Early on the morning of 18 February 1848, two men and a woman walked into the square in front of the Porte de Hal, in Brussels, where a public execution was due to take place shortly after dawn. They were there to conduct a ground-breaking scientific study, and, by prior arrangement with the Belgian penal authorities, were permitted to climb onto the scaffold and wait next to the guillotine at the spot where the severed heads of two condemned criminals were scheduled to drop into a blood red sack.

One of the men was Antoine Joseph Wiertz, a well known Belgian painter and also a fine hypnotic subject. With him were his friend, Monsieur D_____, a noted hypnotist, and a witness. Wiertz’s purpose on that winter’s day was to carry out a unique and extraordinary experiment. Long haunted by the desire to know whether a severed head remained conscious after a guillotining, the painter had agreed to be hypnotised and instructed to identify himself with a man who was about to be executed for murder.

Wiertz – the plan went – ‘was to follow [the murderer’s] thoughts and feel any sensations, which he was to express aloud. He was also ‘suggested’ to take special note of mental conditions during decapitation, so that when the head fell in the basket he could penetrate the brain and give an account of its last thoughts.’ [Shepard II, 648] And, incredible as it may seem to us, his scheme appeared to work – indeed, it worked rather too well. As soon as the tumbrel carrying the condemned men to their deaths appeared, Wiertz began to panic. ‘It seemed to the painter that the guillotine’s blade was cleaving his own flesh. It crushed his spine and tore his spinal cord.’ It was not until killers ascended the scaffold that Wiertz recovered himself sufficiently to ‘ask Monsieur D to put me in rapport with the cut off head, by means of whatever new procedures seemed appropriate to him… He made some preparations and we waited, not without excitement, for the fall of a human head.’

As the large crowed watched for the fatal moment, though, it became clear that the painter was still identifying all too closely with his subject’s extreme predicament. Wiertz ‘became entranced almost immediately and… manifested extreme distress and begged to be demagnetised, as his sense of oppression was insupportable. It was too late, however – the knife fell.’ [Wiertz pp.491-2; Benjamin p.250; Shepard op.cit.]

The Porte du Hal, Brussels. Once part of the city walls, later a prison, and in 1848 site of Wiertz’s unusual experiment with a severed head.

We’ll return to Antoine Wiertz and his severed head in a moment. First, though, let’s sketch in a little of the background of this unfortunately macabre tale. Versions of the implement we now know as the guillotine have been around for hundreds of years – since the 1520s at least, and arguably as early as the first years of the fourteenth century. [Laurence p.70] For much of that time, and certainly since the name of Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin became indelibly associated with it at the time of the French Revolution, there has been speculation as to just how painless and how quick death by this invention really is. It’s fair to say that – at least among that small handful who have given the subject proper thought – there has long been a suspicion, amounting in some cases to near certainty, that a head may retain consciousness, however briefly, after its severing. The subject was considered as early as 1796 in a French pamphlet, Anecdotes sur les Décapités, and again, briefly, in English, by John Wilson Croker in his History of the Guillotine (1853). Doctors, for the most part, insisted that the shock of the blade must cause immediate unconsciousness, and that loss of the blood supply to the brain brings on actual death a matter of seconds later – there is a cardiologists’ maxim that when a heart stops, the brain can retain consciousness for no more than four seconds if the person concerned is standing, eight if he is sitting, and 12 if he is lying down. That implies that any movements of a detached noggin’s eyes or lips “are merely convulsive, and that the severed head does not feel.” [Wilson p.115] But, over the years, a small and frankly dubious body of evidence has accumulated to suggest this view is wrong, and that – in a handful of cases at least – the severed head remains aware of what has happened to it.

There’s no denying that this awful thought is gruesomely compelling, in much the same way as is the idea of being buried alive. It has a “My God, what if that happened to me?” quality about it. And, while it was never Guillotin’s intention to do anything other than supply a humane alternative to the notoriously slow and painful business of executing criminals by rope or axe (and hardly the good doctor’s fault that the fascination of a device designed solely to kill makes the guillotine – like the gas chamber and the electric chair – at least as horrifying as a gallows in its own mechanically ingenious way), the fact remains that the device became a victim of its own success. It was so quick, so clean, so bloodily final that it was hard for an execution-going public accustomed to the protracted struggles of a hanged man to believe that life could be extinguished quite so swiftly.

