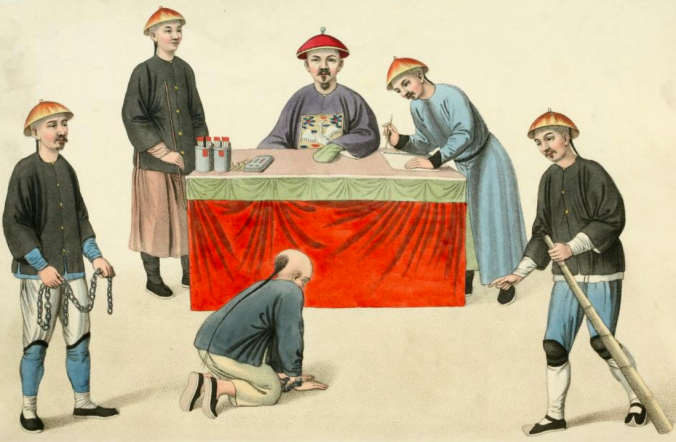

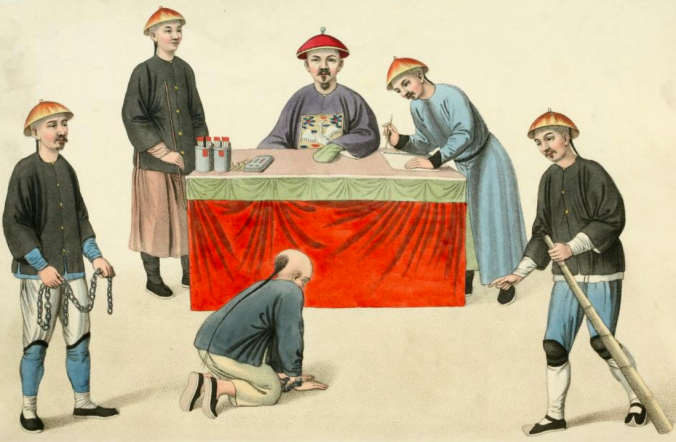

A Chinese prisoner – wearing the long pigtail, or queue, that was mandated for all indigenous subjects of the Celestial Empire – is interrogated by a Qing magistrate. Painting from Mason & Dadley’s voyeuristic classic The Punishments of China (1901).

China, in the middle of the eighteenth century, was the largest nation in the world – and also by a distance the most prosperous. Under the rule of a strong emperor, Hungli, and a well-established family (the Qing, or Manchu, dynasty), the Middle Kingdom was by then half-way through the longest period of calm in its long history. It had grown larger, richer and more cultured, its borders reaching roughly their modern extent. But it had also grown vastly more crowded; political stability, and the introduction of new crops from the Americas, led to a doubling of the population to around 300 million. At its peak, this growth was accelerating at an annual rate in excess of 13%.

This meant trouble, for it meant that wealth was far from evenly distributed. China remained a country of great contrasts: its ruling classes rich beyond the dreams of avarice, its peasants scraping a bare living from the soil. For those living at the bottom of the food chain – both metaphorically and literally – starvation was a constant possibility, one that grew ever more starkly real the further one travelled from the rich agricultural floodplains around the Yangtze River. By the late 1760s, many peasants were forced to turn to begging to survive, wandering miles from their homes to throw themselves upon the mercy of strangers. Tens of thousands of such forced migrations led inevitably to conflict. They also led to one of the strangest outbreaks of panic and rumour known to history.

China under the Manchus, showing the empire’s growth between 1644 and 1800. The soulstealing panic took place along the country’s eastern coast, between the Yangtze and Beijing. Click to view in larger resolution.

Among the hundreds of victims of this panic was an itinerant beggar by the name of Chang-ssu, who came from the province of Shantung. Chang-ssu travelled in company with his 11-year-old son, and between them the pair made an insecure living by singing a romantic folk song, ‘Lotus petals fall,’ to crowds of peasants whom they drummed up in their wanderings from village to village. By the end of July 1768, the two beggars had got as far as the gates of Hsu-chou, a city about 200 miles south of their home, when – at least according to Chang-ssu’s later confession – they were accosted by a tall man whom they did not know. The stranger asked them what they did for a living and, on hearing that they begged, he offered them employment – 500 cash for every peasant pigtail they could clip. (The cash was the imperial currency at the time; 500 cash was worth approximately half an ounce of silver.) The stranger refused to tell Chang-ssu and his son what he wanted the hair for, but he did offer them some help: a pair of scissors and a small packet of powder which, he explained, was a “stupefying drug.” Sprinkle the powder on the head of a victim and he would fall to the ground insensible. Then his pigtail – or queue – could easily be clipped.

The work sounded easy enough, and Chang-ssu accepted the commission – so he said. He and the stranger parted, making arrangements to meet up again later on the border with a neighbouring province, and father and son continued on their way, making for the city of Su-chou. In the course of their journey, at a village named Chao, they tried the stupefying powder on a local labourer. Gratifyingly, the man collapsed; Chang-ssu took out his scissors, snipped off the end of the man’s queue, and tucked scissors and the hair in his travelling pack. The beggars did not get far, however. Only a mile or two outside the village they were overtaken by a group of constables, arrested and hauled off to the county jail – suspected, they were told, of the vile crime of soulstealing. Continue reading →