Now expanded, revised and updated to April 2017

Richard Honeck (1879-1976), an American murderer, served what was, at the time, the longest prison sentence ever to end in a prisoner’s release. Jailed in November 1899 for the killing of a former school friend, Honeck was paroled from Menard Correctional Center in Chester, Illinois on 20 December 1963, having served 64 years and one month of his life sentence. In the decades between his conviction and the time his case came to public notice again in August 1963, he received only a single letter – a four-line note from his brother in June 1904 – and two visitors: a friend in 1904, and a newspaper reporter in 1963.

Honeck, a telegraph operator and the son of a wealthy dealer in farm equipment, was 21 years old when he was arrested in Chicago in September 1899 for the killing of Walter F. Koeller. He and another man, Herman Hundhausen, had gone to Koeller’s room armed with an eight-inch bowie knife, a sixteen-inch bowie knife, a silver-plated case knife, a .44 caliber revolver, a .38 caliber revolver, a .22 caliber revolver, a club, and two belts of cartridges. They also carried a getaway kit: two satchels filled with dime novels, obscene etchings, and clothes from which the names had been cut (New York Times, 4+5 September 1899).

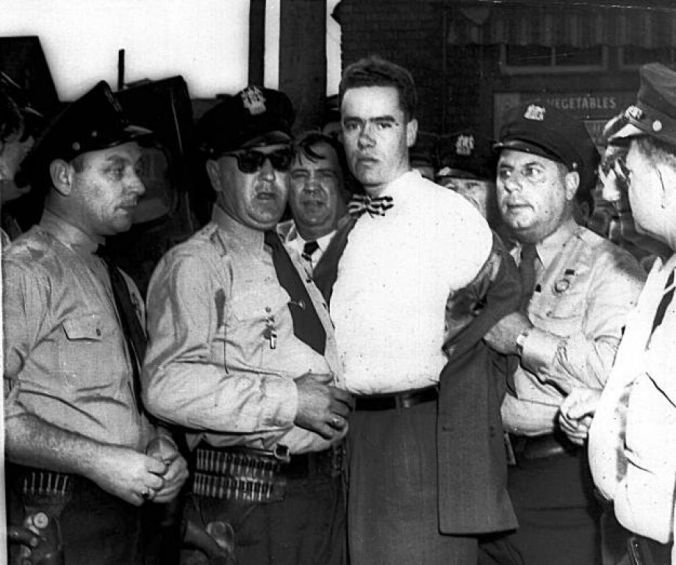

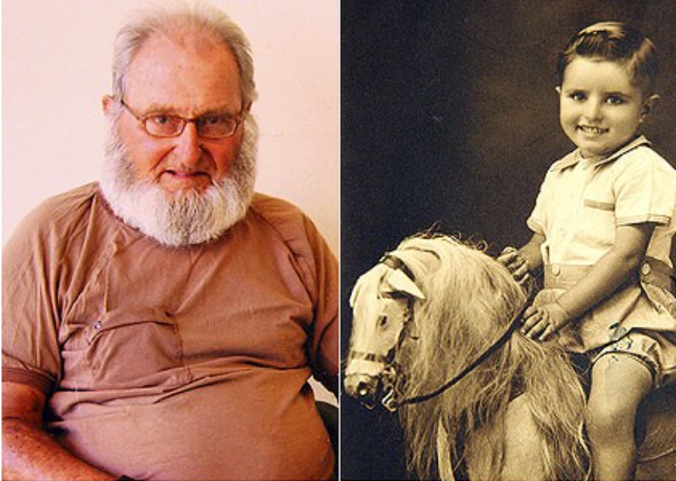

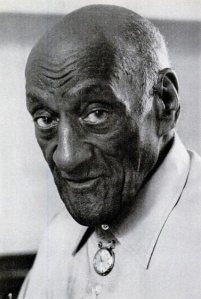

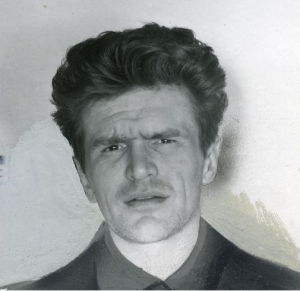

Richard Honeck before and after: mugshots taken at the time of his arrest (1899) and his parole (1964).

Koeller, who was later found by the police sitting in a chair stabbed in the back, had testified for the prosecution some years earlier when Honeck and Hundhausen were charged with setting a number of fires in their home town, Hermann, Missouri (New York Times, 5 September 1899). According to a confession made by Hundhausen, the two men had sworn revenge and had planned Koeller’s murder in considerable detail. Honeck, Hundhausen said, had stabbed the dead man with the eight inch bowie knife (Ibid and Chicago Tribune, 5 September, 22+25 October, 5 November 1899).

It was left to a latter-day Associated Press reporter, the memorably-named Bob Poos, to shine a spotlight on Honeck’s case in 1963 after seeing a reference to it in the Menard prison newspaper. Poos noted that after his initial article was published in the papers, the aged murderer received a mailbag of 2,000 letters, including a proposal of marriage from a woman in Germany, offers of employment, and gifts of money in sums ranging from $5 down to 25 cents. Honeck, who was permitted under prison rules to answer one letter per week, observed: “It’ll take a long time to deal with these.”

Clara Orth shows Honeck the scrapbook she had assembled filled with news stories about him, December 1963

Honeck spent the first years of his sentence in Joliet Prison, where in 1912 he stabbed the assistant warden with a hand-crafted knife. He served 28 days in solitary confinement for that infraction, but had a clean record after moving to Menard, where he worked for 35 years in the prison bakery. “I guess I’d have to be pretty careful if I got paroled,” the old lag concluded when interviewed by Poos. “There must be an awful lot of traffic now, and people, compared with what I remember.” (Chicago Tribune, 25 August and 27 October 1963.)

Poos got the chance to find out whether he was right when he accompanied the “sprightly” 84-year-old Honeck after his release as he was escorted to St Louis airport to catch a flight to San Francisco. “The old man,” he wrote, “was visibly amazed at the progress that had passed him by while he sat behind prison bars. During the car trip from Chester to St Louis, Honeck said, ‘Why, we must be going 35 miles an hour.’ The driver, Warden Ross Randolph, answered, ‘Actually, Richard, we’re going 65.’ Later, on the jet, Honeck remarked, ‘I travelled faster in that car today than I ever had in my life, and now we’re going almost 10 times that fast – and six miles up in the air, too.’”

Honeck was met at San Francisco airport by his niece, Mrs Clara Orth, who had been alerted to his extraordinary story by Poos’s original news report. She had quit her job to care for her uncle, selling her one-bedroom trailer home and buying another in Oregon which had two bedrooms for them (St Petersburg Evening Independent, 27 December 1963 + Tuscaloosa News, 1 January 1964).

Orth – who was Honeck’s sister’s daughter – had some family memories to recount as well. Her mother had died a couple of years after Honeck went to jail, and her widowed father sent her to Hermann to live with her grandfather, Honeck’s father, and an aunt. In six years in Missouri, Orth recalled, “Uncle Richard’s father and sister never once mentioned him.” Interviewed again at the time of Honeck’s death, Orth said that her uncle had slowly become senile and had to be placed in care. “He wasn’t bitter,” she added. “He decided long ago that if he had to be in prison that he would make the best of it. Since he got out he’s had a glorious time.”

Richard Honeck was the first prisoner to attract widespread media attention simply because of the length of time he’d served. He lived on for more than a decade after his release, dying at the age of 97 in an Oregon nursing home ( St Petersburg Times, 30 December 1976). But while his record-breaking stretch probably was unique in its day, the 64 years plus change he served has since been exceeded at least eight other cases…

Coming up:

[1] In depth: Charles Fossard (70 years, the current world record-holder) and “Old Bill” Wallace (63 years; died, still incarcerated, aged 107)

[2] In depth: The case of Paul Geidel (68 years)

[3] In depth: The case of Van Dyke Grigsby (66 years and a Johnny Cash song)

[4] In depth: The case of Frank Smith (67 years and the current longest-serving man)

[5] In depth: The case of Howard Christensen (64 years of being obnoxious)

[6] Longest spells in solitary confinement

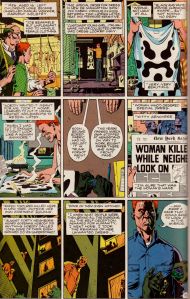

[7] State-by-state capsule studies of longest sentences served, featuring ‘Crazy Jimmie’ Williams, Leslie van Houten and the Manson Family, ‘Old Fitz’ Fitzgerald, the Lipstick Killer, the Starved Rock Murderer, Warren Nutter, the Boston Boy Fiend, bestiality in Missouri, death row poetry, the Kitty Genovese case, and a mid-sentence West Coast road trip for West Virginia’s leading badman…

[8] Longest sentences served outside the U.S., featuring the Kissing Point Mutilation Murder, bride purchasing in Denmark, the Man in the Iron Mask, and Ian Brady…

[9] Jouanna Thiec and the Huguenot connection

[10] Listing of all inmates with in excess of 60 years served

[11] Methodology, sources and comments

Richard Honeck was the subject of significant press interest at the time of his parole. Below is a gallery of press photos made available at the time of his release. Click on any image to view it in higher resolution.

Charles Fossard and the Australian connection

Sifting through the vast mass of material accumulated in the course of the research for this essay, it becomes clear that one factor, above any other, increases the chance that prisoners will serve out vastly lengthy sentences: the diagnosis of a mental illness. Being sent to a secure hospital, rather than a prison, means that a convict is likely to enjoy more comfortable conditions, or at least a considerably laxer regime, than he would do if he was in prison. But it also places him beyond the reach of the parole system, and there’s often a presumption that somebody deranged enough to have committed violent crimes might do the same again if they are ever released – irrespective of their doctors’ judgement. Certainly there are cases of prisoners who were eventually judged sane by those charged with caring for them who nonetheless remained behind bars, whether for political reasons or simply to guarantee public safety.

Restraints, much used in Fossard’s time, displayed inside J-Ward, the Australian state of Victoria’s secure mental facility in Melbourne. Photo by Darren Ward.