Murky and unsubstantiated rumours concerning the survival of consciousness in severed heads swirled through France throughout the nineteenth century, and it is not hard to find versions of the same stories today in the less reputable crannies of the internet. For example, tall tales about at least two of the guillotine’s most noted victims abound: Lavoisier, the chemist, is supposed to have agreed with an assistant that he would blink as many times as he could after his execution in 1794 – and the assistant is said to have counted 15 or 20 blinks, at the rate of one a second. Similarly, when the executioner held up the head of Charlotte Corday, who had stabbed Marat in his bath, and delivered a sharp slap to its cheek, the head is said – on the authority of one Dr Sue – to have blushed and displayed “unequivocal marks of indignation.” [Croker p.70; Gelbart p.201] Neither story, though, rests on a solid contemporary source.

Despite such early manifestations of interest in the subject, moreover, it remains equally difficult to uncover reputable sources for several nineteenth- and early twentieth-century incidents in which doctors are popularly believed to have conducted some gruesomely suggestive experiments to finally answer the question. Accounts of several such experiments can be found in the secondary literature – see, for example, Richard Zacks’s influential counterculture classic An Underground Education – and most texts mention tests supposedly done on the head of “a necrophile rapist by the name of Prunier,” or the story of an unnamed doctor who took an unknown head and pumped it full of blood from a vivisected dog. The cultural historian Philip Smith, who dissects several such tales, suggests they form little more than “a stubborn counter-discourse of wild speculation and morbid popular inquiry” [Smith p.139] – and he has a valid point, for the most part. Yet some quite extensive digging does eventually reveal that at least three sets of experiments on severed heads apparently were carried out in France between 1879 and 1905, albeit with less than spectacular results. Since these cases form a useful counterpoint to the experiences of Antoine Wiertz, it seems a good idea to summarise them briefly here.

• On 13 November 1879, a father-and-son duo, Drs E. and G. Descaisne, witnessed the execution of Théotime Prunier, who had been found guilty of the rape and subsequent murder of an elderly woman at Beauvais. A report in the British Medical Journal, 13 December 1879, notes that the doctors were given ready access to the killer’s head and “tried certain experiments” on it, concluding: “We have ascertained, as far as it is humanly possible to do so, that the head of the criminal in question had no semblance whatever of the sense of feeling; that the eyes lost the power of vision; and, in fact, the head was perfectly dead to all intents and purposes.” A fuller report, published in the Gazette Médicale de Paris, noted some of the tests the doctors subjected the head to: shouting “Prunier!” in the dead man’s ear, pinching his cheek, inserting a brush soaked with ammonia into his nostrils, pricking the face with needles, and holding a lighted candle to an eyeball. Since secondary sources invariably stress that these experiments were conducted only moments after Prunier’s head was severed, the complete lack of any response might be considered good evidence for the conventional medical view that shock causes instant unconsciousness and death. The key detail in this instance, however, is one reported by the BMJ: the doctors took charge of the killer’s head only “about five minutes after the execution.” This suggests that the experiments must be regarded as inconclusive; even the most optimistic proponent of the idea that a head remains briefly alive after severing rarely suggests that consciousness endures for more than 15 or 20 seconds at best. [Evrard & Decaisne pp.629-30; Verplaeste p.372; Gerould p.55]

• A year later, in September 1880 – at least according to the later account of a certain Dr Dassy de Lignères, of whom nothing else seems to be known – some experiments were conducted on the head of a particularly unpleasant murderer named Louis Ménesclou. Ménesclou, 19, who had lured a little girl into his room with a spray of violets, raped her and killed her, was a man “of limited intelligence… frequently guilty of sexual perversity” – as suggested by the fact that he then dismembered his victim; parts of her body were found in his pockets. [London Evening News, 15 October 1888; Stewart] In this case, apparently, Dassy de Lignères was provided with his head three hours after the execution, and claimed to have connected the principal veins and arteries to a supply of blood provided by a living dog. A quarter of a century later, when the doctor gave an interview to the French newspaper Le Matin (3 March 1907), he claimed that colour almost immediately returned to the face, the lips swelled and the dead man’s features “sharpened.” Perhaps. What’s really incredible is Dassy de Lignères’ insistence that “as the transfusion proceeded, suddenly, unmistakably, for a period of two seconds, the lips stammered silently, the eyelids twitched and worked, and the whole face wakened into an expression of shocked amazement. I affirm… that for those two seconds, the brain thought.” This reads as either spectacularly shoddy research or, more likely, simple sensationalism on the part of either the doctor or the newspaper.

• Finally, on 30 June 1905, Dr Gabriel Beaurieux obtained permission to attend the guillotining of Henri Languille, a “bandit who had terrorised the Beauce and the Gatinais [in the valley of the Loing, between Paris and Orléans] for several years.” [Morain p.300] His report concluded that Languille retained some form of consciousness for about half a minute after his execution:

“The head fell on the severed surface of the neck and I did not therefore have to take it up in my hands, as all the newspapers have vied with each other in repeating; I was not obliged even to touch it in order to set it upright. Chance served me well for the observation which I wished to make.

