drag I feel it would have taken a few moments for the recognition to sink in.

The lack of clothing labels is bizarre. It does make it harder to identify you, which is something a spy or criminal would want to do.

Is it normal for adults to write their name on their clothes tags in Australia? It would seem if you were a spy you would not write anything on the cltohes tags unless it would be seen as strange not to.

But I worry about that book; how do we know the men didn’t make it all up, scrawl the code themselves, as well as Jestyn’s number?

I would assume at the very least that the officers matched the torn portion to the torn page… faking a tear on a piece of paper you have presumeably never seen is a tricky feat…

But then again, it could just be a suicide. “It is ended” is a rather final statement about your life to carry in your pocket.

It seems the guy may have been decent with a needle if his ownership of the orange thread indicates that he fixed his own pocket, but it seems like an odd way to hide your suicide note. Aren’t suicide notes usually meant to be found? It seems quite possible that one would go forever unoticed.

That said I suppose it could carry a personal value more than the need to convey a message to people after you die….

I don’t always commit suicide, but when I do you’ll be baffled.

The nurse was shocked because she was having an affair with this man, and he was still corresponding with her – even after he died. The assassin who killed him knew about the relationship, and continued writing on the behalf of the dead man so as not to raise suspicion.

Apparently, she wasn’t very creative, since she was handing out copies of the same book to all her men.

I’ll think of more…

I love this one, because it helps my belief that Australians are basically a tolerant lot. Bloke in a suit dying on a beach, using his last strength to reach out to passers-by, and they all think “Oh, he’s just a bit pissed, we’ll let him be..”

[…] Many thanks to the brilliant @thebrowser for drawing our attention to this brilliantly eerie article.[…]

That was absolutely fascinating to read. Wonder if it’ll ever be solved?

you kind of think not – echoes of Zodiac killer, though even more baffling

My first impressions of this case:

* He appears Russian, perhaps Jewish. A Soviet wartime spy?

* Clothing labels removed is SOP for covert operations.

* No ID is also SOP for covert operations.

* Nurse Jestyn was clearly familiar with the deceased and was privy to his identity.

* His Rubaiyat copy appears to be a spy tool, not a genuine book.

* Indecipherable codes written in the Rubaiyat.

With these facts alone, one could conclude that he was a spy possibly seeking to re-connect with his old contact (Jestyn) for unknown reasons. He was promptly liquidated in the process by someone in government intelligence with access to rare poisons which would hide their crime.

Just my take!

I really need someone to solve this now please, I need closure!

[…] Un article à lire absolument si vous aimez les histoires de détectives! […]

I was just reading about the Tamam Shud case during a recent conspiracy-theory obsession sparked by the D.B. Cooper publicity of late. I find it fascinating. I hope it’s solved eventually, though I’m obviously not holding out a lot of hope.

This is amazing. I love mysteries like this. Bits of remind me of Twin Peaks.

Might track down a copy of the book about the case.

There are a lot of people who have spent a lot of time investigating this thing themselves.

The most plausible explanation seems to be that it’s something to do with spying, though – the connection with the other guy who died with another copy of the same book, but they were both editions which *didn’t exist*, is pretty indicative of something shady…

Can someone sum it up in a paragraph or two…

for those of us who can’t be arsed reading for an hour or so?

Australia, 1948.

Man is found on a beach, dead. Immaculately dressed. Labels cut out of clothes, only possessions a one-way ticket from Adelaide and a piece of paper torn out of an extremely rare edition of a book of Persian poetry – the final line of the book, which translates as, “It Has Ended.” He has certain physical attributes which are very unusual, but no other identifying features. No obvious cause of death, nor indication whether it was suicide or murder.

Police search around and find a train station locker with a suitcase in it, deposited the day before the man died. Contains strange items (knife without a handle, sheet of zinc, etc.) but nothing to identify the man other than a ball of thread which had been used to sew up a hole in the pockets of the suit he was found wearing.

Then someone came forward and said they found a copy of the book of Persian poetry that the note was ripped from in the back of their car – they had assumed their brother-in-law had left it there. In the book the page had been torn out, and there was a phone number for a woman called Jestyn. The police spoke to Jestyn and she said she had given a copy of that book to a man she had known during the war, a guy called Alfred Boxall. The police went to Afred’s house and he was alive and well, and still had the book of poetry with her inscription in it.

