The Siberian taiga in the Abakan district. Six members of the Lykov family lived in this remote wilderness for more than 40 years–utterly isolated and more than 150 miles from the nearest human settlement.

Siberian summers do not last long. The snows linger into May, and the cold weather returns again during September, freezing the taiga into a still life awesome in its desolation: endless miles of straggly pine and birch forests scattered with sleeping bears and hungry wolves; steep-sided mountains; white-water rivers that pour in torrents through the valleys; a hundred thousand icy bogs.

Siberian summers do not last long. The snows linger into May, and the cold weather returns again during September, freezing the taiga into a still life awesome in its desolation: endless miles of straggly pine and birch forests scattered with sleeping bears and hungry wolves; steep-sided mountains; white-water rivers that pour in torrents through the valleys; a hundred thousand icy bogs.

This forest is the last and greatest of Earth’s wildernesses. It stretches from the furthest tip of Russia’s arctic regions as far south as Mongolia, and east from the Urals to the Pacific: five million square miles of nothingness, with a population, outside a handful of towns, that amounts to only a few thousand people. When the warm days do arrive, though, the taiga blooms, and for a few short months it can seem almost welcoming. It is then that man can see most clearly into this hidden world–not on land, for the forest can swallow whole armies of explorers, but from the air. Siberia is the source of most of Russia’s oil and mineral resources, and, over the years, even its most distant parts have been overflown by prospectors and surveyors on their way to backwoods camps where the work of extracting wealth is carried on.