“Here, then, is what I was able to note immediately after the decapitation: the eyelids and lips of the guillotined man worked in irregularly rhythmic contractions for about five or six seconds. This phenomenon has been remarked by all those finding themselves in the same conditions as myself for observing what happens after the severing of the neck…

“I waited for several seconds. The spasmodic movements ceased. The face relaxed, the lids half closed on the eyeballs, leaving only the white of the conjunctiva visible, exactly as in the dying whom we have occasion to see every day in the exercise of our profession, or as in those just dead. It was then that I called in a strong, sharp voice: “Languille!” I saw the eyelids slowly lift up, without any spasmodic contractions – I insist on this peculiarity – but with an even movement, quite distinct and normal, such as happens in everyday life, with people awakened or torn from their thoughts.

“Next Languille’s eyes very definitely fixed themselves on mine and the pupils focused themselves. I was not, then, dealing with the sort of vague dull look without any expression, that can be observed any day in dying people to whom one speaks: I was dealing with undeniably living eyes which were looking at me. “After several seconds, the eyelids closed again, slowly and evenly, and the head took on the same appearance as it had had before I called out.

“It was at that point that I called out again and, once more, without any spasm, slowly, the eyelids lifted and undeniably living eyes fixed themselves on mine with perhaps even more penetration than the first time. The there was a further closing of the eyelids, but now less complete. I attempted the effect of a third call; there was no further movement – and the eyes took on the glazed look which they have in the dead.

“I have just recounted to you with rigorous exactness what I was able to observe. The whole thing had lasted twenty-five to thirty seconds.” [Anon, ‘Revue des journaux…’]

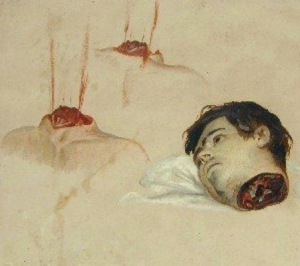

This is the best – indeed the only apparently credible, medically attested – evidence for the survival of any sort of consciousness in the head of an executed man, so it is important to note that the anonymous author of the Bois De Justice site, which features some excellent research into the history of the guillotine, questions whether the experiment on Languille actually took place as claimed. There are at least two reasons to doubt accounts of this execution: first, a widely circulated photo [above right] showing the condemend man standing by the guillotine is, in fact, a clumsy fake, with the figures painted in; second, the doctor’s presence is not mentioned in contemporary newspaper coverage, and Beaurieux’s account does not mesh with the actual photos taken on the day, which show no horizontal surface on which the severed head could possibly have fallen before it entered the waiting bucket. To have conducted his experiment, the doctor would have had to pull the head from the bucket by hand.

Bearing those mixed results in mind, then, let’s return to the Porte de Hal in Brussels in February 1848 (and you’ll note that the experiments of Antoine Wiertz predated all three of the French experiments outlined above.) According to Wiertz’s biographer, the subject of his study was a nasty and incompetent burglar by the name of François Rosseel, who had – with his accomplice Guillelme Vandenplas – broken into the apartment of Rosseel’s landlady, Mlle. Evanpoel, the previous September and bludgeoned her and two female servants to death for the sake of a few hundred francs. This crime horrified all Belgium, and Wiertz followed the resulting newspaper coverage intently, suggesting that his choice of the double execution of Mlle. Evanpoel’s murderers for his experiment was a deliberate one. [Anon, Causes Célèbres… I, 109-16; Annales de l’Université de Bruxelles pp.173-5; Van der Haeghen, V, 94; Watteau p.232; Metdepenningen]

As Rosseel’s head rolled into the sack in front of him, anyway, the hypnotised Wiertz was asked to place himself inside the dying brain. The description that follows is drawn from the text that the artist himself wrote to accompany a triptych that he later painted to illustrate his experience, which was, in turn, incorporated into that work in the form of a painted inscription on a trompe-l’oeil frame and printed, later, in the first catalogue of his work. The description is rather long and rather overwrought, and part of it is in the first person, as Wiertz describes what he identifies as Rosseel’s own final thoughts. It has been somewhat abbreviated here, and several sharply differing versions of the text have been merged as best I am able to reconcile them. [Watteau pp.132-41; Benjamin pp.250-2; Shepard II, 648]:

Monsieur D_____ took me by the hand… led me before the twitching head, and asked: ‘‘What do you feel? What do you see?’ Agitation prevented me from answering him on the spot. But right after that I cried in the utmost horror: “Terrible! The head thinks!” … It was as if an oppressive nightmare held me in its spell. The head of the executed man thought, saw, suffered. And I saw what he saw, understood what he thought, and felt what he suffered. How long did it last? Three minutes, they told me. The executed man must have thought: three hundred years.