It’s also the only other known copy of the specific edition of that book of poetry. The police eventually tracked down the edition to a small independent bookstore in New Zealand who had put it out during the war, but none of their editions was the shape and size of the two the police had found – despite the fonts and layouts being identical.

Then the police found indentations of writing on the first book of poetry, the one with the page missing. Examining it they uncover five lines of letters which seem to indicate some kind of obvious code, but despite sending it to military codebreakers around the world, to this day nobody has managed to crack it.

The case it still unsolved.

Could it not just be that he commited suicide and the stuff with the book in the third paragraph there is either mischief-making or completely coincidental?

Could be.

Some private investigators who have taken a person interest in this over the years have pointed out that the woman’s son – born when she was with another man – bears a striking resemblance to the dead man. And, when shown a photo of him, she reacted with shock and surprise, but then refused to say that she knew him when it was pretty clear she did. So some people think that she, or someone she knew, bumped him off, as maybe this guy was going to expose their affair.

But in that case there are just so many weird extra little facts. Like, the woman was a nurse in the war, and had connections to a local military base which is known as a sort of Australian Area 51. Cutting the labels out of clothing is standard procedure for undercover agents. The other man she sent the book of poetry to, Alfred, lived in the same town as the national zinc mining corporation (now known as Rio Tinto), and the guy had a sample sheet of zinc in the suitcase at the train station. And, most intriguingly, there was a case of a Jewish man dying in Malaysia around the same time – one of the only things he had on him was… the same book of Persian poetry, and it was also an edition which didn’t actually exist. The police called up the publisher in England to ask about it and they said they’d never gone beyond a fifth edition, but the one the Jewish guy had stated it was the seventh edition in the front. It seems that, at that time, that particular book was used as some kind of code or cipher book – which would also explain the mysterious letters in the back of the dead man’s copy.

Then there’s the third theory, that he killed himself because he was a closet transvestite and his secret was discovered. The coroner noted he had unusually well-developed calves, like someone who wears high heels often, and he had a slightly-faded tan running up his legs, ending just below his groin. His physique, in general, was that of a ballet dancer, or a competitive swimmer, the coroner said. Very good shape for a man in his 40s, but at the same time, not entirely sure what activities he would have done regularly to sculpt his body in such a way.

This is Crazy.

in other news, you should read The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (The book the page was torn from) It’s beautiful.

I never heard of this when I was growing up there. What is it with Adelaide??

RT @brainpicker: Behold one of the world’s most perplexing cold cases, circa 1948 http://j.mp/r6pV7G -Most fascinating true crime ever!

That’s just a bit unsettling living here in Adelaide, South Australia. Some weird things like this do go on!

“He still has no identity or real cause of death…”

For something that happened in 1948, I don’t expect any new evidence to come up.

You never know. Government docs sometimes get declassified. Could this be an early cia hit on a Russian spy? That might explain why the victim was untraceable and method of killing unidentifiable.

I think it’s pretty safe to say that he was a spy for someone.

This is a mostly solved case for those in the know, but there are still some puzzling elements left to figure out. It turned out to be pretty much what you might expect in the cold war era, with the Rosenburgs, russian / jewish spies etc. Don’t stress too much about it.

[…] The “Mystery of the Somerton Man”, or “The Taman Shud Case”, where the body of an unidentified male was found on Somerton beach, near Adelaide, capital of South Australia, in December 1948 remains one of Australia’s most perplexing unsolved “missing persons” cases […]

This is a must-read story. Straight outta Hollywood.

Crazy story but it most likely will never be solved. Shame

mannnn.i’m not usually lazy…and I will attempt to read this…but..IT BETTER BE GOOD!

Fascinating. There’s a lot of stuff on YouTube about this. Seems like they’ll never know unless someone is still alive to step forward

Crazy. It’s too bad they weren’t able to question her any further about this. She had to know something.

Crazy read, I’m actually interested especially about the fact there was a seventh edition of a book that doesn’t exist.

Good read. That chick definitely knew something.

So how did that Glenelg man and the Brother-in-Law obtain that book?