Combine mental illness with a major crime committed in a felon’s youth, then, and you have the recipe for an exceptionally long spell inside. That is certainly true of the inmate who seems to have completed the longest sentence ever served: Charles Fossard, a French immigrant to Australia who killed a man in Skye, just south of Melbourne, on 28 June 1903. Fossard (no doubt originally Foussard) was then just 21 years old; he was tracked down, interrogated, judged insane, and then incarcerated on 21 August that same year. Sent on to the grim secure hospital known as J-Ward, part of Melbourne’s Ararat Lunatic Asylum, he remained there until his death, aged 92, on 19 June 1974. All told, that meant that Fossard served out very nearly 71 years inside – and served them in a place that even the notoriously tough Australian criminal Mark “Chopper” Read observed was “a terrible place. There was a shit bucket in the middle of the room. People slept on the concrete floor. Meal times were like the feeding of animals. Some people couldn’t have their straightjackets removed, they were that mad. So people still wearing their straightjackets would just dunk their heads into the bowls of food.”

As for the crime that put him there: the “Skye Tragedy”, as contemporary Australian newspapers referred to the killing, was distressingly banal. Fossard, a former sailor who had jumped ship at Sydney three years earlier, was a vagrant down on his luck when he shot and killed an elderly man named William Ford after Ford turned him away from his home. He was caught two weeks later, still wearing his victim’s old boots.

The 1989 funeral of Bill Wallace, who died, still incarcerated, one month shy of his 108th birthday.

While youth and mental illness are a potent pairing, though, J-Ward records also contain a single example of a far rarer combination of circumstances: mental illness and extreme old age. Bill Wallace was 46 when he shot dead a man named Ernest Williams during an argument over a cigarette in a Melbourne cafe in 1926. In normal circumstances, his age alone would have been enough to deny Wallace a place on this listing. But old Bill was far from normal. He lived on, and on, dying only after serving more than 63 years inside. He was by then just one month shy of 108 – the oldest prisoner by far of whom I’ve found a record.

Further memories of J-Ward in Bill Wallace’s time are provided by the prison’s former pastor, Gordon Moyes, who visited during the 1960s, and they give some idea of the sort of conditions that the old prisoner experienced as he lived into his second century:

On my first day in Ararat I was given a massive iron key to open the thick, heavy, iron and wood doors to the maximum security division to enable me to visit cell to cell the psychotic prisoners… J Ward was built last century of heavy blocks of blue granite with high walls topped with rolls of barbed wire. Every gate and window was barred with steel bars one and a half inches thick.

The prisoners were considered the most dangerous in the country and the people in the community looked up to the top of the hill where the psychiatric prison stood like a great castle, fearful of the night when the sirens might go announcing a mass escape when they would all be murdered in their beds. There was no love for those prisoners in Ararat.

The prisoners I met as I went from cell to cell or stopped and talked to in the exercise yard were a strange mixture. They were the insane murderers of Victoria marked “Never to be released” or “To Be Held At The Governor’s Pleasure”. There was a man who constantly barked like a dog, and another man who would ask you frequently if you had ever sawn a man up into small pieces with a wood saw as he had.

Old Bill Wallace, the thick end of his way through spending 64 years in Australia’s most infamous insane asylum.

It’s worth asking why a man of 107 continued to live in such surroundings. The truth seems to be that Bill Wallace was the perfect exemplar of the long-serving mental patient. Had he been an ordinary prisoner, it seems probable, he would have secured parole well before his hundredth birthday – being judged unlikely to pose any sort of danger to his community. And as a heavily-monitored inmate of J-Ward, he was surely by that point unlikely to commit further crimes. But he was beyond the reach of normal prison systems, and had become institutionalised in the one place most likely to keep him alive, and equipped to keep him confined – an institution that, as “Chopper” Read observed, was not merely “a dank legend in the minds of men who have been in it,” but also “a bit like the Australian cricket team. It was harder to get out of than get into.”

The case of Paul Geidel

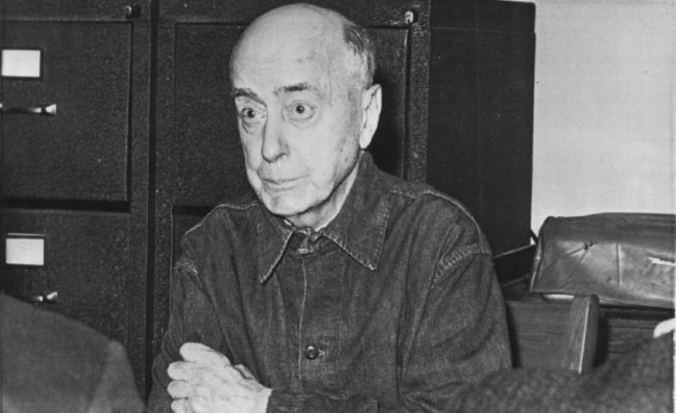

When Richard Honeck was released, Paul Geidel was already more than 50 years into his own sentence for a second-degree murder. He went on to surpass Honeck’s record, and eventually served 68 years, eight months and a day in various New York state hospitals and prisons.

Geidel had been only 17, and working as a bellhop at New York’s high-toned Iroquois Hotel, when he broke into the apartment of the rumoured-to-be-wealthy William Jackson, 73, and killed his victim by choking him with a chloroform-soaked rag. It was harder than he expected – “The old man put up a fight,” he said – and he got away with nothing but $7 in cash, a watch and a stickpin in exchange for Jackson’s life.

That was in September 1911, and Geidel was finally released on 7 May 1980, at the age of 86. His case differed from Honeck’s in two key respects. Firstly, he was initially sentenced not to life imprisonment but to twenty years to life, being later declared insane and moved to a hospital for the criminally insane. Secondly, Geidel was offered parole at an earlier date than was Honeck – in 1974, when he had served only 62 years. By then, he had become institutionalised and he declined release, voluntarily choosing to remain confined for an additional six years.

I take a special interest in his story because of a strange coincidence: Geidel’s crime took place in an apartment next door to the one owned by Charles Whitman, who was New York’s district attorney at the time. Whitman, it is reported, took a personal interest in the case and “extracted a confession or two.” This comes as no surprise to me, since Whitman was also the politically-motivated prosecutor responsible for the arrest and execution of Charles Becker, a corrupt New York cop found guilty of the murder of a gambler named Herman Rosenthal in two notorious trials of 1912 and 1914 largely as a result of Whitman’s determination to hound him to the electric chair. The Becker case and Whitman’s behaviour in it were the subject of my book Satan’s Circus.

The case of Van Dyke Grigsby

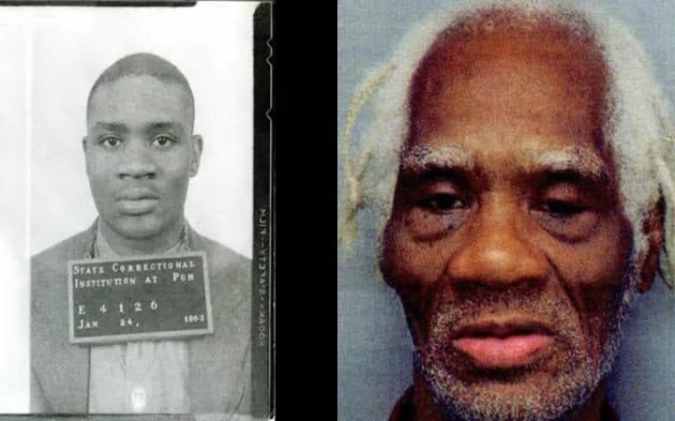

Paul Geidel’s U.S. record for time served was for many years most closely rivalled by the case of – the in many ways vastly more interesting – Johnson Van Dyke Grigsby (probably February 1886-18 May 1987), of Jefferson County, Kentucky. Grigsby was convicted of second degree murder in 1908 and eventually paroled from Indiana State Penitentiary in Michigan City in 1974, having served 66 years, four months and one day (24,229 days, allowing for leap years) of his life sentence. He had been 56 years into that stretch at the time that Honeck was paroled, and was 89 when he was freed. His sole possessions at that time were a well-thumbed Bible, three old watches, a bottle of foot spray, and a packet of tobacco.

Grigsby entered the pen as prisoner 4045 on 8 August 1908 – having travelled cross-country for several days in a horse and cart to get there – and was freed on 9 December 1974. He had been convicted of knifing a man named James Brown to death in a saloon in Anderson, IL, on 3 December 1907.

The fight broke out over a game of five card stud poker. As Grigsby remembered it, “I never should have been sentenced to [serve a term for] natural life because that murder was more suicide than murder… I was in this saloon, just mindin’ my business, and this fellow comes up to me. I always wore a big diamond in them days. And he seen that diamond. Come up and said, ‘Wanna play some cards?’

“I had an ace, king, jack and deuce in my hand when he stood up and came at me. I had this little deerfoot knife that I pulled out and just cut him on the shoulder. He was bleeding, but so drunk he wouldn’t see a doctor… Stayed at the bar like a crazy man or something ‘stead of gettin’ to a hospital. He was a fool, is what he was… Just kept saying, ‘I don’t need no help.’ We even got a doctor to his house, but he went to bed and didn’t want no doctor.”

The victim, who was white, was found lying dead on his blood-soaked mattress the next morning, Grigsby added, and the sheriff who arrested him told him: “You couldn’t have picked a better one there, Van Dyke. He was a mean S.O.B.” In this telling of the story, Grigsby owed his sentence mostly to the machinations of a prosecutor who was running for the senate and wanted to look tough on crime; as he saw it, he had the last laugh, because although the DA who convicted him won the election, he was “dead in a year.”

At other times, however, Grigsby – who was the son of freed slaves – said that things had gone down rather differently. Brown had had a knife, he told the Kokomo Tribune, and he had grabbed it from him during their fight; on another occasion, he admitted that after the row erupted over the card table, he left the saloon and visited a pawn shop to redeem a knife that he had pledged there – thus establishing the premeditation necessary to justify a life sentence.