What the man killed in this way suffers, no human language can express. I wish to limit myself here to reiterating the answers I gave to all the questions during the time that I felt myself in some measure identical to the severed head.

First minute: On the scaffold

A horrible buzzing noise… It’s the sound of the blade descending. The victim believes that he has been struck by lightning, not the axe.

Astonishingly, the head lies here under the scaffold and yet still believes it is above, still believes itself to be part of the body, and still waits for the blow that will cut it off.

Horrible choking! No way to breathe. The asphyxia is appalling. It comes from an inhuman, supernatural hand, weighing down like a mountain on the head and neck… Oh, even more horrible suffering lies before him.

A cloud of fire passes before his eyes. Everything is red and glitters.

Second minute: Under the scaffold

Now comes the moment when the executed man thinks he is stretching his cramped, trembling hands towards the dying head. It is the same instinct that drives us to press a hand against a gaping wound. And it occurs with the intention, the dreadful intention, of setting the head back on the trunk, to preserve a little blood, a little life.

Delirium redoubles his strength and energy.

In his imagination, it seems that his head is on fire and spins in a dizzying motion, that the universe collapses and turns with it, that a phosphorescent liquid swirls around and merges with his skull… In a moment more, his head is plunging into the depths of eternity.

But is it only the body that writhes and cries out in anguish, which produces the torture suffered by the guillotine? No, because here comes the intellectual and moral agony. The heart, which beats in his chest, is still beating in the brain.

That’s when a crowd of images, each more terrible than the others, crowd into a soul beaten by the fiery breath of nameless pain. The guillotined head sees his coffin, sees his trunk and limbs collapse, ready to be enclosed in the wooden box in which thousands of worms are about to devour his flesh. Physicians explore the tissue of his neck with the tip of a scalpel. Every nick is a bite of fire.

He sees his judges, too… They sit well served at a table, talking quietly of business and pleasure…

The exhausted brain sees… the smallest of his children close to him. Oh! he likes that. That’s him: his hair blond and curly, his little cheeks round and pink … And meanwhile, he feels the brain continue to sink and feels sharp stabs of pain…

Third minute: In eternity

It is not yet dead. The head still thinks and suffers.

Suffers fire that burns, suffers the dagger that dismembers, suffers the poison that cramps, suffers in the limbs, as they are sawn through, suffers in his viscera, as they are torn out, suffers in his flesh, as it is hacked and trampled down, suffers in his bones, which are slowly boiled in bubbling oil. All this suffering put together still cannot convey any idea of what the executed man is going through.

And here a thought makes him stiff with terror:

Is he already dead and must he suffer like this from now on? Perhaps for all eternity?…

No, such suffering cannot endure for ever; God is merciful. All that belongs to earth is fading away. He sees in the distance a little light glittering like a diamond. He feels a calm stealing over him. What a good sleep he shall have! What joy!

Human existence fades way from him. It seems to him slowly to become one with the night. Now just a faint mist – but even that recedes, dissipates, and disappears. Everything goes black… The beheaded man is dead.

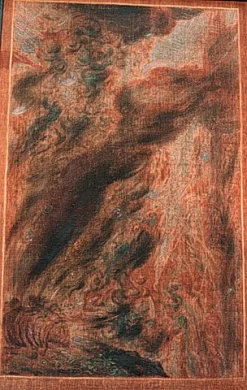

It is difficult to know how best to handle Wiertz’s bizarre evidence. How much of his remarkable experience was noted down at the time remains uncertain; the painter did not actually produce the strange triptych he entitled Dernières pensées et visions d’une tête coupee (Last Thoughts and Visions of a Decapitated Head) until five years later, in 1853, so he had plenty of time to think through the events of 1848 again and again, perhaps so often that his recollections became distorted, romanticised, exaggerated and unreliable – if they ever were reliable in the first place, that is.