It just magically appeared in back seat of his car? Were they even questioned?

Too many questions. Pretty good story though.

Wow that was an awesome story…i actually read all of it

Lot’s of weird, unanswered questions though.

Like Max said, why was the book in the back of the mens car?

What does the code say?

What’s the significance of the orange thread?

7th Rubaiyat and only 5 copies were released?

Why did the unknown man wear high heels?

Why did Jestyn almost faint when shown the picture of the man, what was the connection there?

So far, it seems like the most logical thing was he was poisoned through the tobacco in his cigarettes like stated.

Damn

I’ve read about this before, and I assume it was a result of Cold War espionage.

It was a crazy time back then.

As crazy as this story sounds, I bet they’re a bunch of intelligence officers in the know laughing at the attention this story gets.

Imagine if it was a just a bunch of spies trolling on some, “Hey, you know that dude we have to take care of, what if…”, shenanigans ensue.

that was nuts…awesome story OP, thanks. That nurse knew something… I can see Dicaprio starring in this if it makes it to Hollywood.

As who? A dead guy or a detective? This was most def a good read.

I was thinking about that…obvious choice would be a detective. They could come up with some sort of story for the “unknown man” and run with it from that angle but that would take the mystery out of it. If they did choose to give the unknown a story they could have two stories (“unkown man” going through whatever leads up to his death and the detective trying to solve the case) working out side by side throughout the film…

Man, I live in Adelaide and I’ve never even heard about this before.

Very interesting… but man, took me 15 minutes to read SMH

Probably a spy or con man something like that with no family etc. Probably was tied to some underground organization like the mafia, maybe he F’d up and had to kill himself.

He was probably a real smart guy, kept his identity hidden all the time.

“At least it was possible, however, to say that the words “Tamám shud” (or “Taman shud,” as several newspapers misprinted it—a mistake perpetuated ever since) did come from Khayyam’s romantic reflections on life and mortality. They were, in fact, the last words in most English translations— not surprisingly, because the phrase means ‘It is ended.'”

AAAAAAHHHHHH, my eyes just went watery and I got the most heinous chills!

TWO combs?!

@Ironic Hipster Meme What happens when you line up the smaller of the combs against the opening passage of the Rubayyat, and compare which tines line up with the code in the back?

…just kidding.

Also, the cut-off knife intrigues me. Will ponder this.

AH!I totally became obsessed with this when it showed up on Longreads recently! I feel for the nurse though, really. No one wants to get busted handing out the same book to every cute soldier she bangs.

@amuselouche yeah BUT how do you account for the fact that the edition found with him is unique and hasn’t been located anywhere else in the world? oh my God this is truly the weirdest case of all time.

@Ophelia RIGHT. Also – How did the book get into that car? Also – was he not definitely a Russian ballet dancer/ spy?

ALSO – I followed that link to see the striking similarities between the dead man and Jestyn’s son and didn’t see any photographs. What am I doing wrong? I want to see!

@elysian fields This is the part that twists my brain into little pretzels, too! To recap:

1. A rare edition of a book [B1] is found in a car the night of the murder, with a scrap of paper missing that matches the one in the dead man’s pocket.

2. In the back of B1 is written a phone number.

3. The woman to whom the phone number belongs admits to having owned said rare edition, but claims to have given it [B2] away several years before.

4. This claim is corroborated, the recipient of B2 is alive, and the book is intact.

Unanswered questions:

Just how rare was this edition?

How did the woman’s number get into the back of B1?

Who was the mysterious man who asked her neighbors about her?

Why did she appear “likely to faint” when shown a picture of the dead man, despite denying that she recognized him?

What am I missing?

@Vera Knoop Sure, she denied it, but her reaction indicates to me that she definitely knew him. The weirdest part to me is, as you mentioned, how her number got into the dead man’s book. It is suggested that his copy was manufactured specifically as some kind of espionage implement, hence its uniqueness; but again, why was her number in it? And why did she give another man a different copy (B2)? What is the connection between B1 and B2?