Research suggests that elements of all these various accounts combine to form the truth. Genealogist Reginald Pitts, who looked into the story and read the original sources, tells it this way: “According to the transcript of the trial, Mr Brown and Van were playing poker and started fighting. Curses and racial slurs were uttered, and Mr Brown pulled a knife on Van. Van left the bar, went home and got his own knife. Mr. Brown saw Van coming up the street back to the bar. He picked up a chair and threw it at Van, who dodged it, and then lunged at Mr Brown with his knife and stabbed him to death. Supposedly, the lawyer told Van to plead guilty to second degree murder in order to escape the electric chair.”

Grigsby seems to have been a model prisoner in the mould of the post-Joliet Richard Honeck. His main pass-times were reading the Bible (two of his three brothers were country preachers), an encyclopaedia and a dictionary. “That encyclopedia is an amazing book,” he said. “I read the whole thing from A to Z.” His other interest was boxing, and he reminisced frequently about the Jack Johnson-Jim Jeffries heavyweight title bout of 1910, although that had taken place a couple of years after he was imprisoned.

Like Paul Geidel, Grigsby became institutionalised during his long confinement, and spent a large part of his sentence under psychiatric observation – one source says nearly 50 years of it, another puts the time at 55 years. He found it difficult to adjust to freedom once it had been granted to him and he was sent to live in Woodview nursing home in Michigan City, where he kept mostly to himself and was described by staff as “moody” and friendless. He returned voluntarily to prison in 1976 after 17 months on the outside – a move he told one reporter he regretted – after complaining that life in his home was boring and that he had expected to be found a job “like being a porter in a barber shop… I could have done that, but there was no job. It was like being useless.”

Johnny Cash’s handwritten lyrics for the song Michigan City Howdy-Do sold at auction in December 2010, fetching $1,280. Click to view in higher resolution.

The old-timer was put up in the prison hospital because guards felt that, at 90 years old, he would struggle in the hurly-burly of the chow line, and he served a further several months there. His parole officer, John Rascka, said that Grigsby was a loner who preferred incarceration in the maximum security facility because it was all he knew and he was treated well. Most sources agree that he retained considerable vitality well into his 90s, maintaining physical fitness by dancing a “stiff-legged dance” of his own invention.

Grigsby remained “alert and reality-oriented”, the Bryan Times reported; added Jet: “He receives more attention than most inmates. The staff like him. He tells fabulous stories and they get a kick out of it.” Said one: “Van Dyke is just the sweetest old man, but he will use the ‘French language’ now and then.” And late in November of ’76, Grigsby left prison again, by now aged 91 and this time apparently for good. “I’ve been here too long. I’ll not be back,” he said as he was taken to the Marion County Home in Indianapolis. “I feel like I’ve been born again.”

Speaking in 1976, the old-timer said he had made 33 unsuccessful attempts to gain parole before finally being released. He added that he thought his sentence was cruel and sometimes wished the judge had sentenced him to hang, but added: “I’ve put all my trust in God. There’s got to be a meaning for this.”

Jet Magazine published this photo of the 92-year-old old lag’s socks, adding: “Grigsby has not forgotten everything. Anyone who looks at his socks might have been a little bit surprised to see that warm three-letter word embroidered there.”

Grigsby’s celebrity was such that Johnny Cash wrote a song about him entitled Michigan City Howdy Do and presented him with a colour television. Van Dyke’s last take on the justice system he was so intimately familiar with was: “Nobody likes it in prison. They make it as good as possible. Prison life is not really that bad. But nobody really wants to be here.” And his view of human nature was that little had changed in the course of his long stretch: “The people are the same. Just gettin’ you in trouble and all kinds of foolishness. Always gettin’ you in trouble. I keep to myself and don’t pay ’em no attention. Read my Bible. Why, that’s exactly what I do.”

The old man’s one other hobby, during his time in prison, was collecting keys – a habit that he kept up in his nursing home, and which Ebony journalist Hamilton J. Bims suspected was significant: “The keys may be signs of his lingering conviction that he is still a kind of prisoner.” Ebony, Dec 1975; St Petersburg [FL] Evening Independent, 9 Sep 1976; Jet, 16 Sep 1975 + 6 Jan 1977; Bryan Times, 9 Aug 1976; Beaver County Times [PA], 25 Nov 1976; Kokomo Tribune, 28 Nov 1979.]

The case of Frank Smith

No man featured on this listing came closer to a vastly earlier death than did Francis Clifford (Frank) Smith, the Connecticut burglar who is currently the world’s longest-serving prisoner.

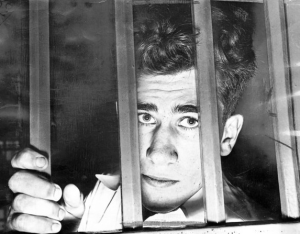

Smith has been incarcerated ever since 7 June 1950 for his involvement in the murder of a nightwatchman by the name of Grover Hart in Greenwich almost a year earlier. The 68-year-old Hart, who had been in his job for just three days, had been assigned to guard the premises of the upscale Indian Harbor Yacht Club and was killed on 23 July 1949 in the course of a break-in. The circumstances of the shooting remain murky; no agreed account of the manner in which Hart met his end has ever been decided on, and Smith himself was variously described by one contemporary source as “baby-faced,” and by another as “a scar-faced ex-convict.” In truth, however – and regardless of scars or time served – he was a mere 24 years old at the time of the killing, and a very small-time crook whose most recent heist had involved the theft of a box of cigars from a nightclub. He was also just one member of a three-man crew participating in the burglary, and, at least according to Leo J. Carroll (then the state trooper responsible for Smith’s arrest, but later Connecticut’s state liquor commissioner), probably not the man who actually fired three .22 bullets into the unlucky watchman.

Anyway, Smith’s co-defendant, a crook named George Lowden, copped a plea and escaped with a sentence for second degree murder; Smith himself was sentenced to death, and in June 1954 – three appeals, five reprieves and two stays of execution later – came within two hours of meeting his end in the electric chair. Death was so close, in fact, that he had had his hair shaved in preparation for the electrodes before his attorneys successfully wangled a last-gasp commutation on the basis of a fresh confession they had extracted from the third member of the burglary squad, one David Blumetti, who was by that time rotting in the infamous confines of Alabama’s hellish Kilby Prison. One wonders whether, 63 years and more than 69,000 prison meals further down the line, Smith has ever wished that things had played out differently that day.

Not for a while, quite certainly. By 1967, the sandy-haired lifer had done enough to earn himself a transfer to a minimum security prison farm at Enfield; there, entrusted with the keys to a work truck on 18 May, he made a break for freedom. Smith was on the lam for 11 days before the police tracked him down to Winthrop, Massachusetts, and recaptured him at gunpoint as he attempted to flee from the rear of what he’d hoped would be a safe house.

That miniature drama was the last time that Frank Smith troubled the media, though; in the 50 years since his return to jail, he’s served on and on and on without apparently leaving any trace of his progress in the shape of parole hearings or appeals for a release on compassionate grounds. He is now 92 years old, in his 67th year inside, and the senior man, by time served, in the entire US prison system.

Supreme Court of Connecticut appeals in the case of State of Connecticut v. Francis C. Smith, argued 12 June 1951 and 2 March 1954; Sunday Herald (Bridgeport [CT]), 16 December 1951 + 16 August 1953; Herald Magazine (Bridgeport [CT]), 23 September 1956; The Day (New London, C), 29 May 1967; Timothy Dumas, Greentown: Murder and Mystery in Greenwich, America’s Wealthiest Community.

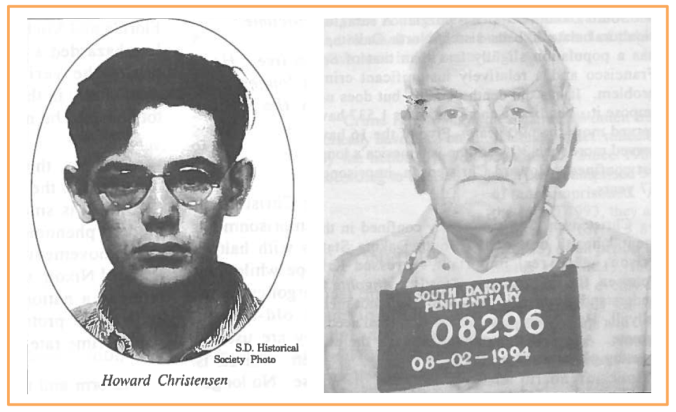

The case of Howard Christensen

Howard Christensen was sentenced to life in jail for murder and robbery in 1937, and paroled six-and-a-half-decades later. His would have been the very definition of a wasted life, if it wasn’t for the fact that his one significant action ended that of someone with far more to offer.

Christensen and an accomplice had admitted robbing and shooting a 26-year-old schoolteacher named Ada Carey in Onida, South Dakota, to steal $10 and her car. Christensen was 16 at the time; his accomplice, Norman Westberg, was 17. The two had hitched a lift with Carey and beat and shot their victim when she resisted their attempts to rob her. They were identified by Carey shortly before she died. The killers, who came from Chicago and had consciously determined to embark upon a life of crime, were captured by a sheriff’s posse as they hid in weeds near Onida and had to be taken to jail some way off in Pierre because the sheriff feared they would be lynched. [Joplin Globe, 22 May 1937] South Dakota did not have the death penalty in 1937, and at trial, the jury considered the pair’s claims that the gun had been discharged accidentally – but the boys were still sentenced to life in prison.

