Colonel Tom Parker—the title was awarded to him by Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis in 1948 for political services rendered—claimed until 1982 to have been born in West Virginia. In fact he was a Dutchman, and the circumstances under which he left the Netherlands in 1929 remain a puzzle to this day.

The Colonel always was a mystery. But that was very much the way he liked it.

It was, of course, a tough trick to pull off, because the Colonel’s name was Tom Parker, and Tom Parker managed Elvis Presley. Since Elvis was the biggest name in the entertainment industry, his manager could hardly help appearing in the spotlight, too. For the most part that was not a problem, because Parker had a showman’s instincts and he enjoyed publicity. But, even so, he was always anxious to ensure that attention never settled for very long on two vexed questions: exactly who he was and precisely where he came from.

So far as the wider world knew, the Colonel was Thomas Andrew Parker, born in Huntingdon, West Virginia, some time shortly after 1900. He had toured with carnivals, worked with elephants and managed a palm-reading booth before finding his feet in the early 1950s as a music promoter. Had anyone taken the trouble to inquire, however, they would have discovered that there was no record of the birth of any Thomas Parker in Huntingdon. They might also have discovered that Tom Parker had never held a U.S. passport—and that while he had served in the U.S. Army, he had done so as a private. Indeed, Parker’s brief military career had ended in ignominy. In 1932, he had gone absent without leave and served several months in military prison for desertion. He was released only after he had suffered what his biographer Alanna Nash terms a “psychotic breakdown.” Diagnosed as a psychopath, he was discharged from the Army. A few years later, when the draft was introduced during the World War II, Parker ate until he weighed more than 300 pounds in a successful bid to have himself declared unfit for further service.

For the most part, these details did not emerge until the 1980s, years after Presley’s death and well into the Colonel’s semi-retirement (he eventually died in 1997). But when they did they seemed to explain why, throughout his life, Parker had taken such enormous care to keep his past hidden—why he had settled a lawsuit with Elvis’ record company when it became clear that he would have to face cross-examination under oath, and why, far from resorting to the sort of tax-avoidance schemes that managers typically offered to their clients, he had always let the IRS calculate his taxes. The lack of a passport might even explain the single greatest mystery of Presley’s career: why the Colonel had turned down dozens of offers, totaling millions of dollars, to have his famous client tour the world. Elvis was just as famous in London, Berlin and Tokyo–yet in a career of almost 30 years, he played a total of only three concerts on foreign soil, in Canada in 1957. Although border-crossing formalities were minimal then, the Colonel did not accompany him.

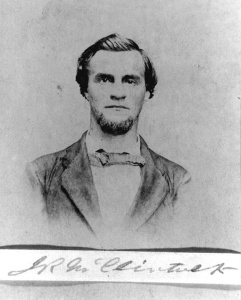

Parker serving in the U.S. Army, c.1929. Photographer unknown.

Although it took years for the story to leak out, the mystery of the Colonel’s origins had actually been solved as early as the spring of 1960, in the unlikely surrounds of a hairdressers’ salon in the Dutch town of Eindhoven. There a woman by the name of Nel Dankers van Kuijk flicked through a copy of Rosita, a Belgian women’s magazine. It carried a story about Presley’s recent discharge from the U.S. Army, illustrated by a photo of the singer standing in the doorway of a train and waving to his fans. The large figure of Elvis’s manager, standing grinning just behind his charge, made Dankers-van Kuijk jump.

The man had aged and grown grotesquely fat. But she still knew him as her long-lost brother.

Continue reading →