*mind implodes*

@elysian fields The one-time pad theory makes sense, though it seems weird and sloppy in that case that her phone number would just be in it, unencrypted. Also, wouldn’t a rare book be kind of conspicuous? You don’t want your spy equipment to be an object of desire for people who aren’t even in the game. Something like an oral hygiene pamphlet or tax brochure would be easier to sneak around, I’d think.

@Vera Knoop I have nothing to add except that the nurse is clearly the missing link. They should have interrogated the hell out of her. Maybe she was also a spy? And why didn’t the police show his likeness to her neighbors so they could figure out if he was the guy who came to visit her? Sloppiness around her role in things…maybe someone “higher up” told police to back off?

@hands_down Also agree that the nurse is the missing link, and I also totally wondered whether the reason they didn’t interrogate her is because someone asked them not to? Particularly if British handlers were also following this?

@Ophelia The theory that I just came up with is that the nurse was a middleman for the spies, basically to hand out these to books to whoever was supposed to have them, but nothing further than that. Which explains her shock when she saw the likeness.

@hands_down I’m from Adelaide. We’re a pretty small city (1 million inhabitants) and pretty far from anywhere. In the 50s, we were SO FAR FROM ANYWHERE and pretty parochial. I am not really surprised by the lack of interrogation – probably along the lines of ‘we can’t lean on her, she’s a lady! She’ll FAINT!’ If she presented as respectable, then she’d probably have her boundaries respected.

@Vera Knoop I dunno, that picture of the body on the wiki article is pretty creepy. If some detective came around asking me difficult questions and shoving that in my face, I might appear likely to faint too.

@Craftastrophies That’s helpful to know. I still think she was some sort of middle person for spies, but maybe she wasn’t interrogated for the reasons you laid out, not because of some shadowy Cold War conspiracy.

@amuselouche Which is why I’m going with the theory that it was a one-time pad.

The creepiest part for me was the guy who was also found to have died with a rare copy of this book near him, except his rare copy was a 7th edition, except the publisher never went beyond a 5th edition. CREEPS.

@Vera Knoop I dunno, that picture of the body is pretty creepy. If some detective came around asking me difficult questions and shoving that in my face, I might appear likely to faint too.=

Amazing story, pure Sherlock Holmes

[…] Creeping myself out by reading about the “Tamam Shud” case of the unknown body on a beach in Adelaide in the 40s […]

Fascinating! Like reading the aftermath of a spy novel, without the story itself. I bet this one gets solved when something gets declassified. Might the calf muscle development have come from scuba flippers?

Today is one of those “Mike Dash is the best reporter on the planet” days. If you don’t believe me, read this: http://long.fm/yU0Ppx

I am dorking out on this in a big way.

[…] I fell asleep reading this Australian unsolved mystery article and finished it the second I woke up this morning […]

Great unsolved mystery, great write-up

One of the strangest and most curious unsolved mysteries ever.

[…] esoteric poisons. rare books. unbroken codes. powerful calf muscles. “it is ended.” a very peculiar real mystery […]

there is an explanation, a theory, a linking of all the known facts, a story by actual timeline. why he died, who was there when he died, what were the circumstances that lead up to his death, and why his name was Kean(e)

[…] I’ve shared this once before, but here you go again. One of (in my opinion) the best stories I’ve read […]

This is so interesting I just have to share it omg.

This is self-serving I know, but amongst the fiction there are some facts not previously known, and some conclusions that could be argued. Starting with the fact that at least two men were involved in the actual killing on 30 Nov 1948.

http://tomsbytwo.wordpress.com/

Jestyn’s name was Jessica Ellen Harkness. She was born in Marrickville in 1921. Her son was Robin Thomson, born 1947 in Mentone, Victoria and she married Prosper McTaggart Thomson, the proprietor of Prestige Motors, Adelaide, in 1950. The names Teresa Powell and Prestige Johnson are pseudonyms, and it seems particularly stupid to persist with them since the parties are all dead.

There is a very interesting file in the NAA – it contains a transcript of all the takes made during the production of the 1978 TV program concerning the Somerton Man mystery (ABC report “Inside Story”. Interviewer Stuart Littlemore). Lionel Leane, Len Brown, Paul Lawson and others, were interviewed by Stuart Littlemore. The material is in the NAA. Search for “The Somerton Beach story” 1977 Series number C673. Item bar code 7937872.