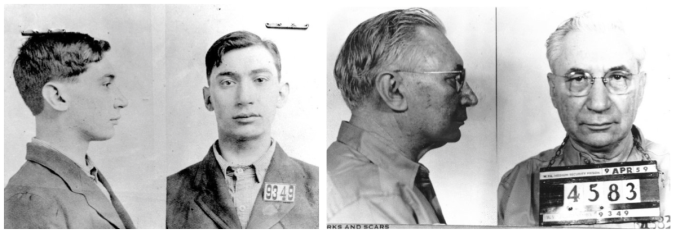

Howard Christensen before and after: at the time of his capture in 1937, and 57 years into his 64-year stretch. “I had life for murder, and they cut it to 200 years…”

Further details of the Christensen case can be found in E.L. Thompson’s book 75 Years of Sully County History, 1883-1958, which notes:

“The murder of Miss Ada Carey, of Blunt, on May 21, 1937, which was one of the worst crimes ever committed in South Dakota, brought a sudden end to a planned crime career of two Chicago youths, Howard Christensen, 16, and Norman Westberg, 17, whom Miss Carey had picked up as hitchhikers, but who later beat her up and shot her in an attempted hold-up on the highway several miles north of Onida. Miss Carey, who had been teaching school in the town of Frankfort for two years, had stopped in Gettysburg to visit a friend en route to her home in Blunt.

“The crime terminated with the wrecking of the car near the Myers farm about four miles north of Onida. According to officials, it was thought the shooting occurred in the vicinity of the hill south of Agar, coming down to Okobojo Creek. It was about here that Miss Carey was hit over the head with a hammer by Westberg, then shot by Christensen and fell out of the car as it came to a stop in the ditch. Putting her in the rear seat the boys then speeded on until they noticed a car following them, attempted to stop for a side-road and tipped over into the ditch. The boys abandoned the car and fled westward, while Frank Hiatt of Huron, who had been following them stopped at the scene of the accident briefly and then went on for help. He stopped at the William Ruckle farm where he requested Mrs. Ruckle to return and watch over Miss Carey, and then continued to Onida where he notified officials. Dr. V. W. Embree accompanied Sheriff Jack Reedy to the scene and brought Miss Carey to the hospital in Onida for immediate treatment. Although in a very weak condition, she was able to furnish a description of the boys and sign the statement taken by Attorney F. M. Ryan. She identified Westberg as the boy who shot her and Christensen as the one who hit her over the head with a hammer [sic – which of course leaves it quite moot as to which boy did what]. Miss Carey died at 2:50 that afternoon.

“Men from Onida, Agar, Gettysburg and surrounding territory searched the countryside and finally located the boys northwest of Onida on the Cottrill place hiding in a ditch among some weeds. They were brought to the courthouse for a brief questioning, then to the hospital where Miss Carey identified them, then back to the courthouse for further questioning. Sheriff Reedy then took them to Pierre when word of Miss Carey’s death was announced and threats were heard among the large crowd against the lives of the prisoners.

“The two boys pleaded “not guilty” to the crime. The jury’s verdict stated the boys ‘while engaged in the commission of a felony, killed and murdered Miss Carey.’ A life sentence is mandatory for murder in this state.

“At the time of the conviction a petition was signed by about 3,000 people in this area and filed with the Board of Pardons that these boys could never be pardoned.”

The case aroused such passions that it led directly to the reinstatement of capital punishment in the state, according to articles published in the 1990s.

Westberg hanged himself in 1943, but Christensen was still in prison in 1996, when his case was referenced by Paula Mergenhagen and Rachel Dickinson, in “The prison population bomb”, American Demographics Feb 1996. Mergenhagen and Dickinson noted: “South Dakota State Penitentiary officials wanted to put Christensen in a conventional nursing home, but they were afraid he wouldn’t be welcomed.”

Interior of the abandoned insane asylum at Yankton, SD, where Howard Christensen spent more than 30 years.

A very similar state of affairs was reported by the Burlington Hawk Eye of 21 August 1996, which described Christensen as “slightly demented” and said he had spent 58 years in jail and psychiatric hospitals – including more than 30, off and on, at the Yankton state mental facility. Unlike the inoffensive Richard Honeck, Christensen had “a long history of being obnoxious to his visitors and fellow inmates,” according to a prison spokesman at South Dakota State Penitentiary, where the murderer had received nine courses of electric shock treatment, and where was kept on the psychiatric ward. Officials were doubtful any nursing home would agree to take a tricky, notorious and unrepentent killer, who “harrassed visitors, refused to change his clothes, and was so unpleasant officials feared other inmates would attack him.”

Christensen’s personal hygiene, psychiatric unit manager Kris Petersen observed, “leaves something to be desired, but we work on that. We make sure he gets showered and shaved, that he’s eating properly, and receiving his medications.” For the most part, he was fortunate to spend so much time in a medical facility; his time in “general population” saw him suffer considerably from the attentions of other prisoners, and develop “a terrible habit of yelling and screaming all night long,” Petersen said, “which only intensifies this kind of negative behavioural cycle.” Consideration was given to subjecting Christensen to a frontal lobotomy to “render him more docile,” but that procedure was never carried out.

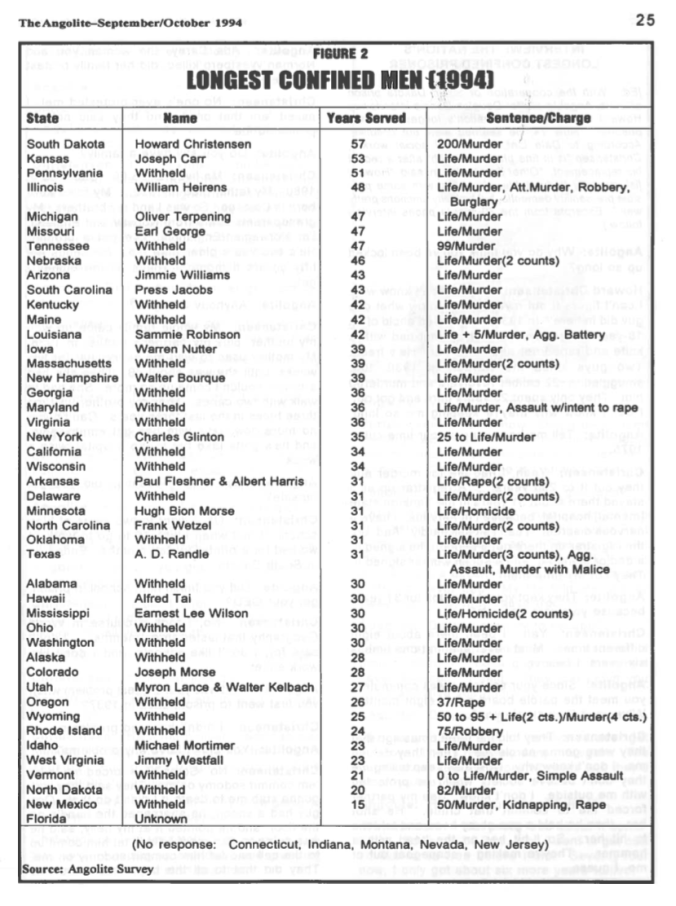

Thanks to the prisoners who staffed The Angolite – an award-winning journal written, edited and published by the inmates of the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, LA – we possess an unusual window into the experiences of a man serving out an extraordinary prison sentence. Christensen was interviewed by phone about his time in gaol in 1994, nearly 60 years into his sentence, when he was already 74.

Angolite: Why do you think you’ve been locked up so long?

Christensen: Why? I don’t know why. I can’t figure it out myself. You know what one guy did in here? In 1938, he grabbed ahold of an 18-year-old girl, and cut her up real bad with a knife and raped and killed her. He’s freed. Two guys killed the warden in 1938, too. Smuggled in .22 caliber revolvers and murdered him. They only spent 25 years here and got out. I don’t know why they’re keeping me here so long.

Angolite: You didn’t have any problems?

Christensen: No. Some guys forced me to let ’em commit sodomy on me. They said they was gonna stab me to death if I didn’t do that. One guy had a spoon, he’d sharpened the handle on the floor, and he pointed it at my belly, said he was going to stab me if I didn’t let him come up to my cell and let him commit sodomy on me. They did that to all the boys that come into the prison then. Old-timers. Mostly old men and that…. They called the guys like that ‘queens’. They called us all queens then.

Angolite: When these people were sodomizing you, what did you do about it?

Christensen: Nothing. I didn’t do nothing about it… I was afraid if I told the authorities, someone would murder me. They don’t like stool pigeons in here you know.

Angolite: How did you get them to leave you alone, eventually?

Chistensen: I don’t know. I just stopped doing that. I didn’t say anything. I didn’t like it, though, to tell you the truth.

Angolite: Have you ever had a girlfriend?

Christensen: No. Yeah, I had a girlfriend up at Yankton. She died in Bridgewater Rest Home about four years ago. She wouldn’t let me make love to her, though. She said, ‘I don’t do that. I’m a decent woman.’ She’s the only girlfriend I ever had. My ma told me to stay away from girls, they cause trouble.

Christensen’s sentence of life without the possibility of parole was reviewed midway through the 1970s and cut to one of 200 years – a seeming technicality that in practice made him eligible for parole. He spent some time in two half-way houses, but was returned to prison after “acting peculiar” and displaying bad table manners, according to state records. “He’s very easy to talk with,” said Pat Haley, chairman of South Dakota’s Corrections Commission. “He’s like a child in a lot of ways… his development was arrested about the time he went to prison.” His case manager, Bonnie Larson, confirmed this in 1994. “As a trusty [he] went on furloughs. Somebody here in [Sioux Falls] would pick him up. He’d go downtown for ice cream, and want to come back home. His socialization skills are at what I would term a pre-teen level… He’s funny, and he can play a lot of good cards. But as far as adapting to life, taking on responsibility, earning his own way…”

Christensen was finally paroled by Governor Bill Janklow some time in June 2001 on the grounds of health and was dead by June 2003. [Sioux Falls Argus Leader, 29 June 2003] That would suggest he served a sentence of 63 or 64 years. In fact we can narrow it down further, because the date of sentencing is given by the Portsmouth Times [Ohio], 5 June 1937, as that day’s date. Hence it seems that the longest Christensen could have served was 64 years and some days, and he must have fallen just short of Richard Honeck’s record.

Longest spells in solitary confinement

Albert Woodfox (left) and Herman Wallace (right) with their 11 year old British visitor, Poppy Richards.