Wiertz’s impressions, too, were so vivid, so melodramatic, that it not hard to believe that they did not come to him as he penetrated a dying brain, but were actually generated somewhere deep within his own morbid imagination. For this, after all, was a painter whose works scandalised contemporaries, and is nowadays pretty much ignored (the Musée Wiertz, in Brussels, based in the painter’s old studio, currently averages no more than 10 visitors a day, “many of them dragooned in school parties.” [Anon, ‘A Belgian national champion’]). A look at some of his other works certainly reveals an obsession with death; they include Two Young Ladies (which depicts a naked beauty contemplating a skeleton), Premature Burial (in which an anguished figure bursts from a coffin lying in a crypt) and – perhaps the most over-the-top of many over-the-top creations – Ravishing of a Belgian Woman. In this last painting, as one critic remarks, “Wiertz breaks with convention by equipping his heroine with a pistol (although not with any clothes). She duly shoots the soldier molesting her, causing his head to explode, an event Wiertz depicts in gory detail.” [Ibid]

Last Thoughts and Visions of a Decapitated Head survives, although in a sadly decayed state; it was painted in an experimental style that has not stood up at all well to the passage of the years. A close look at its three panels reveals that they correspond quite closely to the description Wiertz left of his experiences on the Brussels scaffold. Rosseel’s severed head can be seen tumbling down in the bottom right hand corner of the central panel, and, in the third and final portion of the triptych, the murderer’s slide into eternity can still just be discerned.

And if Antoine Wiertz’s pioneering experiment remains little more than an enigmatic anomaly, and he himself is long forgotten, there is at least a delicious irony in the tail end of his career. A few years before his death, while at the height of his fame, Wiertz wrote to the Belgian government, offering to exchange 220 of his largest and most gaudy paintings for a “huge, comfortable and well-lit studio” to be funded by the state. Remarkably, the interior minister of the day agreed to this presumptuous request, though the government baulked at the idea of setting Wiertz up in expensive premises in the centre of the capital.

Instead, the painter was provided with a new studio in a cheap and dismal suburb, albeit one that the artist cheerfully predicted might someday become “the centre of an immense and rich population.” He may have been a rotten painter, wrong about hypnotism, and wildly out of his depth in experimental parapsychology, but Antoine Wiertz was at least right about that. Today, the little-visited Musée Wiertz stands no more than 20 metres from the very centre of Europe, in the shape of the gleaming towers of the European Parliament. And that monolith’s address? The Parliament stands proudly on Rue Wiertz.

Anon. ‘A Belgian national champion.’ The Economist, 9 July 2009.

____. Annales de l’Université de Bruxelles: Faculté de Médecine. Brussels: Université Libre, 1880.

____. Causes Célèlebres de Tous les Peoples. Brussels: Libraries Ethnographique, 1849.

____. La Belgique Judiciaire: Gazettes des Tribunaux Belges et Étrangers. Brussels, np. Volume 9, 1851 .

____. ‘Letters, notes, and answers to correspondents.’ British Medical Journal, 10 January 1880.

____. ‘Revue des journaux et sociétés savantes. Exécution de Languille. Observation prise immédiatement après décapitation. Communiquée à la Société de médecine du Loiret le 19 juillet 1905…’ Archives de l’Anthropologie Criminelle, de Criminologie et de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique. Volume 20 (1905) pp.645-54.

____. ‘Special correspondence. Paris.’ British Medical Journal, 13 December 1879.

____. ‘Special correspondence. Paris.’ British Medical Journal, 13 December 1879.

‘A medical man’. ‘A theory of the Whitechapel murders.’ Evening News, 15 October 1888.

M. Auberive. Anecdotes sur les Décapités. Paris: Sobry, 1796.

Walter Benjamin. The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Cambridge [MA]: Harvard University Press, 2008.

John Wilson Croker. History of the Guillotine. Revised from the ‘Quarterly Review’. London: John Murray, 1853.

Evrard & G. Decaisne. ‘Expériences physiologiques sur un décapité.’ Gazette Médicale de Paris, 1879.

Nina Rattner Gelbart. ‘The blonding of Charlotte Corday.’ Eighteenth Century Studies vol.38 (2004).

Nina Rattner Gelbart. ‘The blonding of Charlotte Corday.’ Eighteenth Century Studies vol.38 (2004).

Daniel Gerould. Guillotine. Its Legend and Lore. New York: Blast Books, 1993.

Louis Labarre. Antoine Wiertz: Etude Biographique Avec les Lettres de l’Artiste et la Photographie du Patrocle. Brussels: Muequardt, 1867.

John Laurence. A History of Capital Punishment. New York: Citadel Press, 1960.

Marc Metdepenningen. ‘L’effroyable triple crime de la place Saint-Géry.’ Le Soir (Brussels), 12 July 2006.

Alfred Morain. The Underworld of Paris: Secrets of the Sûreté. London: Jarrolds, 1930.

Leslie Shepard [ed]. The Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Detroit: Gale Research, 1984.

Philip Smith. Punishment and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Harry E. Stewart. ‘Jean Genet’s favourite murders.’ The French Review vol.60 no.5 (1987)

Ferdinand Van der Haeghen. Bibliographie Gantoise. Recherches Sur la Vie et les Travaux des Imprimeurs de Gand (1483-1850). Ghent: privately published, 1860.