There is much material that wasn’t used in the final cut of the program, and some of this material throws light on the SM mystery.

I have noted some of the interesting matters.

Page 40 – “…… chemist had his car parked in Jetty Road, Glenelg, near the Pier Hotel ….. discovered …. this book in his car – had been thrown into his car …. on the 30th November 1948.”

Page 44 – Brown believes that Lionel Leane “may have” the relevant copy of the Rubaiyat.

Page 44 – there were two phone numbers written on the back of the book. The first one is clearly Jestyn’s, and the second is a “business” (identified as a Bank in other documents).

Page 40 – “You rang them both? (phone numbers written on the back of the book). “Yes”.

“Both were Adelaide numbers?” “Yes” (Brown)

Page 45 – “… it’s most unusual” (taking a plaster cast). Brown said that this was the first time such a plaster cast had been used.

Page 51 – A strange reaction from Lawson. Who are the “them” that he and Stuart are referring to here? Why was it “tender ground”?

S – “did any of them think they knew him? (Somerton Man)

L – “I don’t know. By the way, you’re on tender ground (laughs).”

S – “Explain why?”

L – “Cut it boys.”

S – “Well don’t worry about them.”

L – “No, I/m not going on with that part of it.”

Page 61 – “I think that he suicided ….. suicide because back about 100 yards from where he was sitting on the seat, I found a hypodermic syringe.” Leane.

Page 62 – Stuart. “So what happened to the hypodermic syringe, do you remember?”

Leane “”It’s all down there in the place, still.” (from later in the interview “the place” he is referring to seems to be the police storage facility.)

Page 64 – “Police have it” (the hypodermic syringe). Leane

Page – 175 “…. destruction of the centres of the liver lobules.” I am surprised that this was not followed up. It indicates that SM had either suffered a significant infection/disease, or had previously been exposed to toxic materials. I remember (but can’t find the reference) that one of the pathologists (Dwyer?) commented that there was unusual pigment in the liver. It wasn’t the usual sort of pigment that comes from age, disease and exposure to usual toxic materials (such as alcohol), and the pathologist could not identify the cause of the unusual pigment (he ruled out malaria from memory). I am reminded that the pathologist also mentioned that SM’s pupils were irregular and of differing sizes. There are various diseases and injuries that can cause this, but nobody appears to have followed this up.

Page 157 – Patrick James Durham, the police photographer and finger print expert gave evidence regarding photographing and finger printing SM’s corpse. But, strangely in my view, Durham was not asked about photographing the “code” in the Rubaiyat. As I have mentioned previously, the images of the “code” clearly indicate that the writing was present only as indentations in the back cover of the Rubaiyat. This point is important because it indicates that the rear page was torn out before the book was apparently thrown away. The fact that Durham did not mention photographing or otherwise dealing with the “code” and telephone numbers possibly indicates that he was not directly involved in this aspect. But, if he wasn’t involved, who was, and why? Durham was the logical person to handle this sort of investigation. Perhaps the Rubaiyat was examined by some other group, and that is why the confusion (both infra-red and ultra-violet methods have been mentioned)? But the evidence clearly points to an oblique lighting technique to enhance indentations.

It has been pointed out on this site that the apparent loss or destruction of the physical evidence, and nearly all of the file material relating to this case, is unusual and suspicious. But there is a possible reason for this, and this reason, if it is indeed the reason, casts fresh light on the Somerton Man mystery.

In 1977 Justice James Michael White of the Supreme Court of South Australia was commissioned by the Premier, Don Dunstan, to report on the activities of the Special Branch, which was a semi-secret section of the SA police force detailed to conduct intelligence work on possible subversive activity.

Justice White’s report was extremely unfavourable regarding the activities of the Special Branch, and it was disbanded and the intelligence files destroyed (28,500 files according to one source).

So, is it just coincidence that nearly all the Somerton Man case material apparently disappeared about this time? If there is a connection, then it indicates that the Special Branch were involved in the Somerton Man investigation, and this would indicate that the police believed that there were security implications.

One way of discovering if this is the case, or not, is to look at the police involved in the case. Were any from the Special Branch? I don’t know, but it might be discoverable even though the identities of Special Branch officers were generally not made public.