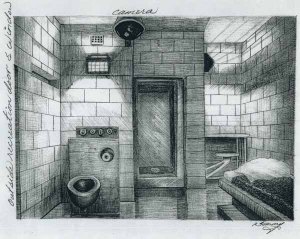

When Thomas Silverstein killed two fellow inmates and a prison guard at the federal gaol at Marion, Illinois, the authorities responded by issuing a “no human contact” extreme solitary confinement order, under which he spent 10,220 days (almost 28 years) as “America’s most isolated man,” the first part of it locked in a cell measuring 6×7 feet – so small he could touch both sides with his outstretched arms – for all but one hour a week. For his first 12 months of isolation, he was further punished by being refused all access to visitors, music, TV and reading materials, other than a Bible.

Wrote Silverstein (no choirboy – he was an armed robber and active member of the Aryan Brotherhood who had killed one other prisoner before he fetched up in Marion): “Due to the unchanging bright artificial lights and not having a wristwatch or clock, I couldn’t tell if it was day or night. Frequently, I would fall asleep and when I woke up I would not know if I had slept for five minutes or five hours, and would have no idea of what day or time of day it was.

Silverstein taught himself to draw during his lengthy stretch of solitary. This is his own sketch of his cell in America’s “supermax” AMX jail in Atlanta.

“I tried to measure the passing of days by counting food trays. Without being able to keep track of time, though, sometimes I thought the officers had left me and were never coming back. I thought they were gone for days, and I was going to starve. It’s likely they were only gone for a few hours, but I had no way to know.

“I was so disoriented in Atlanta that I felt like I was in an episode of the twilight zone. I now know that I was housed there for about four years, but I would have believed it was a decade if that is what I was told. It seemed eternal and endless and immeasurable.

“There was no air conditioning or heating in the cells. During the summer, the heat was unbearable. I would pour water on the ground and lay naked on the floor in an attempt to cool myself.”

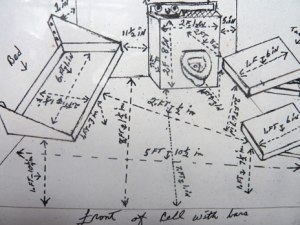

Equally worthy of note is the case of two imprisoned Black Panthers, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox, who when their case was reported by the BBC in 2012 had spent 40 years in solitary confinement for the murder of a prison guard named Brent Miller in 1972. Both men – originally jailed for armed robbery – say that they joined the Panthers in an attempt to improve the appalling conditions in Louisiana State Penitentiary; aside from a brief spell in 2008 spent in a high security dormitory, they spent 23 hours a day locked up alone for the whole of that time. They continued to protest their innocence.

Herman Wallace’s sketch of his solitary confinement cell. The obsessive interest evident in its exact dimensions may be a product of 40 years spent within its four walls.

A federal court ordered that Herman Wallace be released from prison on 1 October 2013 after his 1974 murder conviction was finally reversed. He was suffering from liver cancer and died three days later.

Wallace told his lawyer George Kendall that solitary confinement – in a cell that, in his case, was six feet by nine feet (three metres by two) – “is the cruellest thing one man can do to another.” He had kept in shape using dumb-bells made of old newspapers which he had constructed himself. The evidence for the two Black Panthers’ involvement in Miller’s death, most sources report, was weak; there were no fingerprints at the scene, and Miller’s wife stated she had doubts about the conviction and hoped the pair would be fairly treated. The case was prosecuted twice, and in both cases, convictions were overturned on appeal.

As for Woodfox, he was not released until early 2016, by which time he had completed 43 years and 10 months of almost continuous solitary confinement – during which he suffered numerous panic attacks and significant claustrophobia. He was then still in reasonable health, and told The Guardian (20 February 2016) that he and his friend had “made a conscious decision that we would never become institutionalised… We made sure we always remained concerned about what was going on in society – that way we knew that we would never give up. I promised myself that I would not let them break me, not let them drive me insane.”

The two men’s motto, Wallace said, was “always far apart, but never not together.” Some slight insight into their experiences in solitary is offered by a post written by a young British girl, Poppy Richards, who visited the pair around 2008. She had been writing to them for a year at the urging of her mother, self-professed “renegade potter” Carrie Reichardt.

“I think that there is something significant about the innocence of a child,” Richards wrote. “Being only 11 at the time, when I stepped into the visiting room of Louisiana State Penitentiary and ran up to Herman Wallace to give him a hug I was completely unaware of how strange this must have been to everyone else in the room. It was only a long time afterward that I realised. A white, 11 year old girl running into the arms of a convicted murderer, a peculiar sight to the other inmates, their families and prison guards alike.

“I asked Herman and Albert questions about their daily life, what was the food like? How long did they spend in their cells each day? I tried to imagine being contained 23 hours a day, constricted to a limited few occasional activities, and being served just about edible food onto the cell floor. Of course it was impossible, it was completely unimaginable to me, just as it is to most people.”

Albert Woodfox was released after legal manoeuvres that saw his murder conviction quashed and a plea of no contest entered to lesser charges of manslaughter and burglary.

General studies of the effects of solitary confinement make grim reading. Anything longer than around three months of such treatment, notes Terry Kupers, a professor of psychiatry at Berkeley, tends to result in heightened states of anxiety, including panic attacks, paranoia and disordered thinking. Compulsive actions increase, basic cognitive functions are dulled. Former Harvard Medical School faculty member Stuart Grassian adds that the worst aspect of such regimes is the lack of stimulation. Without it, he observes, “people’s brains will move toward stupor and delirium – and often people won’t recover from it.”

Listing of record U.S. sentences served, by state

With only a couple of exceptions, every American state has incarcerated felons for periods in excess of 40 years. Many of these cases are those of prisoners who had death sentences commuted. As one would expect, many also involve crimes committed against women and children, but there is also a second category, noticeably common, involving crimes committed (or said to have been committed) by blacks against whites.

Since life expectancies have improved substantially over the course of the last century, and prison conditions are on the whole better than they once were, too; and since there are presently around 160,000 prisoners serving life sentences in the US; and since almost one in three of those lifers are serving sentences that exclude the possibility of parole, it seems inevitable that all these records will eventually be beaten. Indeed, if Frank Smith of Connecticut – who began his sentence of life without parole for murder on 7 June 1950 – survives, Paul Geidel’s unwelcome milestone could be passed as early as 8 February 2019, and Charles Fossard’s on 7 March 2021.

Here, then, is a series of mini-studies of the longest sentences served in various places:

-

Today’s St Clair Correctional Facility, home to Roosevelt Youngblood in 2002, offers comforts that are a vast improvement on those typical in the Alabama prison system in the 60s…

Alabama. According to a newspaper article published in 2002, Alabama’s longest serving prisoner at that time was Roosevelt Youngblood, 61, who had been sent to prison – for life – for robbery in 1961, who had killed a total of three fellow inmates in the course of the 1960s and 1970s, and who was not due for parole until 2008. As Youngblood told it, responsibility for the murders he committed rested as much with the appalling Alabama prison regime as with him – he had killed simply to survive in a brutal, filthy and overcrowded penitentiary, run by a system so bad that it had to be taken over by the federal courts simply in order to ensure that inmates had access to things such as toothbrushes and flushing toilets. Being in prison in Alabama, he asserted was like “being out in the jungle with a bunch of cobra snakes.” Youngblood was not alone in this assessment: Alabama lawyer Alvin J. Bronstein describes Fountain, the facility he was held in as a place “shocking to to conscience,” where an average of 50 sexual assaults occurred each week, where “people were being raped, beaten, there was stealing and the guards were afraid to go in there and didn’t go in there.” If Youngblood was at Fountain in the 60s, Bronstein adds, “he would almost have [had] to [kill] to stay alive.” The Youngblood of 2002, however, was old for 61 – partially paralysed by a stroke, afflicted by cirrhosis of the liver (which sounds like a further indictment of the Alabama prison system) and suffering constant pain from a bullet lodged in his spine – an injury inflicted when he was shot by a guard for fighting with another inmate “who drew an ice pick on him.” He insisted on calling the other prisoners with whom he shared his time “associates”, not “friends” – which is perhaps not surprising when one considers that St Clair, the correctional facility where he was by then imprisoned, has been described by vice.com as one of the most dangerous lock-ups in the US, with five prisoner-on-prisoner killings in only 30 months, and “a toxic mix” of problems, which apparently included “overcrowding, a warden who doesn’t care what prisoners do to one another, and drug-dealing guards who sometimes order hits on inmates.” Youngblood slipped out of sight after featuring in that one report – published in the Tuscaloosa News, 12 May 2002 – but some legal documents supplied by a commenter [below] show that he died, apparently of cirrhosis of the liver, sometime in the first quarter of 2004. That means he must have served a total of around 44 years.

- Arizona. Betty Smithey [above] was the longest-serving female prisoner in the US at the time of her 2012 parole. She had completed 49 years of a sentence for the murder of a 15-month-old girl whom she had been babysitting.

Inmates at the Arizona State Prison Complex, in the desert at Florence – home to Jimmie Williams for almost 50 years.

- Arizona. “Crazy Jimmie” Williams probably wasn’t mad when he entered the Arizona State Prison complex at Florence in 1948, aged 17, after murdering his aunt. But the 49 years he spent inside its walls cannot have helped. Some days, recalled Michael Berger of the State Department of Corrections, he seemed quite lucid, but on others “he had long, drawn-out conversations with the clothes he was going to put on after a shower.” Like several of the prisoners I’ve investigated, Williams stayed in prison longer than he might otherwise have done because he had no close family and preferred not to apply for parole. He died, aged 66, of the effects of a stroke, still in jail. (Tuscon Citizen, 17 June 1999).

- Arizona’s Louis Taylor served the longest sentence – 42 years – that I have record of for prisoners who had their sentence vacated or overturned. He had been found guilty of setting a fire in a Tuscon hotel that killed 29 people. Evidence suggested that, while he was at the scene, he had actually been helping guests to escape the flames. Although not formally cleared, he had always pleaded his innocence and was eventually released as part of a deal that saw him plead ‘no contest’ to avoid the delay and cost of a retrial.