Jan Verplaetse. Localizing the Moral Sense: Neuroscience and the Search for the Cerebral Seat of Morality, 1800-1930. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009.

Antoine Joseph Wiertz. Oeuvres Littéraires. Brussels: Parent et Fils, 1869.

Louis Watteau. Catalogue Raisoné du Musée Wiertz. Brussels: Musées Royeux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 1865.

Andrew Wilson. ‘Leaves from the notebook of a naturalist.’ Part X. The Living Age, vol.31, 1851.

Can’t be arsed reading all that. What happened?

Hey! Look at that shiny thing over th

head chopped off, faces moved, dr did study

Was an interesting read. The fact that the guy convinced people he could perceive what the severed head was feeling and seeing is amazing.

I wish I could go back in time with the knowledge I have today, I would fuck with people endlessly.

If people can be con-vinced there is a god why not this?

You ever entertain the notion that YOU have been convinced that there is not a god?

LMAO- “if people can be convinced there is a God”?

I knew there was a God before anyone ever told me! Convincing is something you do to someone when they don’t believe. kiddo 😉

Thanks for the heads up! 🙂

Thanks a bunch, Mike, I am now supplied with nightmare material for at least the next year or so.

Wiertz most likely did at least overdramatize whatever experience he had…but let’s just hope none of us are ever in a position to find out for ourselves.

Wow! Amazing stuff. (pardon pun: a bit ‘Heady’ if I do say so…ahem! 🙂

Again, I say, Mr. Dash, your brain is very interesting. Thanks for sharing the little nuggets of lesser-known history, however macabre. I simply wouldn’t enjoy your work any other way!

This is some seriously interesting shit.

Do I see a new volunteer?

This was really fascinating! The only part I got a little lost on was where they hypnotized people to feel what the one being executed was feeling? I mean, that’s a terrifying concept, but I can’t honestly believe they accepted that as admissible evidence.

I mean, the event where Wiertz vividly described the feelings and thoughts of the executed man is enough to make your stomach turn, but to be taken as scientific proof? I’m not so sure about that.

You’re a GREAT find!

This experiment was conducted exactly 147 years before my birth.

“Wiertz’s impressions, too, were so vivid, so melodramatic, that it hard to believe that they did not come to him as he penetrated a dying brain, but were actually generated somewhere deep within his own morbid imagination.”

you think?

Quando degolaram minha cabe? Passei mais de dois segundos Vendo meu corpo tremendo E n? sabia o que fazer Morrer, viver, morrer, viver

Translation: When they cut off my head For more than two seconds I watch my body shake And I didn’t know what to do To die, to live, to die, to live

These are the lyrics of Soulfly’s Sangue de Bairro. It’s about an outlaw rebellious gang who still from the rich ang give to the poor.When they were captured, their heads were decapitated and displayed in the square of the city of Recife, Pernambuco

Fantastic article.

tldr?

I didn’t read the entire thing, so someone correct me if I’m wrong. The article states that they experimented to see how long people are conscious after a guillotine does its work. For example, one experimented with blood transfusions and remarked the head came back alive for some time. Others claimed a head purposely blinked 20 times after execution. Some say another person looked at the executioner after. These claims are all up to debate, and aren’t passable as science. Yet, modern belief is that the head remains conscious for ~ 15 seconds due to an ultimate lack of oxygen to the brain.

Reports vary. A small number of cases show evidence of a severed head reacting to external stimuli, but only for a few seconds.

Yeah, but it’s pretty easy to come to the conclusion that no, any movement is spastic in nature and people don’t retain any consciousness after being beheaded.

Absolutely fascinating! Thankyou

While it is a subject of curiosity (I think a few seconds of consciousness are a near certainty), it’s not clear to me why people should think that the seconds of awareness after beheading should be so much more horrifying than the minutes immediately preceding it.

Now that is some food for thought.

Fascinating article

Pingback: Tweets that mention Some experiments with severed heads « A Blast From The Past -- Topsy.com

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Shirehistories (Emily Brand). Shirehistories said: Just read this. And now I feel sick. Blergh. RT @executedtoday Awesome post: Some experiments wth severed heads http://ow.ly/3KD1K […]

What an amazing read – several real `tests’ or `experiments’ that were done with the heads of those beheaded by guillotines, as well as a ton of resources to similar stories. A great detailed read of the subject matter. Bookmarked.

Giovanni Aldini did experiments on severed heads in 1802. Aldini’s goal was to make the head blink, or perform other abilities, using the voltaic pile (early version of the battery that produced 100 volts continuously) created by Alessandro Volta. Aldini demonstrated that with the voltaic pile he could shove cables into the ears, mouth, nose, and even the brain, to cause facial muscle contorsion. One researcher who was interested in Aldini’s theory of various metal having the ability to make a frog’s leg move, James Lind, was frequently visited by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley became the husband of Mary Godwin, or then, Mary Shelley, author of “The Modern Prometheus” or as it’s popularly known as “Frankenstein”.