During WW2 intelligence regarding subversive activity was handed to the military, but with the end of WW2 this responsibility was handed back to the South Australian police (ASIO did not start up until early 1949) who established a “Subversives Section” in 1947. This was re-named “Special Branch” in 1949.

Somehow stumbled across this article and it left me speechless. Mind blown.

[…] the possible murder case with more questions and less answers than LOST […]

Pingback: Somerton Man – the enduring Australian mystery | Graham's Blog

My favorite unsolved (although one can guess) mystery.

The two daughters of “Jestyn” (who’s real name has finally been revealed as Jessica Thomson), the nurse whom the Somerton Man seemed to know, have lodged a request for his exhumation, believing he may be their father. The family of their late half-brother (of unknown father!) have also done the same.

The daughters have revealed that they believe their mother was indeed a Soviet spy, and opine that this is how she knew the Somerton Man. In life, the now deceased Jestyn refused to tell them who he was, but did admit to them that she had lied to the police when she said she didn’t know him, and that the case is “above police level”.

Pingback: A che punto è la notte 15 – Venuti dal nulla

Interesting developments!

http://www.ciphermysteries.com/2016/03/26/margaret-alison-bean-alison-verco#comment-341976

I just wanted to let you know that I have a Taman Shud/Somerton Man Decoding on my website http://cosmicorderoftarot.com/taman-shud-decoding/ From what I translated, he was indeed a spy and the letters are mainly pseudo-military acronyms. For example, Line 1 of M/W RGOABABD is for Men/Woman Regimental (R) Ground (G) Operations (AB), Amphibious (AB) & Airborne Division (ABD). The Airborne Division’s usual acronym is ABD. On this line he’s indicating the American Army, and on Line 2 of MLIAOI is for Man (M) Liaison (LIA–abbreviation) Office (of) Intelligence (American). The other lines outline British and Australian military acronyms. It won’t take you long to review my decoding. I also have a Shugborough Decoding on my website if it all interested.

All the best, Waite of Cosmic Order of Tarot

[…] I’m aware that this has been posted before quite a while back, but the article itself is written rather well and talks a lot more in depth about the events relating to the mystery than the previous sources […]

Why apologize? It’s still a great story, and the WIkipedia article is not very interesting reading. As you note, this one is much better reading.

Pingback: TIL In 1948, A man was found dead on a beach in Adelaide and the words “Taman Shud”, torn from a book, in a hidden pocket. The rest of the book was found in a nearby car, with a mysterious code on a page only visible under UV Light. The code a

I doubt it’s some crazy conspiracy-like reason and maybe he went there as a kid, or was there during the war, or he met his love there, or something and it was just a place to that meant something to him. So he wanted to die there.

Or he just lost his mind. People lose their minds all the time.

Pingback: Quick Fact: In 1948, A man was found dead on a beach... - Quick Facts

Has Ted Cruz ever been to Adelaide?

i’m not saying Ted Cruz killed a man on a beach in Adelaide, Australia in 1948…Of course there’s no evidence that he did – but the worrying thing is that there’s absolutely no evidence whatsoever that he didn’t either – which begs the question, just exactly how long has he been getting away with this?

My wife is annoyed that I am so fascinated with this case.

That lady knows what’s up, they should have subpoenaed her.

I think they must have been told not to by higher-ups, because it would almost be neglectful NOT to after she recognized the dead dude.

The story given in the article is because she was married: but I think someone must have realized the dude was a spy, the girl was also involved in spying and just wanted to either cover it up or investigate it quietly.

Agreed that she was being evasive and acting almost as if she was being “kept” quiet or had a personal hand on the “murder/suicide” and didn’t want to revisit it. Either way they noted how obviously non-complient she was and i dont understand why that wasn’t enough evidence to investigate further.

Very strange.

The investigator apparently didn’t want to cause a family scandal, because the lady was married.

Yeah I read that but surely after his image was sent international and requesting help from abroad they could have atleast made her give up some info in secret. It seems like a waste of a possible lead. Hell, even her own daughter thinks she knew something so it couldn’t have been easy to let her go.

Has he ever denied being a part of this?