- California. Booker T. Hillery, who remains in prison coming up for 55 years after his conviction for murder, is serving time for the killing of a 15 year old girl, Marlene Miller, in 1962 and is California’s longest-serving male prisoner. Details of the case are contested. Hillery (who is black, while Miller was white) was convicted by an all-white jury and made extensive efforts between 1962 and 1985 to seek a retrial. Those who oppose his release point out that he was on parole for an earlier rape conviction at the time of the murder, and that at least one fellow inmate claims to have heard him confess to stabbing Miller.

-

Patricia Krenwinkel, centre, seen at the time of her trial. She is flanked by fellow Manson family members Susan Atkins (died in jail 2009) and Leslie Van Houten.

Meanwhile, Betty Smithey’s release [above] leaves Manson Family members Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten as almost certainly the longest-serving women in the US prison system. The pair were convicted on 25 January 1971 and – after commutation of their death sentences to life terms – had, as of April 2017, both served 47 years in the California penal system for their parts in the Family’s murders. (Van Houten spent six months out of prison, on bail awaiting a retrial, in 1978. Denied parole, for a 21st time, after her most recent hearing in June 2016 when Governor Jerry Brown personally intervened to overturn a recommendation that she be released, she remains in prison pending a further hearing scheduled for September 2017. She is now 67 years old.)

The case of “Old Fitz” Fitzgerald, paroled from Folsom in 1971, shows that long prison sentences were served out before the modern prison era. Richard Honeck’s near-contemporary put in a total of 59 years in jail for three separate offences, including the murders of a Montana sheriff and a San Gabriel policeman.

- Also worthy of mention is one old-timer, Charles “Old Fitz” Fitzgerald, a long-serving career criminal who was finally paroled from California’s Folsom Prison in 1971, at the age of 85. Fitzgerald was then the longest-serving inmate in the state, having first gone to the pen in 1908, aged 22. He served three years for burglary, and, after his release, killed a Montana deputy. That crime earned him a 100-year sentence, but he was paroled as a reformed character after only 11 of those years – only to kill again in 1926 while participating in a rum-running operation during Prohibition. “Old Fitz” served 45 years for that final crime, and survived his second parole by five years, dying aged 90 on 30 October 1976.

-

Murderous janitor Joseph Morse at the Boulder [CO] courthouse.

Colorado. Colorado University janitor Joseph Dyre Morse, the state’s longest-serving prisoner, was convicted in December 1966 of the rape and murder of CU coed Elaura Jacquette. She had been horribly assaulted in the organ practice room at the university’s Macky Auditorium – producing what Boulder police chief Dave Voorhis described as the most horrific crime scene he had ever investigated. Morse, who was turned in by members of his own family after arriving home with blood-soaked clothes, received an 888-year term and denied his guilt for years before eventually confessing in 1980. He died, still in prison, in 2005, 38 years into his sentence.

- Connecticut. Burglar Frank Smith remains in gaol 67 years on for the July 1949 murder of a nightwatchman during a break-in at a yacht club in Greenwich; see above.

-

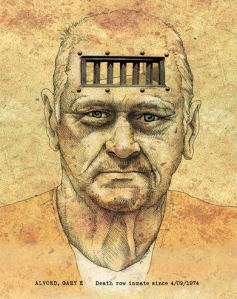

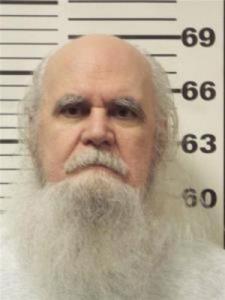

Florida. It seems that Gary Alvord – awarded the unwelcome soubriquet of “the man too crazy to be executed” by the Tampa Bay Times – holds the record for longest time spent on death row in the United States. He served 39 years for the 1973 killing of three women, seeing out eight presidents, nine Florida governors and two different death warrants before falling victim to a brain tumour in May 2013. Alvord, a schizophrenic from Michigan, was a prolific thief, molester and kidnapper on the run from a prison sentence for rape when he strangled Ann Herrmann – and then killed Herrmann’s mother and daughter – for the crime of overcharging a friend for a game of pool.

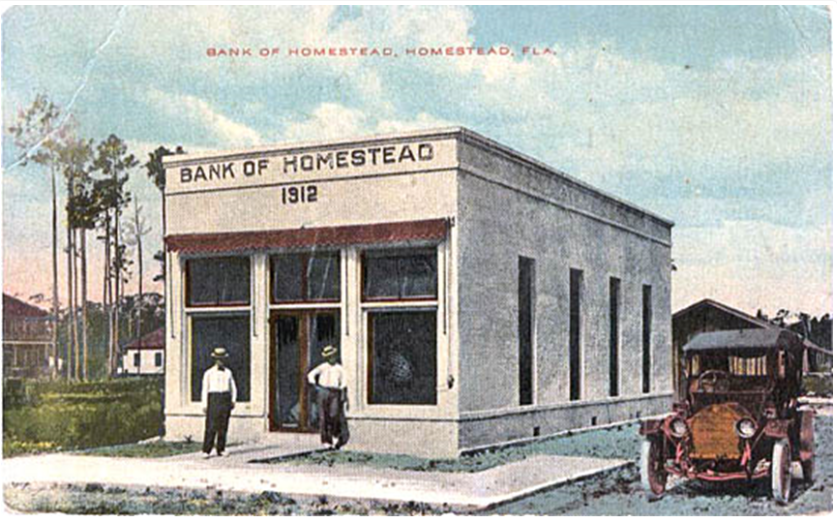

- Florida’s longest-serving prisoner of all, though, was Hugh Alderman – an old-time bank robber whose 62-year stretch in jail began when he was 23 years old, way back in 1917. Alderman was the sole survivor of a four-man gang led by the Rice brothers, Leland and Frank – two experienced career criminals – which held up the Homestead Bank in south Florida on the afternoon of 15 September 1916 and got away with $6,000. They were armed with “automatic shotguns,” and – pursued into the surrounding Everglades swamplands by a posse led by Sheriff Allen Henderson – the gang opened fire, killing three of their pursuers.

The bank at Homestead in the 1920s, a few years after it was robbed.

The resultant manhunt was “without parallel in the history of south Florida,” a newspaper noted at the time, and at least 150 citizens ignored the dangers of being shot – not to mention the discomforts of the heat, humidity, and ever-present swarms of mosquitos – in order to join the hunt. Local residents, meanwhile, hurried to arm themselves and “slept on their guns” for the nearly two weeks that the gang remained at large. Posse members finally caught up with the Rice brothers, separately, on 27 and 28 September. Remembering the fate of their colleagues, the lawmen took no chances, and both robbers were gunned down; Leland Rice was killed and his brother paralysed by a posse bullet. The third gang member, Jim Tucker, drowned swimming a river in his attempt to escape, and Alderman was eventually detected hiding in an empty house, where he surrendered. Narrowly escaping a lynching, Alderman and Frank Rice were taken to Miami, where they went on trial, separately, in 1917. Rice got life, but was paroled nine years later, in October 1926. It seems likely this was because of his deteriorating condition; he died two weeks after his release. But Alderman, who received a life sentence of his own on 8 November 1917, lived on. His time in prison was punctuated by two short-lived escapes – in 1919 and 1924 – but in April 1927 he was transferred to the Florida State Hospital for the insane, where he remained confined until his death on 4 May 1980.

-

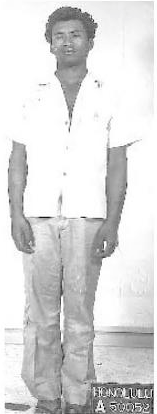

Alfred Tai: shot down a policeman in the wake of an armed robbery.

Hawaii. Armed robber Alfred Tai and his partner Kenneth K. Lono organised the hold-up of the Paradise Cocktail Bar in Kapalama, Oahu, in December 1963, using pistols and carbines they had stolen from the National Guard Armory in Kaneohe two months earlier. Stopped by the police a week after the successful heist, Tai and two confederates – Lono and John Kekai-Requilman Jr. – opted to shoot their way out, killing officers Abraham Mahiko and Andrew Morales. Kekai-Requilman was paroled in 1975 and Lono died, aged 73 and still incarcerated, in 2003, but Tai – a former juvenile offender who had been in trouble with the authorities ever since the age of 10 – served on, to be eventually paroled, aged 72, on 30 June 2014. He had served 51 years of his life sentence.

- Idaho. Sentenced to a short stretch in jail for robbery back in 1969, 21-year-old Ronald Lee Macik was found guilty of killing a fellow inmate during a prison riot two years later. He has violated four paroles, and has a troubled personal history the first saw him enter an institution aged only two. Macik admits lacking all the social skills necessary to survive in the outside world, and as of April 2017, he had completed almost 48 years for the two crimes. He continues to protest his innocence of the prison killing, and has “the lowest inmate number in Idaho, meaning no prisoners who were at the prison when he arrived remain.”

-

Illinois. William Heirens, of Chicago, was a 17-year-old “organised lust killer” when he went to jail for three murders on 5 September 1946; he died on 5 March 2012, still behind bars, still insisting he was innocent, and as the then longest serving prisoner in the world. Heirens earned the soubriquet “The Lipstick Killer” after scrawling the words “For heavens/sake catch me/before I kill more/I cannot control myself” onto the wall of his second victim’s apartment; his original story was that the crimes had been committed by his evil alternate personality, “George Murman.” He was highly intelligent and, having begun college in his home town at the age of 16, was consistently referred to in the press as the “University of Chicago brightboy.” Heirens fought a long battle for freedom, but by early 2011 – the Chicago Reader reported – things were going rapidly downhill for the country’s longest-serving inmate. He “can’t get out of bed or bathe himself,” a reporter wrote, “and his cataract-plagued eyes have left him unable to read. He has severe diabetes and gets shots of insulin twice a day, along with a cocktail of other medications. Nurses constantly change bandages on his legs, where diabetic sores weep fluids. They say he is beginning to show signs of dementia.”

- With Heirens dead, Illinois’s longest-serving prisoner is presently Chester Weger, the Starved Rock Murderer, who confessed in 1961 to the bludgeoning of Lillian Oetting and two other women the previous year.