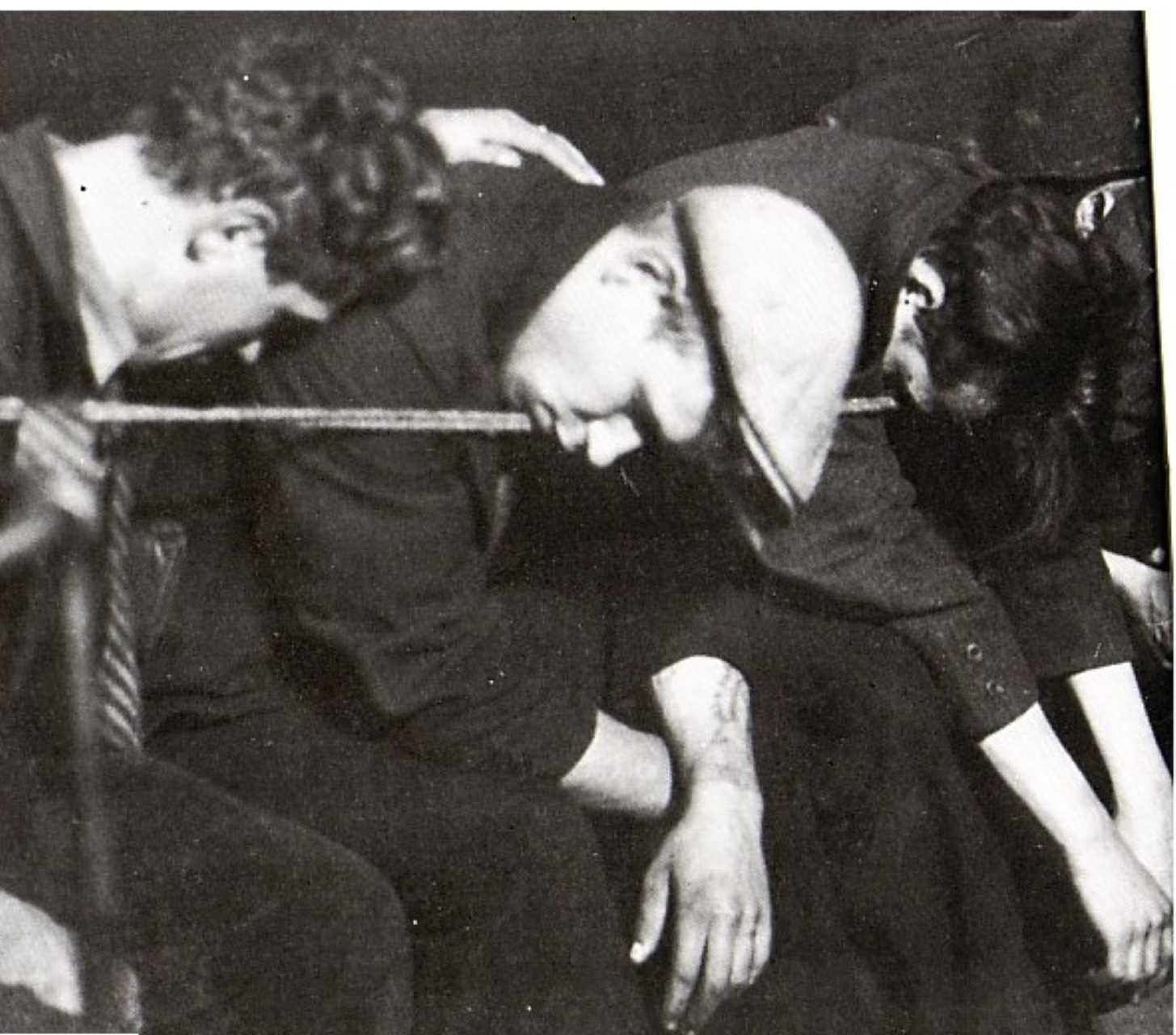

Karp Lykov and his daughter Agafia, wearing clothes donated by Soviet geologists not long after their family was rediscovered.

Thus it was in the remote south of the taiga in the summer of 1978. A helicopter sent to find a safe spot to land a party of geologists was skimming the treeline a hundred or so miles from the Mongolian border when it dropped into the thickly wooded valley of an unnamed tributary of the Abakan, a seething ribbon of water rushing through dangerous terrain. The valley walls were narrow, with sides that were close to vertical in places, and the trees swaying in the rotors’ downdraft were so thickly clustered that there was no chance of finding a spot to set the aircraft down. But, peering intently through his windscreen in search of a landing place, the pilot saw something that should not have been there.

It was a clearing, 6,000 feet up a mountainside, wedged between the pine and larch and scored with what looked like long, dark furrows. The baffled helicopter crew made several passes before reluctantly concluding that this was evidence of human habitation—a garden that, from the size and shape of the clearing, must have been there for a long time. It was an astounding discovery. The mountain was more than 150 miles from the nearest settlement, in a spot that had never been explored. The Soviet authorities had no records of anyone living in the district.

The Lykovs lived in this hand-built log cabin, lit by a single window “the size of a backpack pocket” and warmed by a smoky wood-fired stove.

The four scientists sent into the district to prospect for iron ore were told about the pilots’ sighting, and it perplexed and worried them. “It’s less dangerous,” the writer Vasily Peskov notes of this part of the taiga, “to run across a wild animal than a stranger,” and rather than wait at their own temporary base, 10 miles away, the scientists decided to investigate. Led by a geologist named Galina Pismenskaya, they “chose a fine day and put gifts in our packs for our prospective friends”—though, just to be sure, she recalled, “I did check the pistol that hung at my side.”

As the intruders scrambled up the mountain, heading for the spot pinpointed by their pilots, they began to come across signs of human activity: a rough path, a staff, a log laid across a stream, and finally a small shed filled with birch-bark containers of cut-up dried potatoes. Then, Pismenskaya said,

beside a stream there was a dwelling. Blackened by time and rain, the hut was piled up on all sides with taiga rubbish—bark, poles, planks. If it hadn’t been for a window the size of my backpack pocket, it would have been hard to believe that people lived there. But they did, no doubt about it…. Our arrival had been noticed, as we could see. The low door creaked, and the figure of a very old man emerged into the light of day, straight out of a fairy tale. Barefoot. Wearing a patched and repatched shirt made of sacking. He wore trousers of the same material, also in patches, and had an uncombed beard. His hair was disheveled. He looked frightened and was very attentive…. We had to say something, so I began: ‘Greetings, grandfather! We’ve come to visit!’ The old man did not reply immediately…. Finally, we heard a soft, uncertain voice: ‘Well, since you have traveled this far, you might as well come in.’

Continue reading →