Well, he has never not denied it. He’s denied things in the past, I’m sure, but not this one. Not ever.

I think that’s all we need to know.

Adelaide has plenty of serial killers without the addition of Cruz, thanks

Pingback: In 1948, A Man Was Found Dead On A Beach In Adelaide And The… | JustaFact

60 minutes Australia story on the incident.

There’s a three part episode on this from the Astonishing Legends podcast that is pretty good. They get into a few of the different theory’s and do a decent job of connecting some of the stranger dots:

https://itunes.apple.com/ca/podcast/astonishing-legends/id923527373?mt=2&i=367182529

I am no code cracker by far and I don’t know if this is just a coincidence but I do love mysteries….I read the first line in the code as и Яго Авад (underlined) M цао I. I think that it translates to, and Iago Awad (underlined) 40 C.A.O. (Chief Administrative Officer) 10 OR Iago Awad (underlined) 40 T.S.A.O. (two-step acridine orange). I think that the book is just to confuse. I found the ‘w’ looked more like and ‘и’ and ‘L”I’ more of a ‘ц’. Did others try the code this way too? I don’t think the words are crossed out but a crappy attempt to underline the importance.

Edit: the next line if it holds to my thoughts could be: шт вим райет р or peice Wim Rayet 100. The ‘x’ in the line from that I think is a ‘ж’ meaning well underlined. Then, м цаво аиау с, or 40 with Tsavo Aiau. The last line is tricky but I think it is, о тт мтсамстгав, of comrades in Mt. Samstga. I think this is a list of names, Iago Awad, Wim Rayet, and Tsavo Aiau are people.

I wonder if the numbers have anything to do with the book now. My English translation would be, and Iago Awad 40 C.A.O. 10 peice Wim Rayet 100 well 40 with Tsavo Aiau of comrades in Mt. Samstga (Germany)

Edit: the whole thing I think says and Iago Awad hand C.A.O. flung peice Wim Rayet more wellhand with Tsavo Aiau of comrades in Mt. Samstga (Germany)

There is a very good Australian history podcast that talks at length about this. Please, don’t just listen to this episode. Their episodes on the wreck of the Batavia are up there with Dan Carlin for informative entertainment. They are well worth listening to, whether you are a citizen of Australia or a citizen of the world.

I have solved it! ‘Taman Shud’ written backwards is ‘duhS namaT’.

Don’t know what that means though.

Here is the thing about George Marshall, the man found dead with a Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám. He was found in Ashton Park, Sydney, near Clifton Gardens, which is where Jestyn gave another copy of the same book to Alf Boxall two months later. Jestyn was training to be a nurse nearby a the time.

Been fascinated by this case for years. First, my husband was born in Iran and immediately I knew what Tamun shud meant. when I first read about it. It’s usually said in a comic manner. Just as when a child asks for more cake you would answer “tamun shud” – ie. all done, finished.

Secondly, by very strange coincidence, my father was in the British Army during WWII and carried a copy of the Rubaiyat with him all through the war. It had a red leather cover and was well worn. I’ve no idea what edition it was. However, his mother lived in New Zealand, and her husband often travelled to Australia for business. Her husband and his father had served with ANZAC during WWI. What is the connection with the Rubaiyat and the British army? And why would this nurse be giving a copy of the book to more than one man?

As for the code, what if it the letters are equivalent to the corresponding letters in the Persian alphabet? This man was definitely a spy. And the mystery is solvable.

As a long-time collector of many different edition of “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam”, one thing has repeatedly irritated me about this case – the copy of the book that floated through this mystery was NOT rare at all. Whitcomb & Tombs – the New Zealand publisher of this edition, with an outlet in Melbourne – released a hardcover quarto version in the 1940s and then – as was the practise with this work – re-issued it in a smaller format across the ensuing years to meet the demand. With its “Carpe Diem” message, this book was an international bestseller from the late Victorian era into the 1950s, and still sells today. If you look around most second-hand bookshops in Australia, you can pick up a copy of the exact, same edition pictured here for about 12 bucks. I have several. Saying that this book was rare just adds a lot of unnecessary woo-woo to a case that’s already impenetrable enough. Let it be.

Nobody has seen a picture of the book ….. all we have is hearsay.