Chester Weger remains in jail for the murder of three women at Starved Rock, Illinois, in 1960. Their hands had been bound with twine, and a bloodstained branch was found nearby. Weger protests his innocence, but items from the murder scene that he says could prove his case were contaminated; DNA testing is now impossible.

- Entirely unsurprisingly, Indiana‘s record holder is still Van Dyke Grigsby; see above.

-

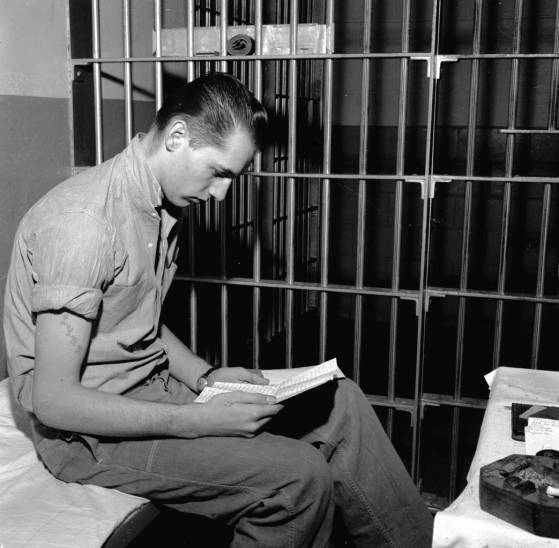

Warren Nutter reads a letter from his mother in his cell.

Iowa. Warren Nutter has spent a lifetime in prison for one moment of vicious stupidity. Convicted of the murder of a policeman in a botched robbery at the age of just 18, Nutter was the youngest person ever sentenced to death in his state, but had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment a year after his February 1956 conviction. The facts of the case were bathetic. Already on the run from a young offenders’ home, and heading for California on an impromptu road trip with five friends, one of them his girlfriend, Nutter decided to raise a little pocket money by holding up a petrol station. An alert patrolman pulled him and his companions over as they made their escape and took them in for questioning. Nutter escaped from the police station through an open toilet window, grabbed a shotgun from his car, and used it to cut down officer Harold Pearce. He was picked up four hours later while attempting to hitch a lift on a nearby highway. According to the statement that he gave to the police: “I remember I didn’t want to leave the others, especially Bette, back there in the police station. I had a shotgun in the car, and then it was in my hands and I was going back into the station. I pointed the gun at the officer…. And the next thing there he was stretched out on the floor and the room was roaring with a gunshot and I was running. I ran and ran. It was like a bad dream – your legs won’t move fast enough and you can’t get away from the thing chasing you. It didn’t take them long to catch me…”

Asked why he had done it, Nutter added: “I wasn’t mad at him… I just… I don’t know why.” Six decades later, that’s still a question with no answer.

-

Kansas. Joe Carr’s crime was murdering a baby. The boy was only six weeks old when Carr threw him into the Arkansas River on 12 September 1941 after telling his wife he was going to find a home for the infant somewhere in Wichita “because we didn’t have any way to take care of it.” Instead, he strangled the baby as he walked towards the river and then dropped the body in. Carr pleaded guilty to murder one week later and repeatedly refused to apply for parole. Jailed on 2 October 1941, he last made the news in 1995, aged 77, but the records of the state’s Department of Corrections reveal that he survived to have parole thrust upon him. He left prison on 13 August 1997, seven weeks short of spending 56 years inside.

- Kentucky. Willie Gaines Smith was Kentucky’s longest-serving prisoner, having swapped an appointment with the electric chair for a life sentence for the murder of a store clerk during a robbery. Smith entered prison on 31 August 1960; his co-defendent was paroled in 1981, but he himself remained in prison as of 2014 despite being granted medical parole because he needed nursing care; no care home would agree to take him in. He died, aged 76, on 14 December 2014, midway though his fifty-fourth year of imprisonment.

Willie Gaines Smith – jailed for murder on 31 August 1960, and denied access to parole hearings in 2004. “I’ve been here long enough,” he told a reporter in 2014. “I’ve served it out.”

- Louisiana. It’s hard to get accurate information out of the Louisiana prison system, but its longest-serving inmate looks likely to be Leotha Brown, who is now in his 70s and went to prison there early in 1964 for robbing and shooting a bartender in a swing club. I’ve found no record of any parole, and Brown was certainly still in the state’s notorious Angola gaol as of 2011, when he featured, playing soprano saxophone, in a documentary on prison music. He appears to have become a model prisoner, running leadership courses, studying for college credits, and assisting at the Angola Bible College. If he is indeed still in jail, Brown is [April 2017] currently approaching the end of his 53rd year inside.

-

Maine. French-Canadian Albert Paul, a thief, killer and prolific escapee, is the oldest and the longest-serving prisoner in Maine. He first went to prison aged 18 in the early 1950s, but says he has “lost the fire” for trying to break out and accepts that he will die in jail. The state estimates that it has paid $1.5m to keep him incarcerated over the past 64 years, and his current sentence, for a murder he now says he did not commit, began in 1971, meaning that – as of April 2017 – Paul was 83, and 45 years into his latest stretch. The secret to serving time, he says, is to distance oneself from the outside world as much as possible. “There’s two worlds: free world and prison world, you know?” he told a reporter who became his first visitor in 13 years. “I don’t want people visiting me saying, ‘Oh, we was down at the beach over the weekend.’ I don’t want to hear that kind of talk. I can’t go to the beach. You see?” (Portland Press-Herald, 13 April 2013)

- Maryland. Charles Edret Ford launched a highly unusual appeal against his murder conviction in July 2015 – unusual in that the prosecutor and all the witnesses who featured in his 1952 trial were long dead, there was no trial transcript, and almost all of the records relating to it had been destroyed around 2009. Ford, who is black, had been convicted by an all-white jury of the shotgun murder of one Vincent Lewis (who had, in turn, apparently killed Ford’s brother). He claimed to know the identity of the real murderer, but declined to reveal it, adding that both he and his girlfriend were coerced into making confessions by an officer who hit him in the face with his night stick. Ford did have an alibi – he said he and his girlfriend were with another brother at a dance – and there were also discrepancies in witnesses’ descriptions of the killer, one stating that he wore a light coat and dark trousers, another that the colours were the other way around. By the time the appeal was lodged, Ford was suffering from cancer and showing early signs of dementia; as a result, he was released from prison into the care of the Blue Point Nursing Rehabilitation Centre in December 2015, and a few months later, his attorneys managed to have the murder conviction discharged on the grounds that the judge had failed to apprise the prisoner of his post-trial rights. That still left the problem of a second conviction, for assault, which had been incurred in the course of a furlough Ford had been granted in 1975; the judge dealt with that by changing the sentence on the second offence to one of five years, all suspended. Ford, who was aged 84 at the time of his release, wept tears of joy on hearing he would be freed, and told a reporter his main aim now was “to live as long as I can, as happy as I can.” One sidelight is that the modest publicity surrounding the appeal led Ford’s great-niece to surface and establish contact with him – shades of the Richard Honeck case.

-

Jesse Pomeroy, before and after: aged 15 in 1874, at the time of his conviction, and aged 69 in 1929, 54 years into his stretch. The latter photograph was snatched as the child-killer was being transferred to Massachusetts’s state mental hospital.

Massachusetts. They called him ‘The Boston Boy Fiend,’ and he really was a child. Jesse Pomeroy, who went to prison for two murders back in 1874, then aged 15, still holds his state’s record for the longest sentence served, having survived into his early 70s and completed very nearly 58 years in the pen. Pomeroy had begun his criminal career years earlier, when he was only 12. The child of an abusive father, and possessed of a strangely unforgettable face – one eye was milk-white and regularly described in the contemporary press as ‘like a marble’ – the young Pomeroy enjoyed torturing animals and soon graduated to beating up much younger boys. His earliest victim, William Paine, was only four years old when he was waylaid, brutally assaulted, and left suspended from a beam in an abandoned cottage. Nearly a dozen other similar attacks followed, but in September 1872 Pomeroy’s luck ran out when he walked into a police station house at the same time as one of his victims, and was promptly identified and sentenced to juvenile detention. Pomeroy’s record was so good that he was released only a year and a half later, but it took only a matter of weeks for him to return to his old ways. His first murder was committed in March 1874 when a 10 year old girl, named Katie Curran walked into the Pomeroy family’s store hoping to buy a notebook. The boy – by then 14 – took her down to the cellar, where he cut her throat with his penknife and hid her body beneath a pile of rubbish. A second equally violent and senseless killing followed the next month; this time the victim was a boy of four. Discovered shortly afterwards, when the cellar in which Curran had been interred was dug up to be redeveloped, Pomeroy was sentenced to death that same December, only to have his sentence commuted to life because of his age. Instead, he served out an astonishing 41 years in solitary confinement before being switched to general population in 1917. Just over a decade later, he transferred to the Bridgewater Hospital for the Criminally Insane, where he died, aged 72 and still incarcerated, on 29 September 1932. Pomeroy was, it seems, highly intelligent – he wrote an autobiography and taught himself several languages while in jail – and (so the Boston Globe reported) he made at least a dozen unsuccessful escape attempts during his years in solitary. His story has been told twice in book form, by Harold Schechter and Roseanne Montillo.

-

Michigan. Armed robber Clarence Marshall was paroled on 27 January 2015, 64 years and two months into his jail sentence – edging out by about one month the time served by Richard Honeck, and making him one of the top ten longest-serving prisoners that I know of. He is also by far the most obscure. For reasons that escape me, Marshall’s case remains almost entirely unreported; despite searching, I have found no press coverage of either his conviction or of his release. What we do know is that he received a sentence of life for two counts, one of armed robbery in September 1952 and another of an unarmed “assault with intent to rob and steal” in November 1950. He was born on 18 May 1930, making him 84 years old at the time of his parole.

Oliver Terpening before and after (1947 and 2010): murder disappointed him, but he had 63 years to reflect on why.