Pingback: Some experiments with severed heads (via A Blast From The Past) « Paradigm Amalgamation: Art, History, Politics, Fashion, Culture

stumbled across this sight last night- it’s wonderful. I suspect it will hurt my GPA (sooo much procrastination material), but I just might learn more.

Lovely stuff.

Do keep it up.

Thanks a lot for your article “Some experiments with severed heads” – I printed it out immediately. As a Wiertz aficionado and a guide in his museum I was very pleased to find your description of the facts, and during my guided tours I nearly tell the same story before the triptych, from Charlotte Corday’s indignation over the “conte cruel” by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam to the experiment of Wiertz – and making a little mistake as until now I thought erroneously that the execution actually took place on the Place Saint-Géry (I live nearby) instead of at the Porte de Hal. I have also written a long ghost story around Wiertz and his most famous painting “La belle Rosine”, which has been published here in Belgium in 1998, and an outline for a “horror” play or screenplay on his

life.

After reading the article I found your address, and – happily for me – I also found out that your works are available in a French version: I’m certainly going to shop for “L’archipel des hérétiques” and “La tulipomania” here in the Brussels bookstores. Since you are interested in strange stories, I wonder if you have ever written something around the ghost of Lucida Mansi (http://tuscany.travel/en/art-history-culture/legends-and-misteries/lucida-mansi-from-lucca/ ).

I had always wondered, really.

If conscienceness was lost after 2-3 seconds, they it must be very blurry and in a sense dull after a very sharp pain procedding the first half a second, but i can only assume haha x

Pingback: S. Weasel

Pingback: Antoine Wiertz: Madness and the Maiden - The Autodidact in the Attic

Some additional evidence from The Straight Dope Message Board:

Very fine article. Have been looking for Languille by some time now – this will do nicely. The part about Wiertz was a pleasent bonus.

Yeah, i’m gonna call bullshit on this.

Anybody who’s seen a straight-up cardiac arrest (not a heart attack. Heart attacks lead to cardiac arrests) would know that it doesn’t take 15+ seconds for the person to lose consciousness. It’s boom, gone, in a second or less.

The loss of blood pressure from a beheading would all but instantly knock a person unconscious. I mean, sometimes even the slight drop in blood pressure due to standing up too quickly can make us briefly lose our balance and cognitive abilities. A complete loss of blood pressure would be an instantaneous loss of consciousness.

This story about a severed head directly responding to and looking at the person calling his name for 20-30+ seconds is bullshit. Maybe there was some twitching, but the person doesn’t have to be conscious to twitch.

Pingback: My first journal entry — July 17th, 2015 | My Journal

Once the jugular vein is severed, its only a matter of few seconds (4-7) that the Brain passes out, essentially putting the individual in unconscious state.

If the head has been severed then the head will feel pain only in the neck region as the remaining body been disconnected, that too for a few seconds.

As a teenage I pondered this question for hours. My thoughts are below.

I think the sudden loss of blood pressure would render the head unconscious within a few seconds, death occurring immediately afterwards. With some brain activity (thought nothing we would consider conscious) happening for a few minutes until oxygen levels are too low to support it.

The experience, I imagine would be something akin to the numb shock you get if you accidentally cut yourself. So I’m not sure the last few seconds of awareness would register as much pain as it would feel numb. The conscious experience might be similar to the feel one gets as you experience shock, the loss of blood pressure in the brain causes you to black out as your perception of reality become horribly distorted.

im only here because karl pilkington spoke about this years ago…its complete bollocks!

That was an interesting article. The 1905 description of Languille’s execution I can believe as being factually reported. The 1848 Brussels one with hypnotism is pretty clearly a gothic fantasy in the style people expected at the time. Poe was still alive, and the horror style with death pangs vividly described was a popular theme all over. The French, due to their experiences during the Revolution, probably knew most about it. I’d have to look it up, but I believe the beheading of either Anne Boleyn or Mary Stuart was reported as having her lips moving some little while after the act. I’ve also read that it was a practice of some executioners during the Reign of Terror to pick up the severed head, turn it so its eyes could see the body, and the face would take on a look of horror before it stopped moving.

I could only picture Eddard Stark while reading the whole answer.

Death is by no means immediate after a beheading. There was a Russian experiment conducted in the 50’s I believe. They severed the head of a dog and then connected the major veins to an oxygenation blood pump. Not only did they keep the head alive but the head was responsive until the machine was turned off. The video footage of this experiment is fairly disturbing so I will not link to it, but it is easily found on YouTube with a simple search.