- Marshall’s stretch beat out the time served by another old Michigan lag, Oliver Terpening, who murdered a schoolfriend and the boy’s three sisters in May 1947 for no better reason than that he wanted to find out what it felt like to kill another human being. Terpening – a farmboy who was then just 16 years old – and his neighbour Stanley Smith, 14, were on a can-shooting and wildflower hunting expedition near Imlay City when Terpening shot Smith through the back of the head with a hunting rifle. “I’ve always kinda wondered what it would be like to kill somebody,” he later said. “I just wanted to see someone die.” According to the prosecutor who tried him, Terpening then attempted to rape Barbara Smith, also 16, but was interrupted by her sisters Gladys, 12, and Janet, 2. “I thought the best thing to do was to kill them all,” he concluded; after murdering the three girls, he pressed flowers into their hands, went home for dinner, and then tried to make a break for it in the family car. He got as far as Detroit before being picked up by the police. The judgement of a panel of psychiatrists, who argued that Terpening was mentally unbalanced, was overturned, and he was found to be sane and sent to prison. He spent more than 63 years behind bars, dying, still incarcerated, on 29 October 2010. At the time of the killing, Terpening expressed disappointment that he “didn’t get the thrill I expected.” (Mexia Weekly Herald, 27 June 1947) By 1982, he had apparently repented, telling a newspaperman who came to see him in the Jackson pen: “It’s something I never get away from – the memory of it. It’s probably the hardest thing in the world to live with.” But he had decided against suicide: “Actually, although I’m in prison, I’m a free man. I’m my own person, despite the guns and the walls and the guards… I have a cell where I can watch the sunset. It has its rewards – even in here.” (Ludington Daily News, 4 May 1982)

- That leaves Sheldry Topp. After more than 50 years behind bars, he has only hazy memories of the day he stabbed an attorney named Charles Davies in the chest and neck while burglarising the man’s home back in 1962. Topp was 17 years old, and on the run from the state mental hospital at Pontiac, at the time. While he fled the house before his victim died, he had fatally exacerbated the situation by dismantling Davies’s phone at the start of the break-in, preventing the dying man from calling for help. Topp now claims to be remorseful – though he adds, “I never understood how people go about showing remorse. I could break down and cry and so forth. People say that’s crocodile tears. I could yell and scream, and people would say that’s putting on a show” – and eight of the 10 parole board members who heard his case in 2011 recommended him for release. His request was denied by Michigan’s governor, Jennifer Granholm.

-

Morse: served 42 years for serial murder.

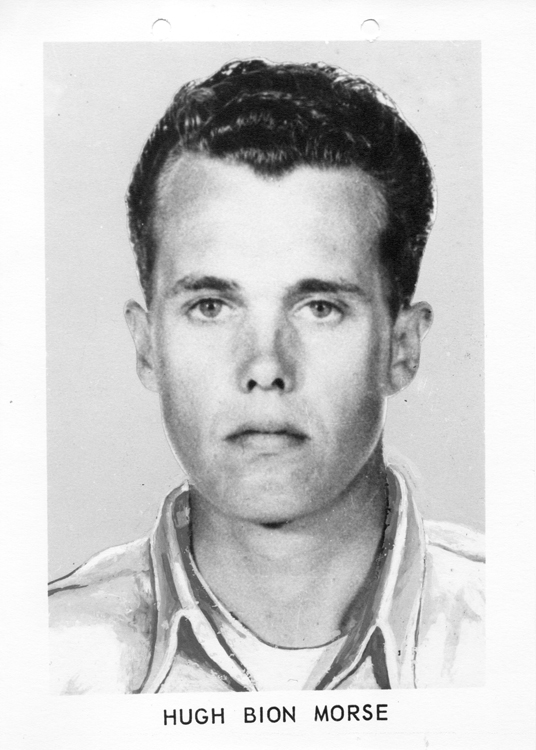

Minnesota. The only serial killer on this listing is Kansas City-born Hugh Bion Morse, a deeply unpleasant “rape-slayer” who killed at least four women. Morse was picked up in Minnesota on a fugitive warrant in the summer of 1961 after attempting the murder of his wife in California and raping and killing Carol Ronan in her own home in St Paul. He confessed to strangling two other women in Spokane, Washington, but it emerged only 20 years later that he had also bludgeoned a fourth victim to death with a lead pipe in Birmingham, Alabama, that same August. Morse, who was dishonourably discharged from the Marines, had a rap sheet dating back to 1951 that included assaults against women, indecent exposure, and child molestation involving girls as young as 6; in addition to being lead suspect in other, unsolved, murders, he was also responsible for several rapes in Georgia, a long series of burglaries in California, and, said the Chicago Sunday Tribune (15 Oct 1961), of “making obscene proposals to women over the telephone at Burbank, Cal.” At one point during the manhunt for him, he was picked up on suspicion of voyeurism and released on $200 bail, unrecognised by cops who failed to notice his resemblance to the man on the Wanted poster pinned to the wall behind them. Morse eventually served a little under 42 years of a life sentence, beginning in October 1961; he died in jail in April 2003. His was a miserable existence; he told police: “I can’t remember being happy any time since I was born.”

- Mississippi. Ernest (or Earnest) Lee Wilson had already been inside for six years, serving life, when he stabbed another prisoner, trusty Luther Wadley, to death while Wadley was sitting in a prison barber’s chair. That was on 3 September 1970; three years later, Wilson made a short-lived escape, but he was recaptured and remained incarcerated long enough to be listed as his state’s longest-serving prisoner late in 1994. By then he had completed 30 years inside, and was still only aged 51 or 52. I have found no further record of him and he is no longer incarcerated, but – given his youth and the double murder sentences he had received, I assume that he most likely both survived and remained in prison long enough to beat the time served by his state’s current record-holder…

Captured – Richard Gerald Jordan is paraded in handfuffs at the height of the fashion-conscious 1970s.

- … Richard Gerald Jordan, who in January 1976 murdered a woman he had kidnapped after demanding a $50,000 ransom for her, and remains incarcerated at Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Farm facility after 39 years – most recently after a judge halted a further attempt to execute him in order to investigate whether death by lethal injection constituted cruel and unusual punishment. As of April 2017, Jordan was coming up to 71 and remains the longest-serving inmate on the state’s death row.

- Missouri. Earl George was a middle-aged farmer in Grovespring, Missouri, back in 1947 when – he said – his wife “started at him with a butcher knife” while he was drying dishes. He retaliated by picking up a double-headed axe that he had lying about the kitchen and splitting open her head with it. George already had a record – he had been adjudged insane two years earlier after some hazily-described sexual encounter with a neighbour’s mare, and had spent time in six insane asylums in Missouri and Nevada. He remained incarcerated as late as the autumn of 1994, 47 years later, the last time I have record of his case. He would have been 94 years old by then.

- Nebraska. Few of the killers on this list proved to be more desperate or dangerous than Jerry Lee Hansen, Nebraska’s longest serving inmate, who went to jail on 20 May 1965 for the triple shooting of his wife and her parents in Cedar Bluffs. Both in-laws were killed and his wife was maimed in the attack, which took place within a few hours of Hansen bring served with divorce papers. Allowed out of jail to attend an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in 1973, Hansen persuaded his guard to let him call on his by then former wife. He then attacked the prison officer and tied him up before using the man’s gun to shoot his wife for a second time. This time Sandra Soderling was paralysed, and her ex-husband picked up a second 20 year sentence for wounding her, to add to the one he had been handed in 1965. As of April 2017, Hansen had been in jail for almost 52 years.

-

Raymond Shuman is booked for double murder just before Christmas 1957. Shuman is still held in a Nevada jail almost six decades later.

Nevada. Raymond L. Shuman, 23, was convicted of double murder on 13 June 1958 for his involvement in the robbery and killing of a truck driver and an electrician in the course of a “tri-state crime spree” that took place the previous December while he and an accomplice were both AWOL from the US Navy. Shuman and his fellow sailor Melvin Rowland (who actually pulled the trigger), got a pathetic $3 from the body of their second victim. He remains in prison with [April 2017] almost 59 years served, and has been no model prisoner. In 1973, he doused another inmate with lighter fluid and set him on fire in the course of a fight over whether the window near his cell should be open or closed.

-

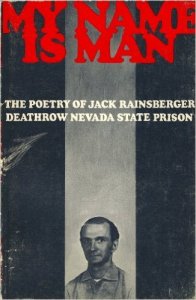

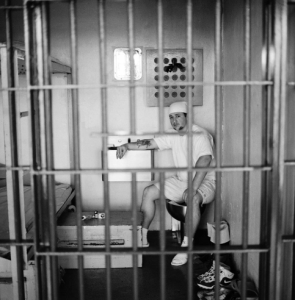

Nevada’s second longest serving inmate was Jack Rainsberger, jailed in March 1959 for the murder of a Las Vegas secretary, Erline Folker. He served 41 years and made 20 applications for parole before being released, aged 65 and by that time in a wheelchair, in September 2000. During his years in prison – the first 13 of them spent on Death Row, awaiting an appointment with the gas chamber – Rainsberger became a published poet. “You have two choices,” he told one newspaper in 1973. “You could look to be executed and live for that. Or you could go about your business as though the execution did not exist… I live as if I was going to continue to live. I adopted the Vandanta School of Hinduism. I studied.” None of this cut much mustard with Folker’s son, who campaigned for many years for his mother’s killer to remain behind bars for life.

-

New Hampshire. Axe murderer Walter H. Bourque Jr. was convicted in December 1955 of killing a four year old girl, Patricia Johnson, and sentenced to a term of 18 years to life. Bourque was 17 at the time, and was reported in 2004 to be institutionalised, having apparently never been enrolled on the sex offender programme he had been told in 1999 to complete before he could be considered for release. Bourque flirted with freedom on several occasions – in 1977 he was on some form of day-release from a minimum security unit when he was accused of “inappropriate conduct with minors” and returned to jail, and in 1978 or 1979 he was out again on a short-term pass, but caught stealing a cheque. I have been able to find no firm news of Bourque since his case was in the press in July 2004, at which point he had completed more than 49 years in jail, but the New Hampshire Department of Corrections Inmate Locator lists him as still incarcerated and due for release on or before 11 June 2054. He completed his sixtieth year in jail on 10 December 2015.