It is not true that a head can be decapitated, so the name of that triptych is a con.

Decapitation means ‘taking the head away’. You cannot take the head away from a head. it is its own head. What happens to it is, it gets debodiated.

Hope this helps.

Pingback: Малки експерименти с отрязани глави | Какви ги мислят криминолозите?*

Hmmm….

Daily Telegraph of London, today’s date.

First hint of ‘life after death’ in biggest ever scientific study

“Southampton University scientists have found evidence that awareness can continue for at least several minutes after clinical death which was previously thought impossible.”

Given that in mainstream medicine it has recently come to light that many coma patients were aware of their surroundings even though unable to communicate the fact, shows that there are more levels of consciousness than accounted for by the standard presumptions of physical responsiveness and expected EEG readings.

Then there are the NDEs (Near-Death Experiences), the recent renaissance of investigation into same illustrating that even mainstream science believes the foregoing to be so, to the extent of warranting further scrutiny.

And then we have the fact that irreversible brain death is presumed to occur after four minutes of ischemia (lack of circulation/oxygen). There have been a few cases e.g. of hypothermia where the patient was ‘revived’ after much longer than that. So the brain can remain viable for much longer than “a few seconds” absent oxygenation.

Finally, we have of late some mainstream physicists postulating regarding the possibility that, as believed by many people for millennia, living things including humans may indeed have a spirit or soul, a form of consciousness or coherent energy pattern (e.g. a sort of dynamic, energetic hologram actively encoding information in Planck-scale quantum hyperspace, or the ‘Dirac Sea’), which is distinct from the physical body, is what gives life, life–and which survives the death of the body, perchance to be ‘recycled’ into a new one.

In a living person, the brain acts as a ‘quantum interpreter’ of sorts, an interface with the ‘laboratory-frame’ or physical 3-space, but the energetic body or ‘soul’ has an independent existence therefrom.

Further, these researchers have as extensions of the theory, considered it as a possible basis for parapsychological phenomena.

These physicists are seeking quantum-mechanical explanations and indeed, have alluded that the deeper one delves into the latter field, the more one comes to the inevitable conclusion that these concepts must have a basis in reality.

Some experiments and observations such as Kirlian photography and the so-called “Phantom-Limb Syndrome” of amputees (neither of which–skeptics’ misguided arguments to the contrary–have been adequately ‘debunked’), among others, also appear to illustrate the existence of an ‘energy body’ which is an exact copy of the physical (or perhaps vice versa).

Therefore it is perfectly plausible that a severed head could, even beyond the few seconds of active response to external stimuli, continue to think and perceive for a time…even to the extent of feeling its body. If there is a soul or energy-body, it would naturally still remain connected to the separated parts of the physical one, as such separation occurs only in physical space, until finally ‘leaving’ altogether. And until the latter process is complete, it would be expected to perceive both the latter, and the ‘beyond-world’, as it ‘straddled’ the two.

Also, it is furthermore quite plausible that a ‘gifted medium’ could connect to that consciousness to relay its experiences to the outside world. Quantum entanglement or “Spooky action at a distance” (with no measurable elapsed time in communication, therefore implying either superluminal propagation or a preexisting connection through hyperspace) is a well-proven concept in physics and has been considered as a possible explanatory mechanism for psychic phenomena.

It is only a natural human reaction, of course, for some to assuage their primal fear and horror at the implications by closing their minds and saying “It’s just bull”, without offering rigorous arguments or evidence to support their contention.

Science is yet a very long way from a complete understanding of the nature of life, death and consciousness–but we’re getting there, inch by inch, because for the rest of us who are open-minded, there is insatiable curiosity and fascination.

Why limit the experiments to the head of a just-deceased person? For example, if the male genital is severed from the body along with the testicles, can it achieve an erection when stimulated? Can it ejaculate once stimulated sufficiently?

If so, it then becomes possible to give hope to women who were unable to conceive by their current husbands due to the husband’s infertility. The woman could “interact” with the severed peis in such a way as to make it ejaculate while inside of her, and technically speaking, it would not be cheating because no man would be attached to it.

Rediculos you say? I say, no more rediculus than this article, which takes us all for fools.

[…] I am not an expert so I will not give you an answer. However, once upon a time I run into one rather elaborated history of answering that question. I found that article to be one of the best things I have read on Internet (in category of anything).

Maybe you will find it fascinating also. Maybe you will even find your answer […]

Pingback: Sunday sermon | ccoutreach87

Pingback: Creepy Things You Didn't Know About Getting Decapitated - Cool Dump